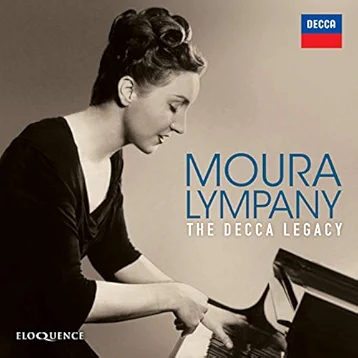

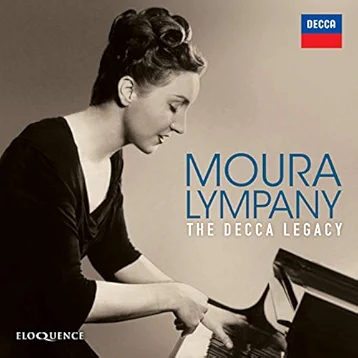

Mary Gertrude Johnstone, known by her stage name of Moura Lympany, made her debut with Mendelssohn’s First Piano Concerto aged 12 in 1928. Leaving an imposing recorded legacy of just a small proportion of her vast repertoire, she made a speciality of Eastern Europian music — notably Rachmaninov, Prokofiev and Khachaturian. English composers of her generation featured substantially too, including Richard Arnell and Alan Rawsthorne. This latest release, titled “Moura Lympany – The Decca Legacy”, collates her Decca recordings from 1941 to 1952, compiling vintage piano recordings with previously unreleased material. The recording dates reveal how rapidly Lympany recorded, a testament to her boundless energy and natural talents.

Recording Rachmaninov’s complete Preludes is quite an undertaking, especially when the composer himself had not done so in his own lifetime, making Lympany’s first recording (1941) a colossal achievement. Lympany’s second attempt was made in 1951, and a further version for Erato followed in 1994. Both Decca versions are included here, revealing her impressive technique and beautiful sound. The second, 1952 performance is the finer version, with fewer blemishes, more sophisticated phrasing and refined use of rubato. The sound on both is remarkable, due to transfers and remastering that capture the performances well. The 1952 performance has some hiss (though considerably less than the 1941 set), but the commanding interpretative strength shines through convincingly, and one soon forgets the extra noise, being drawn-in completely by Lympany’s artistry and communicative prowess.

Lympany’s Rachmaninov Third Piano Concerto contains cuts sanctioned by the composer. Being one of the first women to record this work is remarkable in itself, not to mention her fine account. Lympany’s recording of the Schumann piano concerto has unconventional tempo choices, with the first two movements on the quick side. Lympany was taught by Mathilde Verne — a pupil of Clara Schumann, and insisted that these paces were authentic to Schumann’s vision. In the first two movements, Lympany’s balance between the hands is remarkable, along with exquisite phrasing. The quicker speed here is persuasive, evoking a very different character — less reflective but more characterful. Grieg’s Piano Concerto follows, in which Lympany’s decadent sense of musical flamboyancy is distinguishable, despite the distance sound and noticeable hiss.

Lympany’s two Decca recordings of Saint-Saëns’ Second Piano Concerto reveal her nimble dexterity, ensuring the second and third movements sound effortless, with an intoxicating sense of fun. A live recording made at the first night of the Proms in 1943 (available on Somm) reveals a commendably consistent approach. This live performance (though without the second movement, which has been lost) is by far the most impressive for its exuberant excitement. Khachaturian’s Piano Concerto was given its European premiere by Lympany, and her two versions are comparable here, both with the same conductor — Anatole Fistoulari. The later 1952 version benefits from Lympany’s work with the composer and cleaner sound. Rawsthorne’s First Piano Concerto became a piece she had a great affinity with. Her 1945 recording is marginally brisker than her more famed and insightful EMI version from 1956.

Chopin featured significantly in Lympany’s repertoire, but she wasn’t particularly renowned for her interpretations of pieces by the composer. Perhaps ahead of her time, she believed in keeping the pulse steady, using rubato only in the right-hand. Lympany’s complete sets of Preludes, Nocturnes and Waltzes are available on other labels, but here we have the first release of a 1947 recording of the Third Piano Sonata.

The sound quality of this intriguing release is disappointing, but the interpretation is fresh and communicative, especially in the inner movements. Another previously unreleased recording is Samuel Barber’s Piano Sonata (Op. 26). A remarkable piece that showcases Lympany’s virtuosity with an evocative performance, despite occasional inaccuracies and poor recording quality.

Lympany is represented at her interpretative best in this retrospective, even though there are performance blemishes. Recorded in mono, this welcomed reissue reveals a snapshot of one of the twentieth century’s most remarkable pianists, with almost 8 hours of recordings to sample and enjoy.

Moura Lympany – The Decca Legacy

Moura Lympany – Piano

Decca Classics / ELOQUENCE, CD 4829404