Håkan Hardenberger’s repertoire is extensive. He’s recorded Baroque concertos with the Academy of St. Martin’s, modern French works with only an organ as accompaniment, and devastatingly difficult solos by Berio. Yet in these three concertos, each wonderful, each a bit odd, Hardenberger often seems lost. He is never out of his depth in technical terms, but he can’t quite find the variety of expression demanded by these modern works.

“Histoires vraies” is an intriguing collection of, in composer Betsy Jolas’ words, “sounds we try not to hear.” In the piece, Jolas strings together sparsely orchestrated ideas, some restless, some violent, all percussive. Hardenberger is joined in the soloist slot by pianist Roger Muraro, and the two together seem to be characters moving through the soundscape. Muraro’s grace notes and dissonances are sharp-tongued and attention-grabbing, and fit nicely within the scenes. Hardenberger’s lines, on the other hand, often fail to match the orchestra’s timbre. For instance, at the beginning of the piece (circa 1’00”), when the orchestra is mysterioso, Hardenberger sounds confident and sure of himself, his tone full. It happens again at 10’00” — the orchestra seems anxious, with fits of notes and sharp dynamic shifts, yet no tension is detectable in Hardenberger’s sound. There are nonetheless exciting moments, like the spots of sharp, bright tone at 2’10”, or the accelerando of notes at the very end, which contrast with the quieter and more tense moments. Despite being recorded from far away, the Malmö players’ reproductions of Jolas’ sounds come through faithfully, from the introductory concert-hall scene and something seemingly private from 4’00” to 5’00”, to the quasi-chase scene at 17’00” replete with footsteps, ending with a gunshot.

Sally Beamish’s concerto is more formally constructed than Jolas’. Each movement centres on an interval or intervals, e.g. the perfect fourth in the first movement, and there is thematic material to be shared amongst orchestra and soloist. The music is wonderful, and the National Youth Orchestra of Scotland gives an impressive reading. In the first movement, Hardenberger again can’t quite meet the challenge. In the prelude, with its epic and tectonic depiction of a sunrise, he plays with less sheen and warmth than he is capable of, and ends up feeling detached from the orchestra; in the following allegro, he plays clinically. Accurately, sure, but lacking in spontaneity or excitement. The second movement is more successful, as he seems to paint jazzy graffiti over canvases of static thirds and fourths in the orchestra. In the third movement, which studies ugliness and decay (it features scrapped cars and scaffolding pipes in the percussion section), Hardenberger can’t bring himself to play with an ugly or strident tone, or use overly accented articulations, and the result feels contradictory.

The kaleidoscopic collection of musical fragments that make up Olga Neuwirth’s “…miramondo multiplo…” pose a challenge for Hardenberger, Malmö, and conductor Martyn Brabbins. The piece is more unflinchingly post-modern than the Jolas or the Beamish, with purposefully kitschy quotes from “Send in the Clowns” and Mahler’s 5th in a movement about memory, and a few more from Handel and Stravinsky. It also discards tonality more completely. To this reviewer, the parts didn’t quite add up to a whole. Part of the issue may fall with Brabbins — there doesn’t seem to be an interpretation in place. The music moves itself forward without the feeling of artistic intent. There are other issues, too. The orchestral winds, clarinets and oboes especially, struggle with high and fast passages, sounding rather anaemic at times (2’10”, track 5, or again at 3’00”, track 7). Hardenberger gives some good performances, especially in the first and last movements, feeding off the orchestra’s energy, but his reading of the quotes in the second and fourth movements are nothing special (tracks 6, 8).

This album is a nice recording of three modern, striking trumpet concertos that falls short of being outstanding. Recommended for contemporary music aficionados, the album is nonetheless hampered by sub-par recording of the live performances of the Jolas and Neuwirth’s pieces, artistically challenging repertoire, and by Hardenberger’s reluctance to stray from his polished tone.

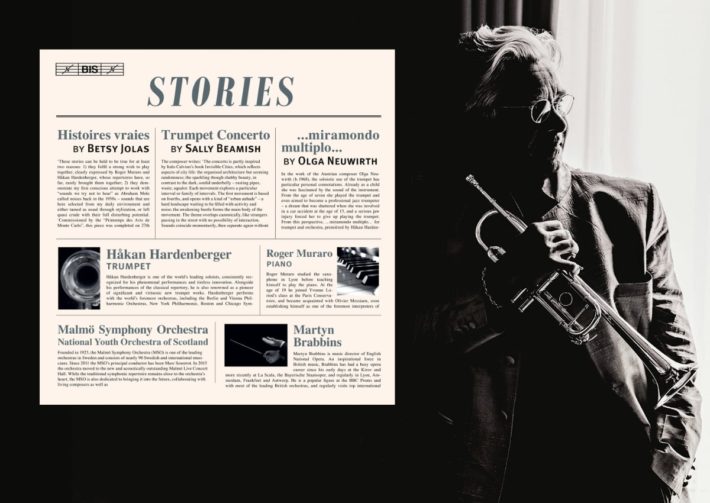

“Stories”

Betsy Jolas: “Histoires vraies” (1)

Sally Beamish – Trumpet Concerto (2)

Olga Neuwirth – “…miramondo multiplo…” for Trumpet and Orchestra (3)

Håkan Hardenberger – Trumpet

Malmö Symphony Orchestra (1,3)

National Youth Orchestra of Scotland (2)

Martyn Brabbins – Conductor

BIS Records, hybrid SACD BIS-2293