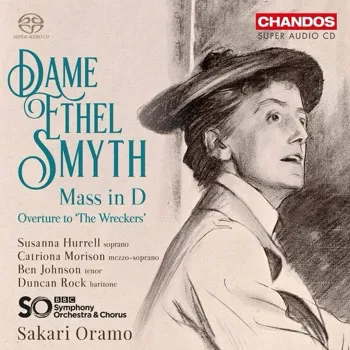

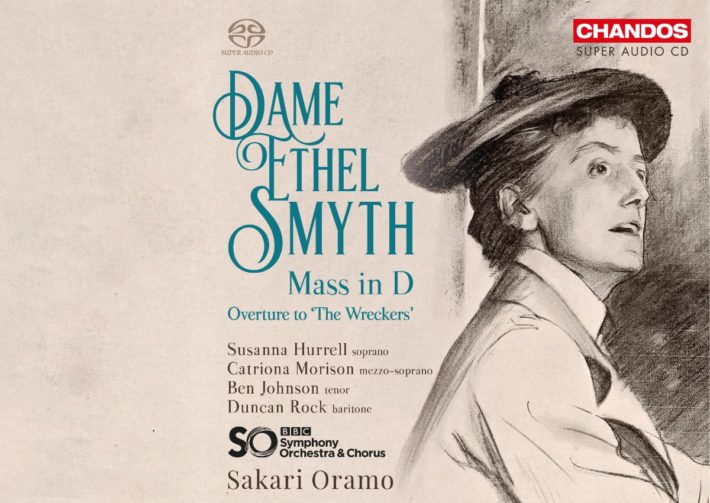

Dame Ethel Smyth is without a doubt the most well-known British female composer of her generation. “Well-known” in this context, however, is something of an oxymoron. Smyth studied in the Leipzig Conservatory alongside Dvořák, Grieg and Tchaikovsky. Private studies followed with Heinrich von Herzogenberg, who’s friends included Brahms. Smyth’s sound is distinctly Romantic; her Mass in D, composed in 1891, is heavily indebted to Brahms’ “German Requiem” with a similar scale, harmonic devices and orchestral and choral textures.

The six movements of the Mass are performed by the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, directed by Sakari Oramo, in the order Smyth suggests. Though a typical order in the liturgical tradition will have Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, Benedictus and Agnus Dei, a footnote from the composer requests the Gloria to be placed last and in doing so, it puts the most musically climactic movement appropriately at the end.

The Kyrie unfolds with grave solemnity and pathos, contrapuntal choral entries are clear, precisely directed by Oramo. There are moments akin to the Kyrie of Mozart’s Requiem, but the vibrant orchestration and rich harmony bring an unmistakably Brahmsian feel. The music surges on a number of occasions, however, with Oramo holding back so to be ready for an increase in tension in the Credo. With obvious echoes of the second movement from Brahms’ “German Requiem”, Symth’s extensive Credo takes the music from minor to major. Oramo ensures that the jubilation and excitement are measured, so that the Gloria is not overshadowed.

Capturing the reverent atmosphere in the Sanctus, containing a well-executed soprano solo by Susanna Hurrell, Oramo uses highly effective rubato to highlight the peaks of emotion, without sounding sentimental. The Agnus Dei is darker with a substantial tenor solo by Ben Johnson, which Oramo contrasts brilliantly with the choral sections, bringing out different colors. Finally, the Gloria is paced to make the most of the climaxes, saving the grandest sounds for the final bars. Oramo builds tension and resolves it with effortless ease, providing the most fitting and rousing finale to this impressive work.

The stars are the BBC Symphony Chorus, who’s enthusiasm and respect for the mass can be sensed from beginning to end. Although amateur singers, the choir has an excellent blend and balanced sound with clear diction, secure intonation and a warmth of tone. They are well-drilled, handling their parts with security. Oramo’s direction is clear, ensuring consonants are placed with accuracy throughout. The four soloists (Susanna Hurrell, Catriona Morison, Ben Johnson and Duncan Rock), who’s parts are not significant, are mostly commendable and provide moments of contrast. They use a more Italianate Latin, with some excessive vibrato on occasions, whilst the chorus’ is more Anglicised with a purer sound. Oramo’s long relationship and understanding of the strengths of both choir and orchestra brings a sense of unity and creative vision.

Opening the album is the overture to Smyth’s most famous piece, her opera “The Wreckers”. The music has elements of her peers, Stanford and Parry, and characteristics of her contemporaries, Elgar and Vaughan Williams. Oramo understands this piece’s dramatic and rhapsodic character, giving each of the many contrasting elements different colorations. This is a very stylish performance indeed, with grand swells rise and fall like the sea, building to an impressive climax.

So few of Smyth’s works have been recorded. This is only the second recording currently available of the mass and one of only a handful of “The Wreckers” overture. Whilst Helmut Wolf’s release of the mass with Württembergische Philharmonie Reutlingen and Philharmonia Chor Stuttgart is commendable for being the first, it fails to match the majestic scale or drama of Oramo’s. The choral sound lacking the same depth or clarity of diction, though Wolf’s soloists take the limelight on occasion.

Oramo’s well-balanced and engineered rendition was recorded in Watford Town Hall, London, earlier this year. The acoustics add to the color of the choral textures and the organ is finely balanced against the choir and orchestra — whose playing is superb. Chandos have commendably invested heavily here, elevating the status of Smyth’s neglected choral masterpiece, giving it the acknowledgment and recognition it deserves. A worthy SACD release which will be difficult to surpass and a welcome enhancement to any choral music library.

Dame Ethel Smyth – Mass in D, Overture to “The Wreckers”

Susanna Hurrell – Soprano

Catriona Morison – Mezzo-Soprano

Ben Johnson – Tenor

Duncan Rock – Baritone

BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus

Sakari Oramo – Conductor

Chandos, hybrid SACD CHSA 5240