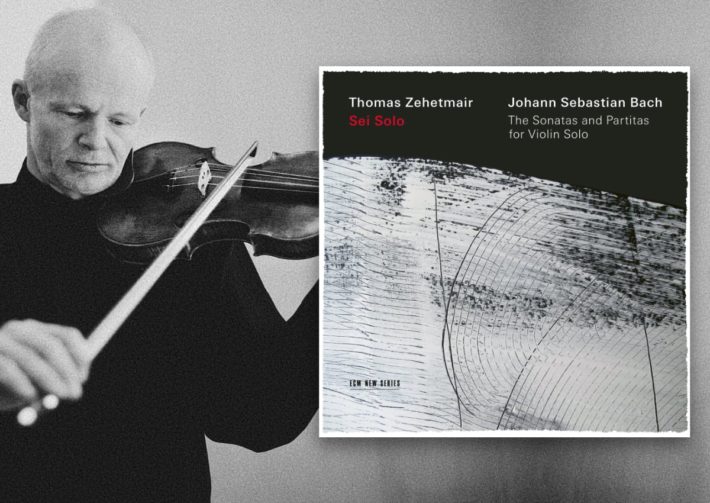

More than 35 years since his last recording of the complete sonatas and partitas by Bach, violinist Thomas Zehetmair returns to these works with a new approach, this time on period instruments, informed by years of experience. Getting beneath the surface, he finds the beauty as well as the soul of these pieces.

Zehetmair chooses to perform the sonatas on his Eberle violin of c.1750 and the partitas on an unknown violin c.1685 of South Tyrol origin (coincidently the years of Bach’s birth and death). The tone he produces from these period violins is exceptional, warmer and richer than his modern instrument rendition. His approach has mellowed overall from his earlier recording, bringing something more introspective but no less characterful. He programs alternating sonatas and partitas, the same way Christian Tetzlaff did in his 2017 recordings.

Beginning with the first sonata, Zehetmair’s approach is quicker overall than Rachel Podger (2006). The opening “adagio” is very dramatic, though Podger brings a sense of spontaneity with her broader tempo, allowing for greater rise and fall in the phrasing. The Fugue flows on naturally and with vibrancy, more angularly than Podger’s take, bringing out the toccata-like passages with crisp articulation. The quicker approach by Zehetmair in the third movement (“Siciliana”) brings out the character of the dance. The voicing in the concluding “presto” is nothing short of impressive.

In the second sonata, Zehetmair gives more space to the music than in his previous recording. The “Grave” opening movement of this sonata opens with a solemnity. His “Fugue” has similar pacing to his earlier recording, but is less angular and with a better sense of melodic line. The “Andante”, now much broader, is more reflective. The closing “Allegro” has more subtle dynamics, not black and white as previously, projecting a spectrum of color.

The second partita has a freer approach. The dances are very expressive, with a relaxed pulse, but still rhythmic, especially in the “Sarabande”. “Giga” has vibrancy and thoughtful dynamics. The “Ciaconna” starts with taught rhythmic accuracy, but as it evolves, the expressive qualities of each variation are exploited fully. Bowing is controlled, aiding the shape of the phrasing. Whilst the performance has a fluidity, it never feels lost or meandering, always preserving a purposeful direction.

The Third Partita has the same expressive approach. It maintains interest across the whole album, with an omnipresent spontaneity. The opening “Prelude” contains the excitement one may expect, but with a more pensive air, whilst Podger is more buoyant. “Loure” is more lyrical and reflective. The “Gavotte en Rondeau” is highly articulated, and Zehetmair’s understanding of all the colors of each section is evident. Podger, however, captures the spirit of the dance stronger in this movement and in the Menuets. Zehetmair’s Menuets are more free-spirited and his “Bourrée” is played as a beautiful chain of sound. The impressive “Gigue” brings a fitting uplifting end to over two hours of exceptional Bach.

The ECM booklet gives useful insight from Zehetmair on his approach and is coupled with an intensely argued essay from Peter Gülke. The recording is well-engineered and Zehetmair exploits the reverberant acoustic of Propstei St. Gerold, Austria to his advantage. In finding the spiritual and the reverberant, he brings a commanding authority, his ornaments are subtly executed throughout. Podger and Tetzlaff are in a less reverberant acoustic and recorded slightly further away, which gives their recordings a very different feel.

Throughout, Zehetmair shows faithfulness to Bach’s scores and the phrasing is natural. Ornamentations are unintrusive, and the dynamics entirely sympathetic. These are very honest and sincere interpretations; perhaps not for those who prefer their Bach more regulated, but certainly worthy of taking some time to ponder and savor.

Image: ©️ Julien Mignot

Bach – Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin

Thomas Zehetmair – Violin

ECM, CD 2551