Daniel Lozakovich’s new recording of Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto and other music arranged for violin requires significant commentary. The violinist is accompanied by Vladimir Spivakov and the National Philharmonic Orchestra of Russia. Spivakov, it seems from the liner notes, has been something of a mentor to Lozakovich, Enabling the soloist to give his first major concert ten years ago, and certainly continued to mentor him. Spivakov is an accomplished violinist himself, and Lozakovich notes that since his childhood, he “was influenced by [Spivakov’s] beautiful interpretation” of Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto. Comparing the two soloists in this Concerto is an interesting exercise that reveals quite a bit about the players and the music (From the several Spivakov versions, this review will refer to the early one from 1977, made with the Slovak Philharmonic under Košler).

Lozakovich performance of the Concerto’s opening is excellent. He plays the main theme with conviction, yet maintains a delicate touch. He deftly shifts sound worlds at the “ben sostenuto” marking (2’:10”). Up to that point, his interpretation is spotless, and on par with Spivakov’s own. Beginning in the quick arpeggios, though, one starts to hear cracks. Lozakovich struggles with the pulse in this section — various bars start in different tempi, and then when he finds a good one, it becomes too metronomic. Spivakov in 1977 and others play with the tempo here, too, but they do so in a consistent way. Listen to how Spivakov the violinist returns to the same tempo after each pause. The same thing can be heard in another recent Deutsche Grammophon version of the Tchaikovsky concerto, played by Nemanja Radulovic, reviewed in these pages. Radulovic has mastered rubato, his tempo changing from frozen to blazing in instants without any disruption to the listening experience.

Lozakovich’s interpretation of the second theme feels underdeveloped — or perhaps overdeveloped. As Daniel Barenboim has pointed out, with complex pieces of music, one must take a strategic approach. In his version as a soloist, Spivakov’s approach is to push forward through the opening statement of the theme, creating urgency, and then to pull back at the height of the phrase (the high G natural). Radulovic’s approach is to first play isolated, single-bar phrases, which are emotionally devastating, and only later to allow the phrase to grow in length and meaning. Lozakovich’s approach is fairly typical and less effective; he intersperses rubato throughout the statements, and plays multi-bar phrases each time. In the end, the whole second theme fails to develop any meaning as it goes because it’s oversaturated, strategically underdeveloped due to emotional overdevelopment. He plays the theme beautifully, but afterward the listener is no richer than when it began.

The same sort of analysis could be done on the Canzonetta, the haunting second movement of the concerto. Spivakov begins simply, takes the listener on a journey, and upon returning to the theme, plays it as a reminiscence, and the listener reminisces with him. Lozakovich, on the other hand, switches things around and begins with the reminiscence, losing the listener’s attention; when he returns to the theme, it just feels like a variation.

Moving on from analyzing the music’s emotional content, there remains plenty to praise in this album. Lozakovich is a virtuoso violinist, turning in a spectacular cadenza in the concerto’s first movement (listen to those shiny harmonics!). His playing in the finale is fine-tuned and precise, yet fun. In the second half of the album, he shines most in the Méditation of “Souvenir d’un lieu cher,” (track 8), again showing off his rich tone and vibrato. His heart is clearly on his sleeve for this piece. In the two Waltzes (tracks 7 & 10), His performance is well executed, but suffers from the same issues as in the Concerto: the slow waltz needs a stronger sense of pulse, and the fast one needs more contrast.

The National Philharmonic plays wonderfully across the album under Spivakov’s direction. The strings are full-bodied, ethereal or forceful depending on the moment. The first oboe and clarinet deserve special mention for their gorgeous tone and often spotlight-stealing solo moments. The recording quality is up to DG standards, capturing the full depth of the orchestral sound without sacrificing any details of Lozakovich’s playing.

This album is highly recommended in contrast with Spivakov’s earlier recording of the concerto with the Slovak Philharmonic. The recording of the latter has an annoying, high-pitched resonance that must be willfully ignored, but the comparison is worth the trouble. On its own, Lozakovich’s Romantic debut ranks as a success but not an instant classic. He has plenty more music to record, which we can all look forward to.

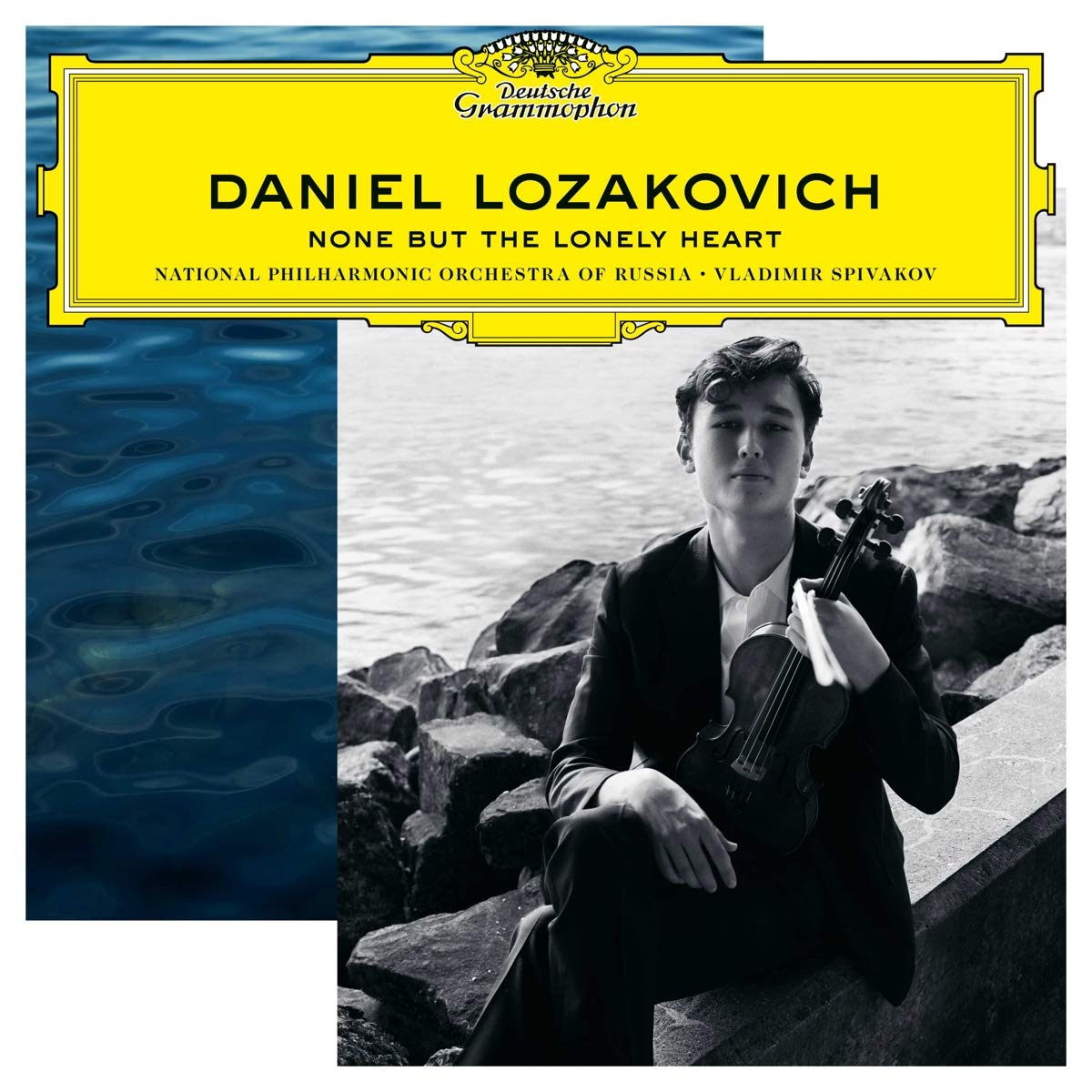

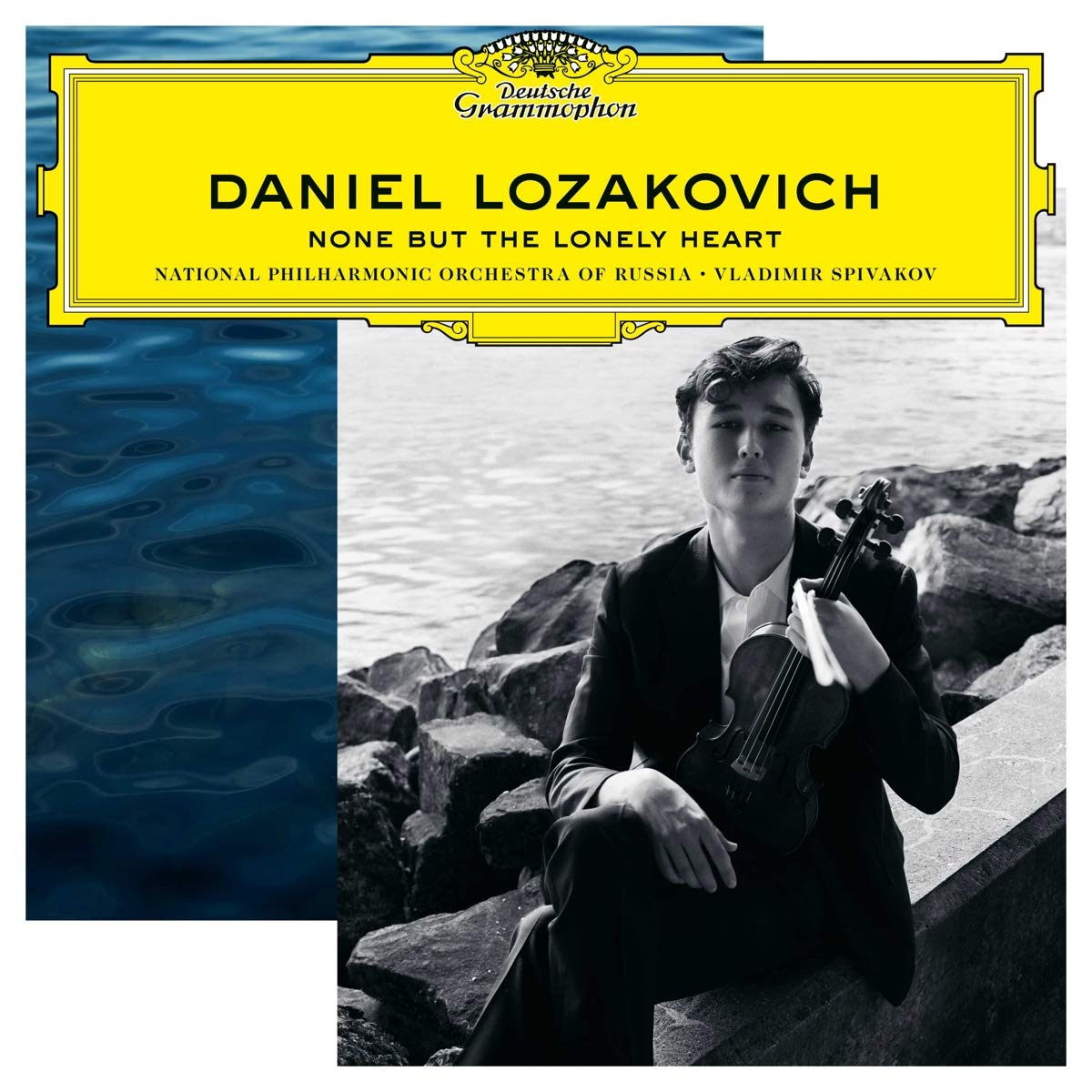

“None but the Lonely Heart”

Tchaikovsky – Violin Concerto, Arrangements

Daniel Lozakovich – Violin

Russian National Philharmonic

Vladimir Spivakov – Conductor

Deutsche Grammophon, CD 0289 483 6086 4