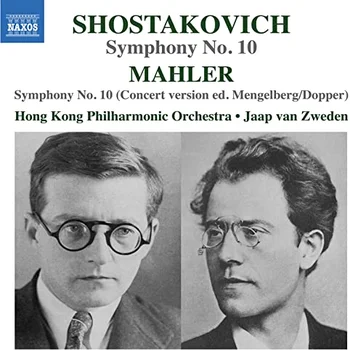

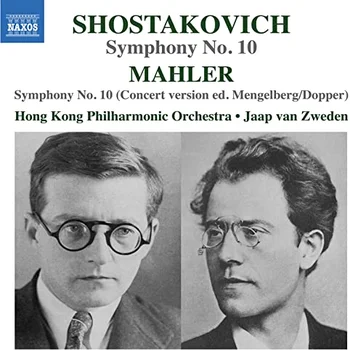

Jaap van Zweden’s reputation as a conductor largely rests on his work with Romantic era repertoire, including a Bruckner cycle with the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra (Challenge Records) and Wagner’s Ring, recorded with this same orchestra, also on Naxos. One of the consistent strengths of that set is the playing of the Hong Kong Philharmonic – the same is true here.

The program opens with the rarely heard Mengelberg/Dopper edition (movements 1 and 3 only) of Mahler‘s unfinished tenth symphony. In 1924, Alma Mahler asked composer Ernst Krenek to make a fair copy of these two movements; she then sent the copy to Willem Mengelberg, who, assisted by Dutch composer Cornelis Dopper, created a performing version. This version has an enlarged orchestration with numerous expression and tempo changes that listeners accustomed to the standard critical edition by Erwin Ratz, or Deryck Cooke’s completion, will certainly notice. The greatest difference is increased use of percussion, especially in the timpani writing. Its initial entrance at 5’48” is disconcerting (the Ratz edition has no timpani at this moment, and Cooke uses it more sparingly, without any roll). One can argue that Mengelberg, one of Mahler’s staunchest champions, would know what Mahler would have wanted, but even after repeated listening, the writing never really convinces. Note too, the unexpected gong stroke at 8’07”.

What is undeniable is the excellence of the Hong Kong Philharmonic, who play with a richly burnished sound, the strings in particular offering a wide variety of color, weight, and articulation. Each phrase is carefully shaped, and Zweden encourages lyricism from his strings, and rounded, warm sound from the brass. And this is where doubts began to creep in. The huge orchestral outburst at 18’10” has plenty of volume and weight, but it doesn’t snarl enough – the brass need to bray more. At 19’02” as the harshly dissonant chord continually builds, the first trumpet enters with a high note of such a clear ringing tone that the music’s terror is somewhat mollified. And earlier in the same movement (roughly 9’10”) where the music returns to the nature sound world on the earlier symphonies, the Hong Kong woodwinds are reticent to create any sound that suggests slithery creatures moving in the dark, whereas in the recent Vänskä/Minnesota recording, or the Rattle/Berlin recording, nature’s creepiness is on full display. The same holds true in the brief Purgatorio, which in this performance sounds more like paradise, such is the loveliness and warmth of the playing, whereas in Dausgaard’s Seattle recording the same music has a visceral hallucinogenic quality.

The Shostakovich has similar issues. The first movement has an inexorable drive that clearly communicates fearful anxiety and overwhelming tension. Zweden builds masterfully to each climax without ever letting the energy sag. The string playing is again particularly impressive, woodwinds are more characterful, and Shostakovich’s dense orchestral textures are balanced with tremendous care (sample the passage beginning at 10’10”).

The Scherzo, though, is too slow (4’35”) and tame compared to readings by Jarvi/SNO/Chandos (4’05”), Petrenko/RLPO/Naxos (4’07”), Karajan/Berlin/DG (2nd reading: 4’16”) and Nelsons/BSO/DG (4’20”). It is less an issue of speed than Zweden’s unwillingness to convey the maniacal terror of this music. Instead he seems to want us to appreciate how well the orchestra plays when we should be drawn into the music’s desperately intense emotions.

The sardonic wit and playful sarcasm of the third movement Allegretto is fully conveyed. But the final movement is again performed in a way that nullifies the music’s intent. The opening Andante is again beautifully played, low strings husky and dark, answered by the woodwind’s mournful laments. But the following Allegro is simply too slow. At 8’26” the tam-tam led climax fells the music’s protagonist, and in the subsequent measures, as the composer’s motto (D-Eb-C-B) is intoned by the brass, there should be greater fragility, as if the protagonist has barely survived. Here it all sounds too comfortable and confident. Finally, that final climax (12’34”) where the composer’s motto blares out over the rest of the orchestra, we should hear a mix of conflicting emotions: joy and rage, relief and fury. But Zweden seems incapable, or unwilling, to capture those conflicting emotional states.

The performance were recorded live in excellent sound, and the notes by Stephen Johnson are short but informative. There is much to appreciate here, and I am glad to have heard the Mengelberg/Dopper version of the Mahler. But the emotional complexities of both composers are better served in elsewhere.

Recommended Comparisons

Dausgaard | Rattle | Karajan | Petrenko

Mahler Symphony No. 10 & Shostakovich Symphony No. 10

Hong Kong Philharmonic

Jaap van Zweden – Conductor

Naxos, 8574372