By the late 1790s Beethoven was spending much of his summers in the country. Charles Neate, a friend who spent the summer of 1815 taking long walks with him, later recalled he had never met anyone “so delighted by Nature or who so thoroughly enjoyed flowers or clouds or other natural objects.” Beethoven himself wrote “No one can love the country as much as I do.” Writing a “nature” symphony, therefore, must have had special meaning for the composer.

Beethoven’s first sketches for the work date from 1802, but the symphony was only completed in August 1808. It was first heard at the (in)famous December 22, 1808 concert held in a frigid Theater an der Wien, the four-hour program including premieres of the fifth and sixth symphonies, fourth piano concerto, and Choral Fantasy.

There is still some debate as to whether the sixth is “program music,” which the Oxford Dictionary defines as “music that is intended to evoke images or convey the impression of events.” While there are certainly passages that match this description (the end of the second movement, the fourth movement “storm”), Beethoven is more intent on ensuring the listener experiences the peace and tranquility he found in nature. He believed the listener should “discover the situations himself, as all tone painting in instrumental music loses its value if pushed too far,” even suggesting “The whole will be understood even without a description, as it is more feeling than tone-painting.”

Beethoven – Symphony No. 6 – Analysis

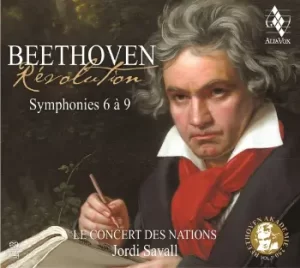

For a full description of Sonata form, refer to the guide on Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5. All timings refer to the recording by Le Concert des Nations and Jordi Savall (see below).

Movement I: “Awakening of Happy Feelings on Arriving in the Country.”

The opening measure steals in, but just as quickly comes to a stop. An unassuming beginning, but Beethoven now uses this initial melodic and rhythmic material to fashion motifs that are repeated and developed throughout the movement. For example, listen to the passage beginning at 0’20”, where the notes are identical (though there is constant dynamic variation) and to the same five-note motif repeated for 36 measures at 4’54” and then for another 36 measures at 5’38”.

The almost exclusive use of major keys in root position (the Development moves through B-flat to D to G to E major) defies expectations, as do the many moments of harmonic stasis. One such moment is the example of melodic repetition mentioned above: starting at 4’54” the first 12 measures are in B-flat major, answered by 24 measures in D major. Audiences of Beethoven’s time would have expected a Development section built on harmonic clashes and conflict that then worked towards resolution and stability (the arrival of the Recapitulation – indeed, that is a perfect description of the harmonic process in the fifth symphony’s first movement). Yet here Beethoven subverts that expectation to create the feeling of standing still to take in the beauty and majesty of the natural world.

Why did Beethoven use so much repetition? Beethoven scholar Anthony Hopkins argues: “One of the most notable characteristics of the entire first movement is its exploitation of repetition, the repetition of pattern that we find throughout nature…Beethoven is concerned to capture both the infinite similarity and the infinity variety of nature’s patterns.”

Movement II: “Scene by a Brook.”

In his early sketches Beethoven made two notes: “murmur of the stream” and “the more water the deeper the tone.” The hushed opening depicts the brook’s gentle flow, two cellists mimicking the water’s undulation on muted strings as the remaining cellos play mostly pizzicato notes with the double basses. Interestingly, the melody’s opening gesture seems reticent to leave the B-flat tonic (home note), only increasing in range at measure five. The clarinet and bassoon then take over, first stating the melody in unison (0’32”) and then in canon. A more delicate version of the melody returns to the first violins, as lower strings continue to simulate the ceaseless current underneath.

At 2’14” the violins introduce a more expansive and passionate second subject, leading to the forte (loud) marking at measure 37. A third subject, still more ardent, appears in the viola and cello at 3’54” and is treated contrapuntally, Beethoven layering and interweaving the various melodies until the music reaches the coda. While this movement is famous for its concluding bird calls, the impersonation actually begins much earlier (0’34”) with high trills in the violins. The distance between the low and high strings is a spatial realization of birds flitting about in the branches above the brook. Note too, how the texture is fuller (“deeper in tone”) around 7’10”, as if the brook has now become a river.

The well-known bird calls in the Coda have symbolic significance: the nightingale (flute), love and sweetness; the cuckoo (clarinet), harbinger of summer. The Quail (oboe) has religious overtones: Beethoven had composed a song in 1803 in which the quail worships God. Beethoven believed all of nature worshipped the Creator, once writing “It seems as if in the country, every tree said to me, “Holy, Holy.”

Movement III: “Joyful Gathering of Country Folk”

The next three movements play without pause. Beethoven alters the usual ABA form to: Scherzo (in 6/8) – Trio (in 2/4) – Scherzo – Trio – abbreviated Scherzo. This is the first appearance of people, and they disrupt the genteel atmosphere of the first two movements with a bawdy peasant dance. In the first minutes Beethoven juxtaposes two phrases of contrasting tonality and articulation: the first, played by the staccato strings in F major, answered by a legato second phrase in D major played by strings and woodwinds. He also adds little touches of humor, perhaps poking fun at the village band (0’52”): the oboe’s syncopated melody never quite lands on the downbeat, while the bassoon player apparently only knows how to play two notes. The Trio (1’33”) is especially vigorous with sforzando accents that stomp on the first beat of each measure, and the final scherzo is quickly upended (4’30”) when the orchestra suddenly plays fortissimo (very loud) and presto (very fast), dancers and musicians scattering before the approaching storm.

Fourth Movement: “Thunder. Storm.”

The calm and playful atmosphere of the previous movements is dispelled in music of brutal force. The constantly shifting chromatic harmony, numerous diminished-seventh chords, and asymmetric phrases negate all sense of stability. Beethoven also returns to an idea first explored in the fifth symphony, adding instruments that have remained silent in the opening three movements to create unique orchestral colors that heighten the pictorial and emotional impact. Timpani are heard for the first time at 0’28”, soon joined by the fearful cries from the piccolo (2/03”), climaxing with a final lightning strike that includes two trombones (2’04”). The storm then recedes, dynamics steadily softening, as the oboe introduces a tender melody that is answered by a delicate, ascending scale in the flute – perhaps the moment a rainbow appears?

Movement V: “Shepherds’ Song: Happy and Thankful Feelings After the Storm.”

The opening eight measures, quoting an Alpine horn call, serve as introduction to the first theme which begins at 0’17”. The theme is the shepherd’s song of thanksgiving, simple and folk-like, built from arpeggiated triads, played in symmetrical eight-bar phrases. First played by violins, clarinet, and low strings, its orchestration is fuller with each restatement. The second theme (1’05”) is livelier still, its trills and staccato articulation recalling the bird calls of the second movement. Harmonies are again predominantly major and in root position, restoring stability. The long coda (beginning at 5’42”) repeats a major-chord progression (D to G to C to F) seven times (in variation of course!) connecting the first and last movements. In the final minute Beethoven recalls motifs from the brook scene, the horn makes one final Alpine call, and the work ends with two affirming F major chords.

Beethoven – Symphony No. 6 – The Best Recordings

As with all of Beethoven’s symphonies, the listener has dozens of choices when it comes to recordings of the sixth. Every major orchestra and conductors recorded the symphony, most few time over. The following features performances from various decades, a mixture of modern and original instrument performances.

Herbert von Karajan, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (1963 cycle)

Karajan recorded complete cycles of the symphonies several times (including two for video), but his first cycle with the Berliners is generally considered his finest. The 1960s sound, especially in this new remastering, is better than what was achieved in the late cycles, and the mannerisms that crept into Karajan’s interpretations are not yet evident in this series. His reading of the sixth is wholly unaffected and deeply felt, with fabulous orchestral playing.

Sir Charles Mackerras, Scottish Chamber Orchestra

Mackerras recorded a successful cycle with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic in the 1980s, and again with the Prague Chamber Orchestra in the 1990s, but his live set with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra was finer still. Mackerras had spent a lifetime studying and adopting historically informed performance practice into his performances, and the results as recorded here are utterly natural and entirely convincing. This performance of the sixth is impassioned, vibrant, and deeply touching.

Sir John Eliot Gardiner, Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique

The period instrument craze exploded in the 19080s, with cycles of these works by Goodman, Norrington, Hogwood, and Bruggen. Gardiner and his forces entered the field a bit later, with orchestral playing of greater finesse and physical power than previous cycles, caught in startling immediate Archiv/DG sound. The sixth receives a raw, elemental reading, honoring the composer’s quick metronome markings, and a particularly fierce storm. The symphonies are available in their own box, but this recording gathers all of Gardiner’s Beethoven performances in one box that is well worth the modest outlay.

Jordi Savall, Le Concert des Nations

This recent cycle, recorded before, during and after the pandemic, features performances of fire and finesse. Savall’s reading is atmospheric and stunningly played, with especially seductive and characterful playing from winds. The recording ensures we hear every strand of the score with crystalline clarity while the sense of gratitude and praise in the final movement is overwhelming in its impact.

Karl Bohm, Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

This 1971 recording by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra was considered a go-to version for many years, and rightly so. It incorporates the Vienna Phil’s golden sound like few recordings do, and exemplifies a Beethoven playing which was very common – one of serious, measured, and respectful of playing tradition no less than the written score.

Support Us

We hope this guide has helped you navigate the wonderful world of classical music! If you enjoyed this free resource, consider making a donation to The Classic Review. Your generosity helps us keep the music playing by allowing us to publish informative guides, and insightful reviews. Every contribution, big or small, allows us to continue sharing our passion for classical music with readers like you.

Donate Here