In the long text that conductor Philipp von Steinaecker writes for this album’s booklet, he argues passionately for the use of “period instruments”, even for a work that was first premiered on 1912. but many points fail to convince. For instance, he quotes Mahler, who argued for getting a soft sound not from instruments that play it easily, but from those that require effort, strain, even exceeding their limits.

Steinecker then writes that playing is much easier to modern instruments, and that effects the risk-taking in performance, or lack thereof. That may be the case, but we have several recorded performances in which the conductor/performers play with the effort, strain, and overexertion Mahler expected. This is surely more an issue of interpretation, rather than the instrument itself.

Steinaecker also contends orchestra players at the time (strings especially) used a minimal amount of vibrato, instead using other expressive devices like portamento (sliding between notes). Mengelberg’s Mahler recordings confirm the use of portamento, but not avoidance of vibrato. There are audio interviews of New York Philharmonic musicians who played under Mahler, in which they state he often asked for more vibrato. Historic Mahler recordings by Oskar Fried and Dimitri Mitropoulos use vibrato. And surely Steinecker studied the January 16, 1938, live premiere recording of the ninth, played by the Vienna Philharmonic under Mahler’s long-time assistant and friend, Bruno Walter, in which vibrato is used throughout. If minimal vibrato is so integral to Mahler’s intentions, surely Walter and Otto Klemperer would have insisted on it in their recorded interpretations.

These contentious points would matter less if the performance itself was revelatory. But it is not. I would argue that is because this reading is content to let the instruments and techniques themselves make the music happen as if the interpretive ideas of the conductor and players are secondary.

The Mahler Academy Orchestra’s use of portamento in the opening minutes of the Symphony is effective and strange. But the first moments of angst (track 1, 2’14”) are too careful and underpowered. The same is true of the following Andante comodo – everything is in its place, but there is never the sense of raging desperation heard in Bernstein’s many readings. The flute playing is touching in track 3, in part because of its more delicate color. But the next climax (track 4, 1’30”) again lacks heft and emotional connection. This is even more notable at the movement’s central climax (track 6, 1’15”) where the trombones, in a raging fury, should pin us to the wall, as they do in Bernstein’s Concertgebouw reading (DG) or Karajan’s live performance. Here, they are merely loud and far less threatening.

The inner movements are more successful, the hues of the instruments making up for, at least in part, overly sedate interpretations. One hears a wealth of woodwind detail (the same is true of Klemperer’s 1967 with the Philharmonia, and Vänskä’s recent recording (BIS). The same careful playing neuters the terrors of the Rondo-Burleske, especially compared to the first Walter/Vienna recording.

Join The Classical Newsletter

Get weekly updates from The Classic Review delivered straight to your inbox.

Steinaecker might argue that the purity of the vibrato-less strings heard at the beginning of the final movement adds to the music’s emotional power. It is beautiful but conveys an entirely different mood, of calm solace instead of bruised, world-weary pain. Passages of sparse counterpoint have greater fragility, but the more brutal moments lack the force and weight this music must have. The movement’s horrifying climax (track 25, 0’54”) is plenty loud but emotionally hollow, the string cries that follow are precise without ever suggesting the stabbing agony experienced in Karajan’s incomparable reading.

I dislike being so negative about a performance and wondered if reading the zealous assertions in the notes first biased my listening. Nevertheless, despite repeated listening, this recording and its premise leave me cold.

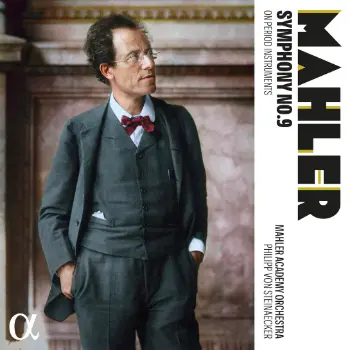

Mahler – Symphony No. 9

Mahler Academy Orchestra (on period instruments)

Philipp von Steinaecker – Conductor

Check offers of this album on Amazon Music.

Album Details |

|

|---|---|

| Album name | Mahler – Symphony No. 9 |

| Label | Alpha Classics / Outhere |

| Catalogue No. | ALPHA1057 |

| Amazon Music link | Stream here |

| Apple Music link | Stream here |