Eric Lu impressed in his recent win at the prestigious Leeds Piano competition, playing in the final round Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.4, released later on Warner Classics. Lu’s earlier participation in the Chopin Competition (2015) was less sensational, earning him the respectful fifth spot (the first prize went to Seong-Jin Cho and the second to Charles Richard-Hamelin). This album, containing the complete Preludes Op.28, might suggest that the jury members of that competition somewhat overlooked this particular pianist. (editor’s note: this review was written in 2020, before Lu’s win in the 2025 competition).

There were quite a few distinguished accounts of the complete preludes in the past decade or so, some of them mentioned below. It’s certainly a cycle not to be taken lightly, and the best of pianists struggle to persuade when playing it in full. For one, every short prelude has its own character and style, while the pianist is also required to see the forest from the trees, providing a united whole. Lu’s unifying quality is his overall style of playing Chopin: atmospheric, rich in sonority and sensitivity of sound. He pulls the listener almost effortlessly – his dreamy, much-peddled opening serves this approach well, and the first 8 preludes almost melt into one another, never losing their contrasting character. This is also helped by the recording quality, taken at the celebrated Teldex Studio in Berlin, which allows for an impressive wash of sound and dynamic range.

I was less convinced, however, by prelude No.9, which seems to be taken more hushed than usual to fit the overall mood. This unique delicacy can work as a double-edged award – fascinating, yes, but would you always like to hear your Chopin played like that? Luckily Lu brings things back to life on the difficult G Sharp Minor Prelude (No. 12), where the pianist shows a superb balance between the two hands – listen how the bass, quick chords and melodic line all have their own voice, while projected as a full, almost orchestral piece. A remarkable pianism if there ever was one.

Another quality worth noting is Lu’s appreciation for restraint. This is evident with the slow, quiet preludes – hear how No. 13 cries out without any big gestures or superficial dynamic manipulations. The same can be said for the famous “Raindrop” prelude (No. 15), which shows great tone coloring and a flowing, unintrusive rubato, though I sometimes wanted the tempo to be quicker in the main theme (this was my main reservation from the otherwise superb Ingrid Fliter version from 2014). The soft preludes continue to hang in the air in anticipation, proving that Chopin knew what he was doing when forgoing a Fuge or a Suite to follow a prelude, as his beloved Bach did.

Lu can be virtuosic too when called for – as in No. 16 and 24. His right hand clear and even, without turning into an etude. His bass, a challenging element in Chopin’s writing, is given special treatment throughout, Lu uses it as a rhythmic anchor, as a tool to bring out overtones from the chords and melody of the right hand, and to help paint deeper colors. I also liked Lu’s ability to “speak” the phrase when appropriate, as in the unisons of prelude No.18.

Some might wish for more open, dramatic or brilliant Preludes, and from cycles in the past decade, many can fit the bill – from the solid Fliter already mentioned to the Brilliant Dong Hyek Lim, the spontaneous Nelson Goerner to the full-hearted and romantic Lugansky and Tharaud. All superb performances on their own right. This new cycle may sit comfortably next to another successful version – that of Cristian Budu from 2016, which found similar delicacy and inwardness in Chopin’s tumultuous cycle. I will also go back to personal favorites from the distant past and present, Cortot (both his 1926 and 1933 cycles), Lympany, Moravec, Pires and others, but this new cycle gives a different outlook of the preludes, which many will want to return to.

The album continues with Brahms’ first piece form his three Op. 117 Intermezzi, played with measured tempo and fascinating intricacies of tonal changes when moving between registers, though here there is a tendency to go heavy on the sustaining pedal, depriving Brahms of needed clarity. Lu’s way with the 19th-century romanticism doesn’t work as well with Schumann’s last piece for piano, the “Ghost Variations” (“Geistervariationen”, 1854). The mysteriousness and reflective mood were better left to speak for themselves, as appear on the page, instead of caressing the theme to the point of suffocation. Lu’s sound is as impressive as in his Chopin, but Schumann’s textures resist his way with the pedal and attempt at voice-leading. Turn to András Schiff of Imogen Cooper and you’ll get a clearer sense of Schumann’s ghostly ideas. This album is worth purchasing for the Chopin Preludes alone.

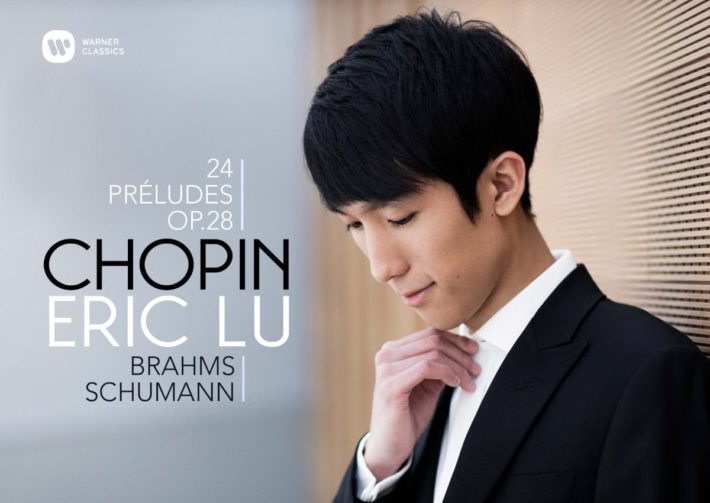

Chopin – 24 Preludes, Op. 24

Brahms – Intermezzo in E flat major, Op. 117 No. 1

Schumann – Geistervariationen, WoO 24

Eric Lu – Piano

Warner Classics, CD 9029529234