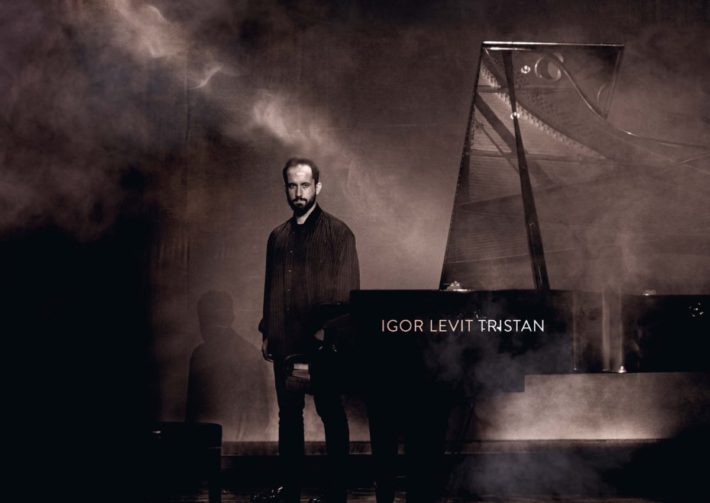

Despite traversing a different musical avenue, Igor Levit’s Tristan shares hidden connections with his 2021 behemoth On DSCH, which included Shostakovich’s complete Preludes & Fugues and Ronald Stevenson’s Passacaglia on DSCH. Both have a challenging scope of offerings and Stevenson as a commonality: his piano arrangement of the Adagio from Mahler’s unfinished 10th Symphony is featured here. With the high bar that Levit set on his previous album, one wonders with eager anticipation how much farther he can go.

A test lies in the very first work, Lizst’s universally recognized Liebestraum No. 3. While some might find his pacing on the brisker side (when we consider Kissin’s from his Carnegie debut or another lovely one by Nobuyuki Tsuji), I personally found the tempo conducive to his voice leading and shaping of the phrases. We get a performance that is contemplative and sensible yet still expressive and fluid.

Hans Werne Henze’s Tristan is a collection of works for piano, electronic tape, and orchestra – an intriguing contemporary perspective on one of the most iconic orchestral introductions written. Though it might be an acquired taste, a patient listen reveals the wide range of Henze’s colors and compositional techniques. The deep yearning of Wagner’s Prologue (fueled, of course, by the iconic “Tristan chord”) makes for a sweeping, emotionally charged experience right off the bat, but Henze’s (track 2) could not be more different. He reduces the orchestra’s presence to limited commentary, letting the piano instead take the lead. Levit captures the composer’s intended coolness: the pointillistic textures are crystalline but also tenuous in their softest moments. It is this nuanced grasp of instability that drives the work despite its sparseness.

The orchestra plays a far larger role in the Lament (track 3), where unease of the Prologue transforms into a more sinister and persuasive presence. The Gewandhausorchster brings this change to light via the woodwinds’ atmospherically eerie harmonies which really get under the skin. Meanwhile, the brass, percussion, and strings do their part to deliver a vivid and cinematic portrayal of suspense and chaos. Folly borders on insanity in the fourth movement (track 5); here, we hear the definite presence of the electronic tape that gives a somewhat disorienting (but maybe that’s the point?) but undeniably interesting perspective to the live sonorities. Despite the constant snippets and interjections, both pianist and orchestra maintain firm control throughout the performance.

Related Posts

- Review: Arc I – Orion Weiss, Piano

- Review: “Labyrinth” – David Greilsammer, Piano

- Review: Messiaen – Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus – Bertrand Chamayou, Piano

The liner notes aptly describe Stevenson arrangement’s of the Adagio from Mahler 10 as a mediating work between Wagner and Henze’s Tristans. The way Levit treats the monophonic opening (originally played by the violins) attests to this: the solitary minimalism we heard in Henze’s opening has hints of not of coolness, but now of nostalgia. What Stevenson’s transcription reveals effectively is the starkness of Mahler’s dissonances–while these are tempered by the softer timbres of the orchestra, moments like 1:50 onwards show their cutting angularity. Transcribing any part of any Mahler symphony for a singular instrument is no easy feat, and perhaps it is for this reason that a work of this magnitude should be left alone; although Levit does an admirable job, the medium itself simply doesn’t match up to the textures that a much larger ensemble can provide.

The concluding Harmonies du Soir sounds somewhat muddy with too much pedal, but it has lovely moments: the E major middle section, for instance, gives us due warmth. Even within the lyricism, the declamatory peaks speak to us clearly and serve as an effective lead-in to the conclusion.

Despite the fine bass register of the piano, less can be said about the treble that sounds plunky and stringy on occasion. Other than that, the sound engineering itself gives us a vivid surround-sound feel (especially in the Henze, where it’s much needed). Anselm Cybinski’s liner notes wisely focus on the Henze and the Stevenson, which proves a helpful guide through these less familiar works.

As with his other albums, Levit aims to challenge the listener as much as he does himself – and in so doing, lets us embark on a thematic and cathartic journey. Although there are some inconsistencies this time around, the thoughtful curation of works and performances take us on quite the exploration indeed.

Tristan

Igor Levit – Piano

Sony Classical, CD 19439943482

Recommended Comparisons

Read more classical music reviews or visit The Classic Review Amazon store

Follow Us and Comment:

[social_icons_group id=”964″]

[wd_hustle id=”HustlePostEmbed” type=”embedded”]