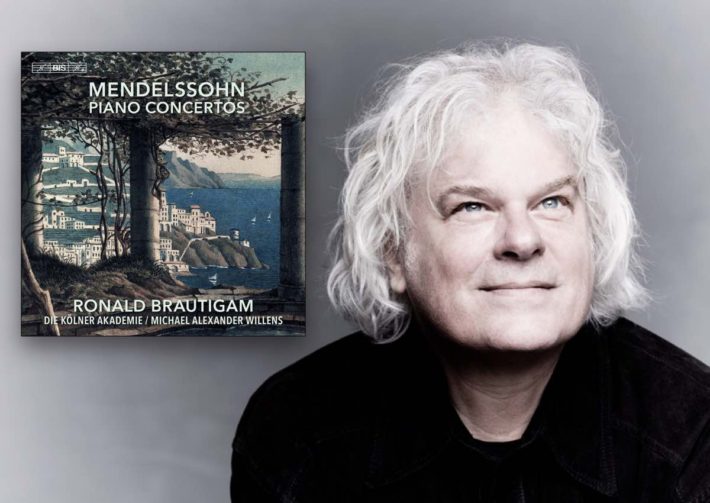

This is the second traversal of the Mendelssohn Piano Concertos by Ronald Brautigam. His first version, released in 1995 and on the same label, was performed on a modern piano with chamber orchestra (the then “new” Amsterdam Sinfonietta). This time around, Brautigam continues his Mendelssohn cycle in recent years, playing the same copy of an Erard grand from 1831, manufactured approximately when the first Piano Concerto was premiered. His partners, like in his period Mozart concerto cycle, is ”Die Kölner Akademie” group under conductor Michael Alexander Willens. Similarly to his 2 albums of the Songs Without Words and the Cello Sonatas album, it’s a revelatory listening, which requires both performers and listeners some adjustment.

The more obvious change in this version is the balance, where despite the period ensemble, with its relatively modest size and more limited dynamic capabilities, the piano timbre and sound quality will invite a more attentive listening experience. The more impressive demonstration of the period balance is best exemplified in the Dionysian-Apollonian dialogues, such as in the G Minor first movement’s 4:55. The slow movement in the same concerto is brisker this time, and it’s fascinating hearing the violas and cellos worm segment at the beginning of this touching movement played vibrato-less and phrased to suit the baroque bows and gut strings. Some will find this sound cold, others, like this listener have, refreshingly direct. The last movement, maybe due to the capabilities of the piano and well-spaced acoustics, is a tad slower. This is where the modern piano has the edge, as the quick keyboard figurations are less discernible on the Erard copy.

The Second Piano Concerto is a less brilliant piece, from piano writing and compositional standpoint, but here Brautigam and the Kölner group give a good case for it. The orchestra parts sound more punchy and the contrapunct more pronounced, as well as the differentiation between the themes in the first movement. The strongest movement in this often overlooked piece is the second Adagio, essentially a song without words with accompaniment. Brautigam was wonderful in his 1995 take of this movement, and here he is no less moving. Interestingly, the pace is almost identical in the two versions, but the new one flows more lightly, again due to the small, no-fuss violin playing and the quicker decay of the piano. Even the harmonic inventiveness at the midway of this movement (2:00) somehow sounds more daring.

Generous Supplements

The 1995 album contained an early Piano Concerto in A Minor, written in the composer’s youth. This time around there is generous supplements in the form of 3 mature pieces for piano and orchestra. Admittingly, none of these works are the most inspiring Mendelssohn, all heavily influenced by other composers of the time who wrote concertante piano works in the single movement form, with a broad introduction and sparkling, virtuosic writing. The Capriccio Brillant, Op. 22 is given a nice performance indeed, and the group tries their best at the somewhat unmemorable Rondo Brillant Op. 29. But the real revelation, and one of the highlights of this album, is the rarely performed Serenade and Allegro Giojoso, Op. 43. Composed in 1838 (close to the famous Violin Concerto), it has the hallmark of the late Mendelssohn, with an irresistible slow introduction here. It’s a welcome addition to a handful of recorded versions.

This album is a nice addition to the growing number of performances from the 19th century played on period instruments. Should listeners want to live with this version alone? Probably not. The best versions of the concertos are still, among others, Murray Perahia’s dedicated account with Academy Of St. Martin In The Fields under Neville Marriner, for their naturalness and totality of their partnership. Howard Shelley’s impressive version, conducting the London Mozart Players from the keyboard, is another, digital contender. Brautigam’s first version still sounds marvelous, but this newcomer is a fascinating, engaging album that brings a lot to the table on a heavily crowded catalog.

Mendelssohn – Piano Concertos No. 1&2, Rondo Brillant Op. 29, Capriccio Brillant Op. 22, Serenade And Allegro Giojoso Op. 43

Ronald Brautigam – Piano

Die Kölner Akademie

Michael Alexander Willens – Conductor

BIS Records, SACD Hybrid, BIS-2264