Image: ©️ Dario Ocasta

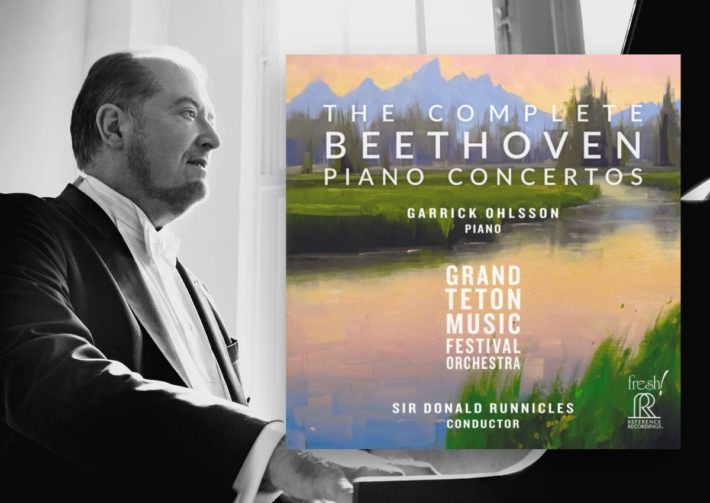

Garrick Ohlsson aptly describes performing the complete Beethoven piano concertos on concerts that were held between 5th and 9th of July last year as ‘heady’ – but a decades long relationship with these works makes him a perfect candidate for this ambitious project. He finds a familiar collaborator in Sir Donald Runnicles, who as Music Director of the annual Grand Teton Music Festival, has brought together orchestral musicians from across 90 ensembles.

The C Major Concerto sets a promising bar indeed with excellent balance and integrated sound. The opening section wafts in charmingly before expanding into a tutti of pomp and circumstance. As voluminous as the ensemble sounds, Runnicles and the players don’t ignore the finer points: for instance, every note of the recurring scalar motif is mindfully present. Ohlsson enters in a breezy, nonchalant fashion, almost as a reminder to enjoy the movement’s levity. He maintains this ease of character throughout the movement but also gives the faster notes a little extra sparkle.

The middle movement, however, is a different story: the pianist’s lyricism is on full display via supple lines that are as reflective as they are expressive. An egregious, unevenly regulated instrument (which unfortunately proves very bothersome throughout all the concerti) still does little to take away from the artistry itself. The final movement returns to the sense of fun with both soloist and ensemble delivering bustling, infectious energy.

The C minor Concerto takes on a more austere persona. This performance, however, still adds touches of elegance reminiscent of a Mozartean Sturm und Drang style; we hear them in the orchestral opening’s gently punctuated staccatos or in the lightness of Ohlsson’s fingerwork at 4’09”. Emotional balance is achieved, though, in the grander moments—the performers don’t shy away from a robust forte or assertive dynamic shift.

As for the slow movement, if the opening solo of Concerto No. 1 is contemplative, then its counterpart here becomes even more introspective: Ohlsson’s pianos are more subtle but the result more captivating. While an interpretation like Krystian Zimerman’s (with Bernstein/Vienna Philharmonic) is profound in its own right, Ohlsson’s proves deeply personal. Meanwhile, the ensemble does well to add richness, dimension and body to the movement.

Related Classical Music Reviews

- Review: Beethoven – The Five Piano Concertos – Haochen Zhang, Nathalie Stutzmann

- Review: Beethoven – Complete Piano Concertos – Zimerman, LSO, Rattle

- Review: Beethoven – Complete Violin Sonatas – Midori, Thibaudet

The opening chord of Beethoven’s 4th Concerto is arguably one of the most nerve wracking things to play in a live performance: not only does the voicing have to be immaculate, but the timing has to be on point. While Ohlsson’s is finely voiced, it’s a hair too short. The “hang time” for the audience to appreciate the resonance isn’t there like it is in Brendel’s (with Rattle/Vienna Philharmonic). Unfortunately, the same abrupt cutoff happens with the ascending scale just moments later. The ensemble does help make a nice subsequent recovery, though: its interlude has perceptible layers of textures from the rustling accompaniment to the persuasive repeated note motifs that effectively build volume and momentum.

In the slow movement, the interchanges between the forces are contrastive enough throughout but feel somewhat at odds: while Ohlsson takes the time here to create thoughtful phrases, the orchestra sounds rather brusque. The Rondo, however, sees everyone on the same page where vibrant energy is concerned. The clarity of the soloist’s trills and turns adds a pleasing airiness to his passages.

As for the ‘Emperor’ Concerto, Ohlsson takes what feels like a matter-of-fact approach to what should be a more commanding opening. In this regard, Arrau with Sir Colin Davis/Staatskapelle Dresden proves much more satisfying where emphasis of crucial phrases points are concerned. One would hope that the recapitulation of this section fares better but the oomph of orchestral arrival is not there and the piano’s rolling arpeggios are rushed.

The middle movement is fine with the exception of the obviously early pizzicato downbeat–but still no match for landmark recordings like the 1979 Michelangeli/Giulini account which is truly transcendent and moving.

The pianist’s own foreword might be the most succinct part of the multi-part liner notes. Scott Foglesong’s musical commentary is grounded more in historical context than technical musical analysis; we also get interesting insights from Runnicles in his writing. What’s rather unusual (and something I wish more notes would do) is a short essay from producer Vic Muenzer on the recording process. Things get a bit technical at times but we can understand that production is as detailed, thoughtful, and critical as the actual performance itself.

With the exception of the latter two concerti, Ohlsson and Runnicles do a solid job that captures the spirit of early and middle period concerti. These performances are what make this set worth a thoughtful listen.

Beethoven – The 5 Piano Concertos

Garrick Ohlsson – Piano

Grand Teton Music Festival Orchestra

Sir Donald Runnicles – Conductor

Reference Recordings, CD FR-751SACD

Recommended Comparisons

Zimerman & Bernstein | Brendel & Rattle | Arrau & Davis | Michelangeli & Giulini

Read more classical music reviews or visit The Classic Review Amazon store

Follow Us and Comment:

[social_icons_group id=”964″]

[wd_hustle id=”HustlePostEmbed” type=”embedded”]