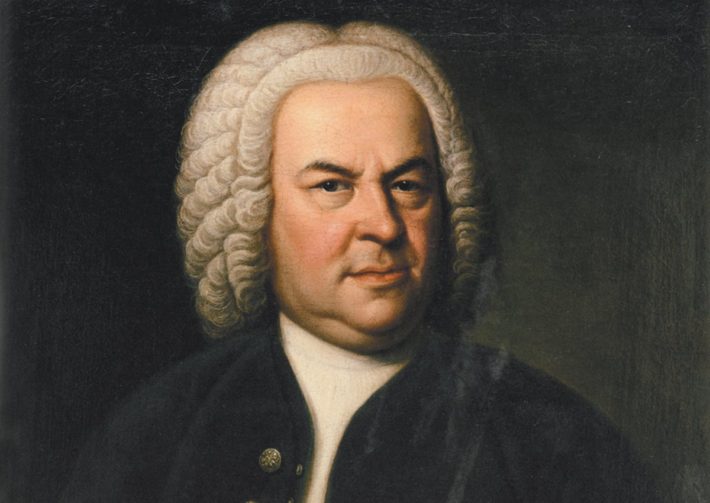

Johann Sebastian Bach was one of the few last great Baroque composers, and the most advanced and sophisticated of them all. In his long career, Bach wrote for any instrument and in any genre imaginable except opera. He was always aware of his contemporaries and predecessors, continuing to be fully inventive even in his late life.

Bach musical thinking is polyphonic – maintains several voices that are played simultaneously but remain independent. Later composers, most if not all presented on our Beginners Guides, knew and incorporated counterpoint elements in their works, but put a heavy emphasis on the relationship between melody and accompaniment, with the former receiving more weight. Bach was a practical composer in the best sense of the word; he wrote for what was necessary at the time – church music for Sunday services, instrumental works for programs at a local cafe house, and works for academic or pedagogic proposes. That is not to diminish the spirituality and emotional impact projected from his works.

During his lifetime, Bach was mainly renowned as an organist, and was often called to examine and perform on organs in nearby towns. After his death in 1750, Bach’s music went out of fashion and was only known to connoisseurs and selected musicians. There was also very little pieces that were officially published during Bach’s lifetime, one of the reasons why the small number of works that were saved from obscurity included the keyboard works like the “Well-Tempered Clavier”, Goldberg Variations and 6 partitas. In fact, it was Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach that was considered “the famous Bach” until the second half of the 19th century.

Felix Mendelssohn was the first well-known figure that revived major works by Bach – most notably the St. Matthew Passion, on a well-received Berlin concert in 1829. Since then, Bach’s music triumphantly returned to the concert and recording canon, with significant help from the recording industry, and later the historically informed movement, which promoted performing Baroque pieces on instruments and practices from the 18th century. Today there is no dispute that Bach is one of the best classical music composers ever lived. Some argue he was the greatest.

Editor’s note: As on other articles from our “Beginners Guides” series, the album recommendation for each piece are also chosen as a good starting point and a way to be introduced to the music, and not necessarily as the best recording.

Brandenburg Concertos

Bach’s 6 Brandenburg Concertos are all early works, some based on previous material but revised to perfection and considered some of the masterpieces of instrumental baroque music. The Concertos are Bach’s attempt at the Concerti Grossi form, where a group of soloists with different instruments plays against (or in dialog) with an accompanying orchestra. Each of the six concerti showcases different instruments with strings and basso continuo; for instance, a “natural” trumpet, recorder, oboe, and violin in Concerto No. 2, or violin and two recorders for the Fourth Concerto. All of the Concertos but the first contains three movements, the outer fast and the middle slow or transitional. The name “Brandenburg” is taken from the house name Brandenburg-Schwed, where Christian Ludwig, the music’s dedicatee, was Margrave. There is no proof that these Concertos were ever performed in this court during Bach’s lifetime.

Trever Pinnock was one of the pioneers in performing Baroque music on period instruments, and his early version with The English Consort from the mid-1980s still holds his own against many period performances. But his newer version with the “European Brandenburg Ensemble” is even better, and one of the best digital version currently available. The orchestra groups together some of the leading period instrumentalists and is a highly enjoyable way of getting to know the cycle – The group share their love for the music in a transparent, enthusiastic and high-spirited performance, with a clear and pleasant recording.

Those who prefer modern instruments, can turn to a classic version of the Concertos by “I Musici”, with a warm, thicker but never too heavy a rendition. The soloists include big names such as trumpet player Maurice André and oboist Heinz Holliger, and features Frans Brüggen on recorder.

Orchestral Suites

Bach other orchestral masterpieces are the Four Orchestral Suites, or “Overtures”. It’s important to note that Baroque composers considered an “orchestra” as a group of players playing different instruments, certainly not the over 100 players we today associate with large symphonic ensembles. The Suite was one of the most popular genres in orchestral writing of the Baroque era, with composers such as Telemann, Lully and others writing many dozens of such compositions. Bach wrote only four, but all exemplary. Each Suite starts with an Overture in a French style (slow, dotted-rhythm introduction followed by a quick segment), them a series of dances, such as Gavotte, Bourree, Gigue and more.

Similarly to the Brandenburg Concertos, each Suite is composed for different group of players, only there is more emphasis on the full orchestral playing than on the exchange of ideas between soloists and larger ensemble. The second suite is special in that sense – It’s built around a flute solo with strings and continuo accompaniment. The “Air” for strings from the Third Suite is one of the best-known pieces in western music.

Christopher Hogwood recorded the Four Orchestral Suites in the late Eighties, and his performances are still fresh and vibrant more than many newer versions in the catalog. Some of his tempo choices may divide opinions (the opening Overtures are rather fast), but the players of the Academy of Ancient Music sound like they have the time of their lives, and this is indeed one of the best recordings this group ever produced.

Naville Marriner released two beautiful versions of the Suites, both played by his modern-instrument Chamber orchestra, the “Academy of St. Martin in the Fields”. From his 1970s analog version and his later, 1980s digital version, the first one is preferable; While this is an older recording, it still conveys the lusciousness of this group’s strings and highlights superb performances of the woodwind section. The second version, also fine, lost some of their spontaneity of the earlier version, and the vibrato, especially in the second Suite, can be a bit much even for the die-hard lovers of romantic approach to the music.

Violin Concertos

Bach wrote several solo and double violin concertos, influenced by the popular Italian Baroque Concertos by Vivaldi, Corelli, Albinoni and others. From Bach’s surviving concertos, the two solo Violin Concertos in A Minor (BWV. 1041) and E Major (BWV. 1042), as well as the “Double Concerto” for two violins (BWV. 1043) are still in the active repertoire, and played by all major violinists.

The Violin Concertos survived in orchestral parts (not in Bach’s hand-writing) from members of “Collegium Musicum”, a group of musicians from Leipzig that met every week when the weather allowed it to play instrumental music by Bach and other composers. Most musicologists agree that although these parts are the latest surviving evidence of these Concertos, they were composers much earlier, in either Weimar or Cöthen. Many violinist and conductors change certain elements in the original manuscript, based on transcriptions for harpsichord and orchestra that Bach made for these Concertos, which include some later thoughts and changes.

Similar to the Brandenburg Concertos, the Violin Concertos are in three-movement form – the outer movement fast and lively, the slow reflective and sometimes improvisatory. The final movements are based on rhythms used in Suites such as Gigue and Rondeau. Like many late-Baroque concertos, the soloist-orchestra relationship is based on polyphony and the ability to differ important melodic lines of the soloist form that of the orchestra or continuo.

Shunsuke Sato and Il Pomo d’Oro present a weighty, sometimes reflective but always dynamic and interesting performances of the two solo and one double Violin Concertos. The accompaniment is full yet transparent, with a superb recording. Their measured way with this music, as well as the subtle and responsible deviation from the written text to add ornamentations, makes this a fantastic way of getting to know these Concertos played on original instruments, surpassing many other period performances from the past 30 years.

On modern instruments, one has to go back to Arthur Grumiaux’s superb version of the three Concertos with his recording group, “Les Solistes Romands”. This late-1970s recording ruled the catalog for many years, and presents the concertos with a flair of romanticism. The expressiveness and generous vibrato of Grumiaux needs some getting used to, especially when coming from period instruments performances, but the ears soon adjust. A must-have album for violin enthusiasts and listeners who wish to glance at “old school” Bach.

Sonatas And Partitas For Solo Violin

It’s not specifically known to whom these violin solo pieces were written for, though we know that Bach worked with many fine violinists in his years in Küten and Wiemer, and he himself was intimately familiar with the instrument. Bach wasn’t the first to write such pieces for the solo violin – Composers such as Biber and Telemann, among others, have composed such works before his – but none reached the complexity of polyphonic writing for a solo string instrument, the emotional depth nor the spiritual heights these works possess.

There are 3 Sonatas with four movements each and 3 Partitas with multiple dance movements. From the group of 6 Sonatas and Partitas, it’s best to start with the Second Partita in D minor, a pinnacle of the violin repertoire. The last movement, “Ciaccona”, is a set of variations on a single bass line, and has been transcribed for many instruments, most successfully to piano by Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924). The Third Partita contains some lovely tunes and is the most optimistic of the group. From the Sonatas, the first in G minor is moving for its chilling opening. All-in-all, the set is a must for any listener who cherishes the violin, and certainly for the aspiring violin player.

All serious violinists from the twentieth century and beyond have recorded Bach’s complete solo works, few of them several times – From a hyper (but lovely) romantic view of Perlman and Grumiax, to a more “objective” and cooler view of Shaham or Chung. Nathan Milstein, in his second version of the cycle (DG), still sounds superb in terms of musical understanding, taste and spontaneity. Some may play these works in more beautiful sound or intentional originality, but Milstein brings vast knowledge, rhythmic vitality and conviction, which still sound fresh and engaging today.

Giuliano Carmignola, in a relatively recent release, makes a good case for playing these works on gut strings and baroque bow. The sound is more intimate, more pleasant than other period performances, and there is a better projection of the dance rhythms that the Partitas are based upon. The Sonatas are played more modestly than on longer bows and stronger strings, but remain interesting and involving throughout. The famous Chaconne has a good structural projection, showing that internal strength is sometimes more powerful than an outspoken one.

Solo Cello Suites

Bach’s six Cello Suites are few of the best works ever written for cello, and are the “holy bible” of this instrument. Bach manages to add harmony and simple polyphony by the way of “hints”, making the listener “fill-in” the harmony of a single line. The Cello Suites are a bit more consistent in structure than the violin partitas: all the suites have six movements, with a Prelude, Allemande, Courante, Sarabande and a final. The fifth movement is either a Menuet, Bourree, or Gavotte. The first prelude of each Suite is often improvisatory and the Sarabande is the emotional center of the Suite.

There is some debate on the type of instrument these Suites were originally written for. Suites No. 1-4 were most likely written for a cello similar to the instrument we know today. The Fifth Suite, however, was written for a five-string instrument (the cello classically has four), and the Sixth Suite is written for a higher instrument than the original tuning of a cello, even for the time, what makes some of the “historically informed” performers to play this suite on Viola da Gamba. The Prelude of the first Cello Suite is the most famous of all (one of the most well-known pieces ever written for solo cello), but every movement of the six Suites is great music, and will bring endless joy to the beginner listener.

As in the case of the Solo Violin Sonatas and Partitas, every notable cellist has recorded the six Cello Suites at least once. For listeners that come to this great music for the first time, Yo-Yo Ma’s recent and third attempt at the six Suite is a delightful introduction. Ma’s way with the Suite is clear-headed, clear and well-articulated, especially in the fast dance movements. Other cellists have injected more emotional involvement and spirituality into their performances (Fournier and Rostropovich, to name just two), but Ma’s deep understanding and conviction are never in doubt. Superb recording quality too.

After years of experimentations, recent years have shown few superb versions of the six Cello Suites played on period instruments, with gut strings and Baroque bows. David Watkin’s 2015 version is truly impressive from first note to last, showing a depth of feeling, and a vast knowledge that never becomes didactic.

Keyboard Partitas

Bach’s six Keyboard Partitas are essentially Suites with preludes and dance movements written for harpsichord. They were published individually in the 1720s but eventually published as Bach’s Op. 1 in 1731, titled “Clavier-Übung”. The six Partitas are more demanding than Bach’s earlier sets of six Suites, the English and French Suites. It required abilities that far exceeded those of the amateur pianist of the day (most movements still do), not only in a technical sense, but in their compositional complexity and diversity of mood and style. The first Partita in B major is the most familiar and often played from the cycle, but the cycle as a whole forms a lovely recital, each Partita is a masterpiece that brings its own set of qualities.

Igor Levit’s full cycle for Sony is ravishing, allowing listeners to hear the complexity of Bach’s keyboard writing, expertly projecting a sense of style and reflection. There are warmer or more playful accounts out there on a modern piano (Perahia and Schiff are good examples), but this is the set to go by as a starting point, to be cherished even after owning other successful versions.

A beginner listener who wishes to experience the six Partitas played on a harpsichord can listen without hesitation to Trevor Pinnock’s version on Haenssler, his second version on record. Pinnock plays a strong, double-keyboard harpsichord and his style is direct, with only a small amount of ornaments that never feel over the top. The resonant recording somewhat compensates for the natural harshness of the harpsichord.

Goldberg Variations

Bach’s Goldberg Variations is one of the longest, most difficult and profound set of theme and variations in the history of music. According to Bach’s first biographer, Forkel, the piece was written to a certain Count Kaiserling, a Russian diplomat who used the services of a young and talented harpsichordist, Johann Gottlieb Goldberg. The harpsichordist was asked to play to the count when the latter suffered from insomnia, and when receiving an invitation to compose the piece, Bach thought a series of variations on a theme will have a soothing effect on the sleepless count. This legend is highly disputed by Bach’s scholars (Goldberg was 14 at the time of the piece’s composition), but it gave the variations their nickname.

The Goldberg Variations are based on a wonderful theme, an “aria” found in Anna Magdalena’s notebook (Bach’s second wife). The theme is followed by 30 variations, every third variation being a Cannon. The Cannons themselves are based on a growing interval (starting from a unison, then a second, third, etc). Many of Bach’s scholars and performers have pointed out additional patterns in the 30 variations, as styles (Kirkpatrick), grouping by mood (Perahia), and more. In any case, there is no doubt that Bach invested all of his talent and abilities, whether compositional, stylistic, or technical when producing the set. The variations close with a repeat of the original Aria, making the journey come to a close in a full circle.

As pointed out in The Classic Review’s “best of” guide to the Goldberg Variations, Murray Perahia is the go-to piano version to a beginner or veteran listener: “not only is it one of the best versions of the Goldberg ever recorded, but also one of Perahia’s best and a landmark piano recording. It’s that good. It should be in any respectable classical music collection.”

On harpsichord, Richard Egarr on Harmonia Mundi plays the set as if a life experience is incorporated in his playing, without losing any of the freshness and sense of awe from this major piece of art.

For choosing the best recordings of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, see our three-part guide here.

Organ Works

Bach played many instruments expertly according to testimonies, but the organ was “his” instrument. The irony is that the work most associated with Bach’s organ repertoire – The “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor” – is one of the most debated among his entire works; Scholars differ on its date of composition or whether it is a transcription from another instrument. In any case, it takes the average listener about a second to recognize, and one can’t argue its magnificent use of all aspects of this grandest of instruments. Other famous works for organ by Bach include the “Passacaglia” in C Minor, the “Prelude-Fantasy and Fugue in G Minor”, “Toccata Adagio and Fugue in C Major” and many “Chorale Preludes”.

Recommending a recorded version Bach’s organ music to a beginner listener is a perfect example of the difference between the “most overall recommendation” to a “starting point” recommendation, for listeners who wish to approach a classical music piece for the first time. Peter Hurford recorded the complete Bach organ works for Decca in the 1970s, using different instruments in churches all around the world. His set was noteworthy for its surprising clarity, letting listeners hear the complex polyphony of the separate keyboards and pedal. Up until then, most performances emphasized Bach’s “Grandeur”, a tendency which often tainted many other performances of Bach’s music in general. This “Double Decca” set includes all the famous works and best Chorale Preludes. Hurford is not the most exciting organ player, nor is he the most technically impressive – Yet there is no better way to get to know and appreciate Bach’s organ pieces, and that’s a highly enjoyable journey indeed.

Cantatas

There is no other composer that is more associated with the term “Cantata” than J.S.Bach, though again, he is far from the first to excel in the field. Bach wrote Cantatas all of his professional life, but it took significant time and effort from his side when he held the position of Cantor in Leipzig (1723-1750). He was required to write a choral setting for church service on Sundays, with texts based on scriptures, German poems, or crowd chorales. A typical Bach Cantata is written for a chorus, which sings the opening movement and a closing chorale, and two arias with recitatives for soloists, accompanied by an orchestra with continuo, including an organ. Ever the inventor, Bach diversified the Cantatas, and many of them diverge from this typical structure; some include concerto-like movements, others are built around a theme which requires an almost operatic participant from soloists, while some Cantatas are particularly intimate and quiet, requiring only a handful of musicians. Bach completed three full-year cycles of Cantatas, and composed dozens more for separate occasions, including secular. Out of the hundreds of Cantatas Bach believed to have composed, about a third is lost. The Cantatas that are most-often-heard today are No. 4, 21, 51, 56, 140, 147, and 202, among others.

With such a wide-ranging cycle, it’s difficult to choose only a few Cantatas, not to mention recordings. Some conductors recorded all the Cantatas, others thought that few famous ones suffice. Masaaki Suzuki’s cool, precise clean cycle is considered one of the best, though some critics were ambivalent about Suzuki’s “idealistic” view of the music. Although supremely performed and recorded with a state-of-the-art SACD technology, other versions were less “clinical” but showed more human warmth and vulnerability. Nonetheless, the single release that included two famous Cantatas, BWV 147 and 21, can be purchased without hesitation, and the clarity allows to be better equated with the music.

On modern-day instruments, at least as of the 1960s and 1970s, Carl Richter was a good representer. His tempi seem slow today, and although he used chamber-sized orchestra, the strings give an over-romantic view of the music. The soloists are often too operatic for the Baroque style. Yet there are many good examples of Bach performance style that was somewhat lost after the period-instrument groups took hold of the catalog. Richter’s double album groups together all the famous cantatas he recorded for Deutsche Grammophon, and includes big names like Edith Mathis, Maria Stader, Peter Schreier, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and others.

Mass in B Minor

Bach’s Massive Mass in B Minor is a work of roughly 25 years. Bach originally wrote the first two chapters – Kyrie and Gloria – after the death of the Elector of Saxony, and in hope of obtaining the title of “Electoral Saxon Court Composer” from his successor. In the last few years of Bach’s life, he added to these two chapters three more – Credo, Sanctus, and Osanna, the latter includes Benedictus, Agnus Dei, and Dona Nobis Pacem. Each of the chapters includes several movements for soloists, extended choir, and a large orchestra, and some of the movements are borrowed from material previously used in Cantatas and other choral works. After joining the chapters to form a complete Mass, and with the exception of the Matthäus Passion, this is the longest and most ambitious of Bach’s choral works. After the reworking in the 1740s, the Mass in B Minor is remarkable for its diversity of styles and techniques, and can be seen as an exemplary work of Bach’s choral compositional abilities.

Philippe Herreweghe’s third recording of the Mass in B Minor is his best, and a good way to experience Bach’s great Mass and Herreweghe’s unique style for the first time. One of the pioneers of the Period Instruments movement, Herreweghe’s style looks back to influences from the medieval and early baroque, together with late German Baroque influences.

Performances of the B Minor Mass on modern instruments were unfortunate in the current catalog. The best performances – Neville Marriner and Peter Schreier’s wonderful versions (both on “Phillips”) – are hard to come by and are in a desperate need of re-issue (both are available on streaming services). Karajan and Klemperer’s versions are a safe enough bet if you want to know the Mass on modern instruments, but the heaviness and disregard of choral phrasing make them somewhat problematic.

This concludes our beginners guide to Bach. Visit our Beginners Guides to classical music page and get to know more classical music composers. Sign up to our newsletter to get updated on new guides when they are published.

Albums included with an Apple Music subscription:

Latest Classical Music Posts

- Review: Brahms – Late Piano Music – Piotr Anderszewski

- Review: Mendelssohn, Enescu – Octets – Quatuor Ébène, Belcea Quartet

- Review: Rachmaninoff – Piano Concerto No. 3, Tchaikovsky – Nutcracker Suite – Nobuyuki Tsujii

- Review: Brahms – Symphonies Nos. 2 & 4 – Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, Edward Gardner

- 5 Best Loudspeakers For Classical Music – 2026

- Review: Schubert – 4 Hands Piano Music – Bertrand Chamayou, Leif Ove Andsnes

Follow Us and Comment:

[social_icons_group id=”964″]

[wd_hustle id=”HustlePostEmbed” type=”embedded”]