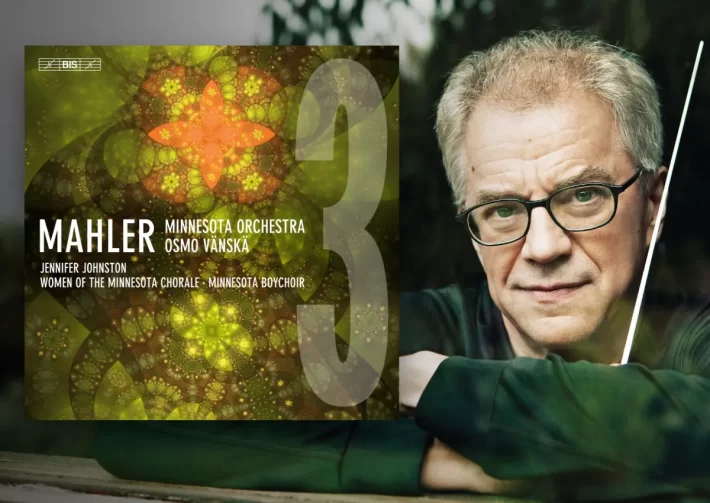

This is the final release in the Vänskä-Minnesota Mahler Symphony cycle. I have reviewed four previous entries: an excellently played first that was emotionally uninvolving; impressively committed readings of Nos. 7 and 10 (in Cooke’s performing version); and an emotionally flat performance of the ninth. These pages also saw reviews of Symphony No. 4 and Symphony No. 2.

Read our coverage of Osmo Vänskä’s Mahler albums here

A consistent strength of the series is BIS’s SACD engineering, with the latest two releases incorporating Adobe’s Dolby Atmos technology. The wide soundstage has warmth and stunning transparency; I have never heard more detail from these scores, especially listening to the Super Audio layer.

As the series progressed, the Minnesotans developed an utterly convincing Mahlerian sound. Woodwind solos have been striking and characterful, and the same holds in this performance. If space permitted, I would list every first chair, but I was particularly touched by the bassoon and oboe work, and R. Douglas Wright’s trombone solo in the first movement is excellent. The string’s unanimity of attack and tone is matched by a brass section that can roar but is even more impressive in soft playing, especially the horns.

Vänskä, as always, solicits the widest range of dynamics, while ensuring beautifully balanced orchestral textures. But in the first movement of the Symphony, the focus on detail might obscure the broader emotional arc of the music – Perhaps further exploration of the work’s spiritual and emotional core could elevate the interpretation.

Writing to his friend, Natalie Bauer-Lechner, Mahler described the first movement: “It has almost ceased to be music; it is hardly anything but sounds of nature…Mahler’s description gives us a small sense of what this music must convey – creation at a primal level. While the opening horn introduction is promising (and listen to the physical presence and clarity of the bass drum that follows), Vänskä sets a slow pace for the first theme in which clarity is prioritized over atmosphere. The brooding eeriness combined with clarity one experiences with Tennstedt (in his live LPO performance/ICA), in Haitink’s last recording with the BRSO (BR Klassik) or in Iván Fischer with his Budapest Festival Orchestra on Channel Classics) – is barely present. All three conjure a far more compelling atmosphere.

The gentler second theme (6’05”) is more affecting, yet anytime the music approaches wildness, Vänskä seems to temper it. In his excellent liner notes, Jeremy Barham tells us that Mahler wrote descriptors of the first movement throughout the manuscript: the development section (The Mob!’) moves into ‘The Battle Begins!’ (where Mahler layers themes on top of one another, creating a wild Ivesian frenzy). But Vänskä just keeps reigning in his players, uncomfortable with any such frenzy.

The inner movements are far more successful, offering the right character and sound, and deft management of Mahler’s many tempo modifications. One example of many: at 15’10” in the third movement, after the exquisite Posthorn solos (played by Manny Laureano), the otherworldly atmosphere is particularly moving, suggesting a full connection with nature, making the terrible brass chord of the Coda more spine-tingling, as if Nature has suddenly turned against us. Note too, that Vänskä honors Mahler’s instruction not to rush (nicht eilen) the final bars.

Join The Classical Newsletter

Get weekly updates from The Classic Review delivered straight to your inbox.

Jennifer Johnston’s singing in the fourth movement is deeply affecting, in part because of her care over diction. We hear every detail of the accompaniment, horns and solo violin covering themselves in glory. The fifth movement is a bit soft-grained, with less sparkle in the choral sound, but the women of the Minnesota Chorale acquit themselves well, and there is an ideal balance between voices and orchestra.

The tempo for the final movement is daringly slow (slower than any of the recordings referenced above), yet it never feels slow, because the playing is so gently luxuriant. The careful shaping of various lines shows how the various sections of the orchestra listen to each other. While it is an undeniably beautiful reading, there is again an emotional reticence that can keep listeners at a distance. Turn to Tennstedt or Fischer, let alone Abbado’s Berlin performance (DG), to experience a deeply emotional catharsis.

Like most cycles, there are stronger and weaker entries. Audiophiles will find the quality of BIS’ SACD engineering self-recommending – none of the other cycles recorded in Super Audio are superior to these recordings. Those who find Bernstein and Tennstedt too overwrought may have a greater appreciation for Vänskä’s interpretations than I do. It is undoubtedly a high point in the recording history of this orchestra, celebrating the end of a long and celebrated Music Directorship. BIS has already released a boxed set of the symphonies, 11 CDs in total.

Image: Marie Mazzucco

Recommended Comparisons

Abbado | Haitink | Tennstedt | Fischer

Mahler – Symphony No. 3

Jennifer Johnston – Mezzo soprano

Women of the Minnesota Chorale

Minnesota Boychoir

Minnesota Orchestra

Osmo Vänskä – Conductor

Check offers of this album on Amazon Music.

Album Details |

|

|---|---|

| Album name | Mahler – Symphony No. 3 |

| Label | BIS |

| Catalogue No. | BIS-2486 |

| Amazon Music link | Stream here |

| Apple Music link | Stream here |