Mozart’s seventeenth piano concerto was written for his gifted student Barbara Ployer, who performed the work on June 13, 1784. However, the work was probably premiered by Mozart several weeks before at the Kärntnertor Theater for an audience that included the Emperor. In 1784, Mozart was at the height of his popularity: in March alone, he played thirteen concerts in Vienna, followed by another four in April. Surely, he hoped this new work would continue that success, and it is easy to see why it would: Concerto No. 17 (K.453) perfectly balances Joie-de-vivre and melancholy, inspired melodies and virtuosic writing, in a classic example of Mozart’s genius.

Any new recording of this work (and of Concerto No. 24) enters a crowded and tremendously competitive field. And the performance of the opening movement in this new recording does raise a few red flags. The orchestra plays in a historically informed style, yet the string section seems too large to manage the lightness required in this movement (for that, listen to Alfred Brendel in his late digital recording, accompanied by the Scottish Chamber Orchestra under Mackerras). Moreover, Shaham’s playing is overly cautious: by ensuring every dot and dash in the music are correctly realized, she and the orchestra makes the music too serious and studied. Her cadenza shortchanges the feeling of spontaneity that Brendel, among others, brings to his performance.

Something however changes in the second movement: orchestra and soloist are now fully attuned to the music’s melancholic atmosphere. The flute and oboe solos are touchingly rendered and Shaham’s playing evokes the music’s forlorn sadness. There is tenderness in the dialogues between orchestra and piano, while Shaham’s playing at 4’12”, as well as in the cadenza, are simply ravishing. The final movement returns to the light and playful mood of the first, and all the players seem to be enjoying themselves much more.

Desperate Atmosphere

The joyful banter of the seventeenth concerto is quickly forgotten once the stormier and desperate atmosphere of Concerto No. 24 (K.491) begins. Featuring the largest orchestra Mozart ever used in a concerto (adding clarinets, trumpets and drums to the more usual flute, oboes, bassoons and horns), it is one of only two piano concerti in a minor key. Many musicologists have described the concerto as “sounding more like a work from the Romantic period;” indeed, Beethoven, after hearing a performance of the concerto, purportedly said to his friend Johann Cramer, “we shall never be able to do anything like that!”.

The tumultuous opening is thrillingly rendered by the orchestra and Shaham’s playing throughout the movement is thrillingly expressive, the music’s despair and anxiety fully communicated, most especially in the cadenza. The second movement brings a completely different character, described by musicologist Alfred Einstein as “the purest and most moving tranquility, and (…) transcendent simplicity of expression.” The wind writing is particularly expansive, and the St. Louis winds players relish their opportunity by offering especially colorful playing.

The third movement brings a return of the tense mood of the first movement. Mozart writes a theme with eight variations, featuring several difficult 16th-note runs that Shaham dispatches with deceptive ease (in the liner notes she discusses how difficult this is to achieve). Each variation is full of character, a sure sign that these players are intently listening and playing off of one another like chamber musicians. The final variation shifts into compound meter but remains in the minor, ending the work in an unsettled gloomy mode.

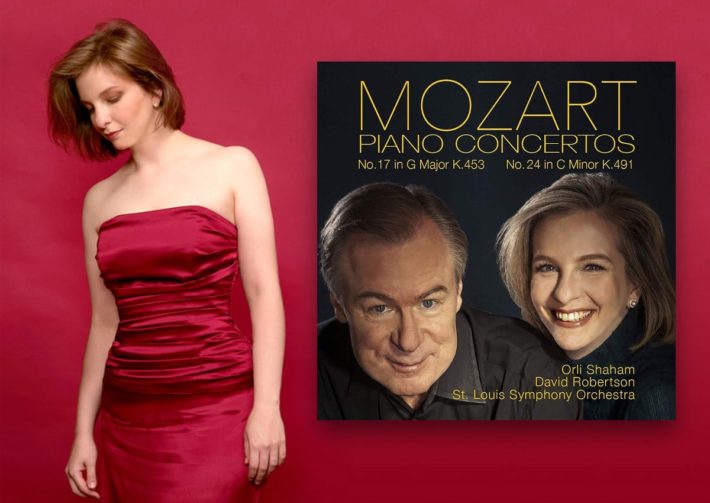

The St. Louis Symphony was once one of the most recorded American orchestras and it is good to hear them again and in such fine form. Shaham is an exceptionally fine pianist, well partnered by David Robertson. These performances are beautifully caught by the sound engineers, with a realistic balance between orchestra and piano. Even in a tremendously competitive field, these are performances that are well worth hearing.

Mozart – Piano Concertos No. 17, K. 453 & No. 24, K. 491

Orli Shaham – Piano

St. Louis Symphony Orchestra

David Robertson – Conductor

Canary Classics, CD CC18