This is the final release in the Nelsons and Gewandhausorchester Bruckner symphony cycle. While the Gewandhaus lacks the exalted Bruckner pedigree of their Amsterdam, Berlin, and Viennese colleagues, this is their third complete cycle. The first, made in the 1970s under music director Kurt Masur, is plainspoken and under-characterized, especially when compared to the recordings by Karajan and Jochum released concurrently. The second cycle, conducted by Herbert Blomstedt, was released in super-audio sound by the German label Querstand about a decade ago. This series includes several excellent performances, but (at least in America) it is difficult to track these recordings down. In this latest series, the orchestra sounds perhaps even finer than it did under Blomstedt, and DG’s engineering is exceptional, offering a wide dynamic range with an ideal balance of clarity and warmth.

Each of the recordings has included works from Wagner’s operas, and this program opens with the “Prelude and Liebestod” from Tristan und Isolde. Beautifully played, but emotionally unsatisfying, the desperate longing that permeates performances led by Furtwängler, Karajan and Tennstedt is experienced only intermittently here. The same is true of the Liebestod, though I should admit that I prefer performances with soprano. The playing of the Gewandhaus is gorgeously ripe but turn to Karajan’s last recording with the Vienna Philharmonic and Jessye Norman and one is suddenly transported to a different plane.

In an earlier review of these same forces performing the second and eighth symphonies, I claimed that Nelson’s reading of the earlier symphony was more fully successful: the same is true of this new release. Symphony No. 1 was the first symphony Bruckner felt worthy of a number (and public performance); in his later years he remained fond of it, referring to it as his “saucy minx.” There are, of course, multiple editions currently available: two Linz (1877) editions, one each by Haas and Nowak, and the 1891 Vienna edition by Brosche, published in 1980. The last is the version used here.

Nelsons’ tempo choices throughout the first seem perfect, and he encourages a wide dynamic range and clear articulation. The orchestra has an impressive ‘Brucknerian’ sound, built from the bottom up, with burnished brass, characterful yet blended woodwinds, and richly upholstered strings. Yet Nelsons often employs a wider variety of color and weight from the orchestra, allowing more light and shade than is heard in Barenboim’s Teutonic Berlin Philharmonic performance. Schaller’s recording with the Philharmonie Festival Orchestra on Profil is similar in conception, but the engineered sound is very bright, so that some climaxes are overly brash.

Related Posts

- Review: Bruckner – Symphony No. 2 – Vienna Philharmonic, Thielemann

- Review: Beethoven – Complete Symphonies – Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra – Nelsons

- Review: Lise Davidsen – Beethoven, Verdi, Wagner

Claudio Abbado was a strong proponent of the work, recording it several times during his career. The first, released in 1969 by Decca, features the Vienna Philharmonic, as does his second studio recording, released in 1996 by DG. Both use the Linz/Haas edition. But his final recording, with stupendous playing by the Lucerne Festival Orchestra, uses the 1891 Vienna edition, and much like Karajan’s last Bruckner records, it features an expert sense of architecture wedded to an incandescent sense of the music’s dramatic sweep. Nelsons’ reading may not reach this same exalted level, but it is in the same league.

Competition is far fiercer with the fifth symphony. The Gewandhaus players cover themselves in glory: woodwind solos are beautifully realized, and their sound at full cry is weighty and fulsome. Attention to dynamics and articulation remains impressive, and rarely have I heard the final movement’s dense polyphony clarified so well. Many performance get bogged down trying in this continuous counterpoint, but Nelsons’ sets his course and keeps the music moving – I never found my attention wandering. And the scherzo has plenty of character and wit. But in the slow movement Nelsons does love the music and the gorgeous sound of his players too much, resulting in a loss of focus and sense of the music’s architecture. Günter Wand once argued that a successful performance of any Bruckner symphony requires a complete grasp and control of its architecture. The truth of that assertion is apparent in his final reading with the Berlin Philharmonic (RCA/Sony) or Abbado’s riveting reading with his Lucerne orchestra (only available on a Accentus Music DVD).

The last point is arguably subjective. While some find the music’s architecture key to experiencing Brucker’s emotional and spiritual truth, others find this approach distancing. Certainly, the energy and power of this reading (the arrival at the final chorale in the Coda has tremendous impact), and the remarkable playing of the orchestra is consistently thrilling. Readers who know and collect Bruckner will know which interpretive approaches they prefer; any newcomer to Bruckner will find much to savor and enjoy in these performances.

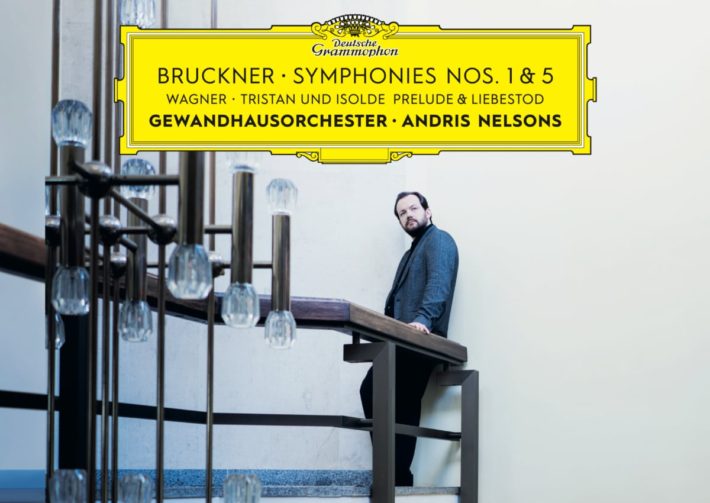

Bruckner – Symphonies Nos. 1 & 5

Wagner – Tristan und Isolde

Gewandhausorchester Leipzig

Andris Nelsons – Conductor

Deutsche Grammophon, CD 4862083

Recommended Comparisons

Read more classical music reviews or visit The Classic Review Amazon store

Follow Us and Comment:

[social_icons_group id=”964″]

[wd_hustle id=”HustlePostEmbed” type=”embedded”]