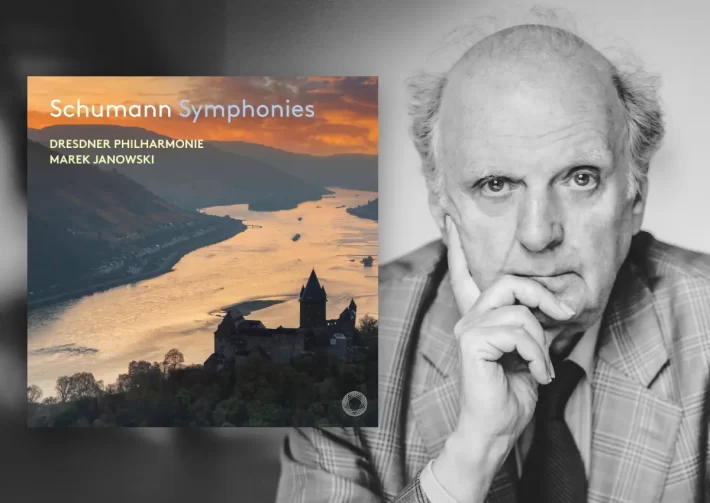

Marek Janowski’s extensive Pentatone catalogue includes the complete symphonies of Beethoven, Brahms, and Bruckner, as well as operas by Beethoven, Puccini, Verdi, Weber, and Wagner. Owning several of his recordings and having reviewed two of the opera releases (Fidelio and Der Freischütz), I would assert Janowski’s interpretations tend towards dependable rather than inspired. He respects the score, honoring its tempo, dynamic and articulation markings. He often sets bracing tempos for fast movements, and rarely dawdles in slow ones. Orchestras play well under him, and listeners can count on carefully considered orchestral balance and contrapuntal clarity, two qualities particularly important in the Schumann symphonies.

Check offers of this album on Amazon.

I was initially disappointed in the reading of the first symphony. I found the first movement’s opening brass fanfare tepid, and the Allegro lacking in fire. But after consulting the score, I realized that in the fanfare Janowski is honoring Schumann’s forte marking, whereas other conductors often override it. And with repeated listening I came to appreciate the conversational interplay between strings and winds in the development. Those of us drawn to historically informed performances may find the rounded warm string sound rather unvarying, but it is undeniably beautiful.

The Larghetto is somewhat plain spoken, its emotional temperature lower than in the Luisi (Orfeo) and Bernstein (Vienna/DG) recordings, though it heats up with the sweetly sung cello line at 1’44”. The Scherzo has greater intensity, though the Trios could have a more marked contrast in mood. The Finale is best because Janowski relaxes control over the proceedings, giving the interaction between strings and winds (beginning at 4’56”) an attractive freedom and playfulness. The Coda, driven hard, brings a brusque but powerful conclusion.

The second symphony’s slow introduction is carefully shaped, building to a powerful climax. The tempo for the Allegro is ideal, but the music’s emotional progression is downplayed. Schumann was severely depressed while composing this work, and those struggles can be heard in the Development, as the melodic motive slowly disintegrates, and harmonic stability is threatened. The obsessively repeating figure that leads into the emotional climax (starting 8’30”) should blow out ever more loudly, but Janowski never allows it to disrupt his focus on contrapuntal clarity. In Bernstein’s reading the same passage is an emotional storm.

My listening notes for the Scherzo included the phrase “Everything in moderation.” The playing is first rate, but again I would like more contrast in the Trios (the second more varied than the first). Some will appreciate Janowski’s refusal to speed up the Coda (most conductors do, though it is not marked in the score).

The slow movement is some of Schumann’s most sublime music, and with Sawallisch and Bernstein, the listener emotionally spent. Again, Janowski is more moderate, with dynamic contrasts minimized. his use of rubato sparing. The Finale should bring the same sense of victory over adversity one experiences in Beethoven’s fifth, but that is not the case here.

The third symphony is altogether more successful. The impressive opening movement has heft and energy. The Scherzo is slower than expected but unfolds with a naturalness that captures the music’s spirit, abetted by characterful woodwind playing. After a charming third movement, the fourth movement has a potent sense of atmosphere – noble and mysterious – followed by a colorful and rousing final movement.

The success of the third makes the fourth’s performance more frustrating. On YouTube one can watch Karajan rehearsing the Vienna Symphony in this symphony’s opening, spending a significant amount of time on color, articulation, and weight of sound to draw out the music’s dark, anxious mood. Janowski apparently sees the music far differently: I know of no other performance in which that angst is so minimized. And in the following Vivace, despite some excellent playing, the consistently rounded attack tempers the angularity of the melodic and harmonic writing. This is, at least in part, because of Janowski’s preference for woodwinds over brass, which makes the string and wind interactions less combative, more lighthearted. Some may find this more convincing, but I found it to be a willful reimagining of Schumann’s intentions.

The Romanze and Scherzo fare better (with particularly gentle playing in the Trios), but the final movement lacks bite and dramatic impetus, again minimizing the darker colors and moods of what is arguably Schumann’s stormiest symphony.

Pentatone’s engineering is exceptional, creating a wide and deep soundstage of warmth and clarity (and it’s also available on Dolby Atmos technology, for those who listen on Apple AirPods). The resulting transparency allows us to hear and enjoy the inner lines and disproves, once again, criticisms of Schumann’s opaque orchestration. Jorg Peter Urbach’s notes on the music are excellent.

While this would not be my first choice for a Schumann symphony cycle, there is much to admire, and for those who find the interpretive approach of Bernstein and Luisi too subjective, this new release may be just the ticket.

Image Marek Janowski ©️ Felix Broede

Schumann Symphonies – Recommended Comparisons

Bernstein | Sawallisch | Barenboim | Kubelik

Check offers of this album on Amazon.

Album Details |

|

|---|---|

| Album name | Schumann – Symphonies |

| Artist | Marek Janowski |

| Artist | Dresdner Philharmonie |

| Label | Pentatone |

| Catalogue No. | 5186989 |

| Works | Schumann – Symphonies No. 1-4 |

| Amazon link | Stream here |

| Apple Music link | Stream here |

Included with an Apple Music subscription:

Latest Classical Music Posts

Read more classical music reviews or visit The Classic Review Amazon store