Last updated: December 23, 2024.

On 20 November 1889, Gustav Mahler conducted the premiere of his five-movement “Symphonic Poem in Two Sections.” Regrettably, much of the audience found it incomprehensible: while the first section (movements 1 and 2) was warmly applauded, the second section produced a noticeable change in the audience’s mood. By the end, there was small but audible opposition and Mahler, bitterly disappointed, set the work aside.

Preparing for its second performance in 1893, Mahler made significant revisions. The music was now a “tone poem in symphonic form” called “Titan.” Mahler wrote a program suggesting the music described Jean Paul Richter’s “Titan,” in which the main character strives to lead a passionate, noble and heroic life – ideals with which Mahler greatly identified.

By 1896, the title, program note and “Blumine” movement were dropped – the work was now “Symphony No. 1 in D Major.” Yet, even with all these changes, and the fact that Mahler conducted quite a few performances of it, the symphony never received the acclaim Mahler felt it deserved. Over a century later, Mahler would be pleased that the Symphony is recognized as one of the most impressive and audacious first symphonies ever written, with over 150 available recordings.

Mahler, one of the leading conductors of his day, was intent on continuing the symphonic tradition of Beethoven, Brahms, Schumann and Bruckner. But he was also fully immersed in the late-romantic and modernist ideas of Liszt and Wagner. His meshing of traditional and modernist ideas in his symphonies makes his oeuvre particularly innovative.

The first symphony’s orchestration was particularly large for a symphony of that time. (Mahler exceeded this size in his very next symphony.) Yet, the primary reason for enlarged forces is not overwhelming volume, but rather an expanded palette, which enables Mahler to create individualistic instrumental timbres.

More Classical Music Guides

- Beethoven – Symphony No. 5 – A Beginners Guide

- Guide: Classical Music For Children

- Mozart – Requiem – A Beginners Guide

Mahler utilized different types of music, such as folk-dance, songs and band music, as thematic fodder in his symphonies. This was offensive to many who believed this such music unsuitable to the artistic integrity of the exalted symphony. And these symphonies are often quite long: the first and fourth, at under an hour, are the two shortest. The third lasts almost two hours. All of them require patience and repeated listening to reveal their many wonders.

Mahler – Symphony No. 1 – Analysis

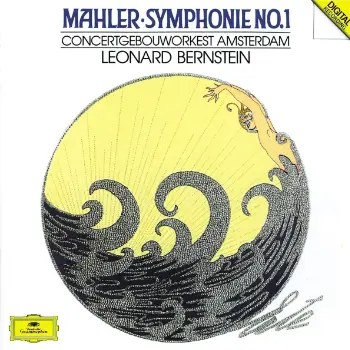

The timings that appear in this guide is based on Leonard Bernstein’s recording of this Symphony with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra on Deutsche Grammophon, mentioned as one of the top recommendations below.

Movement I: Langsam. Schleppend (Slowly. Dragging.)

The opening A pitch, played by the string across seven octaves, is potently evocative. This unique effect is created by strings divided into nine sections, eight of which play the pitch as a harmonic. Woodwinds imitate bird calls (a descending fourth), and moments later the clarinets gently imitate a trumpet fanfare. This is soon answered by actual trumpets, playing off-stage to sound “at a far distance.” Horns then present a melody evoking a languid summer morning, which the trumpets rudely intrude on with continued fanfares.

This numinous mood leads into the first main theme (3’39”), its melody taken from Mahler’s song, “Ging heut morgen über’s Feld” (This morning I walked across the field). Confident and optimistic, the theme begins with a descending fourth which connects it to the opening moments. The music becomes increasingly active, the melody traded between instruments and embellished by other various “nature sounds.” This “exposition” is then repeated, following expected sonata form.

At 7’50” the development” begins, recalling the opening music as the cellos struggling to develop a full melody from the descending fourth motive. The harmonic shift at 9’10”, marked by a gentle thwack on the bass drum and a subdued low F in the tuba, sets a more foreboding atmosphere. Darker harmonies, girded by a barely audible bass-drum roll, build tension until another harmonic side-step into the home key discharges the accumulated tension. The short trumpet fanfare from the beginning is now played and extended by the horns (11’07”). The music has moved into the “recapitulation,” but Mahler dislikes exact repetition, so he develops the song theme even more. The mood again darkens at 13’12”, the brass fanfares turning ominous as lower strings propel the music towards its first real climax (14’38”). This brings another discharge of tension, horns whooping their collective joy. The movement ends in celebration of youthful vitality, getting progressively faster, or as Mahler describes: “my hero breaks out in laughter and runs away.”

Movement 2: Kräftig bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell. (Moving vigorously, but not too fast.)

Mahler uses the expected A-B-A structure, but not the expected “dance.” Haydn would have written a Minuet, and Beethoven later changed it to a Scherzo. Mahler uses a “Ländler”. The opening music stomps out a repeated descending fourth figure, with a melody that essentially arpeggiates an A major chord. At 1’50” Mahler has clarinets and oboes lift their bells above the music stands, ensuring the melody stands out – this is a technique he used in every one of his symphonies. A funny detail appears at 3’55” as trombones, tripping behind the rest of the orchestra, create a delightful syncopation.

The B section, slower and more lyrical, shifts the harmonic center from A to F major. Elegant sophistication replaces peasant folksiness, in music that is sweetly tender and gently playful. The return of the A section is abbreviated, leading to a vigorous, joy-de-vivre conclusion.

Movement 3: Feierlich und gemessen, ohne zu schleppen. (Solemn and measured, without dragging.)

The previous movement’s joy is immediately dispelled: again we hear the interval of a fourth in a bass ostinato (defined as a repeated melodic or rhythmic figure), over which a muted solo contrabass plays “Frère Jacques” in minor. Mahler described it as “A funeral procession passes by our hero.

The bass solo develops into a canon, played by various soloists as woodwinds introduce a laconic countermelody (1’05”) that ignores the overall mood. At 2’09” the oboes play klezmer-like music, eventually overtaking the funeral procession, percussion providing an oom-pah accompaniment (2’41”) as the strings play their part “col legno” – with the wood of the bow.

A new melody gradually returns the music to its original mood. At 5’05” there is a marvellous change in key and tone as Mahler adopts another song, “Die zwei blauen Augen” (The two blue-eyes of my beloved). The words of its final stanza reveal Mahler’s intent: sitting under a linden tree the protagonist, contemplating the loss of his first love, feels he can “rest in sleep.” The loss of his first love is overwhelming – he now wants to bid farewell to a life where his “companions were love and suffering.”

The opening music returns at 7’14, but is quickly interrupted by the Klezmer music, more obnoxious and discursive than before. The music climaxes at 8’30,” as Mahler layers the three movement’s three melodies on top of one another – is this to remind us that in life, joy and sorrow always coexist? The original mood returns, the insistent tread of fourths ending with two dull thuds.

Movement 4: Stürmisch bewegt. (With stormy emotion.)

Mahler described the opening measures as “the outcry of a wounded heart.” Even without a program, we clearly hear this as music struggling to overcome darkness. Indeed, the opening thunderclap knocks our hero down to the ground. At the most basic level, the struggle is represented by 2 four-note motifs, one ascending (0’09”, the other descending (0’12”). These two motifs, battle through a dense contrapuntal texture until they exhaust one another.

At 3’32” another gorgeous harmonic shift establishes an entirely different mood, songful and filled with tender regret. Gradually the music grows in melodic range and dynamics, releasing in a powerful climax at 5’51.” Rejuvenated (heard in a slowly ascending chromatic cello line and the return of those 2 four-note motifs), the hero readies himself for another fight.

The battle begins at 7’21,” brass blasting out the ascending figure as woodwinds and high strings surround it with hectoring, chromatic, lines. Brass intone a chorale-like figure (8’07”) suggesting impending victory, but woodwinds and horns respond with the descending four-note motif. The chorale theme returns (9’33”), setting up a powerful climax into C major, but the entire orchestra overshoots, landing in D major. Mahler described the moment: “my D chord had to sound as if it had fallen from heaven, as if it had come from another world.”

The forced arrival does not end in victory, instead retreating into a remembrance of the opening of the first movement. Motifs from the first and last movements are combined until the oboe, then violins, lead us into imploring, angst-ridden melody at 14’23.” This builds into an overwhelmingly emotional climax – perhaps the catharsis our hero needs – as he once again returns to battle. This time the chorale theme signals complete victory, the horns presenting a countermelody seemingly related to Handel’s “And he shall reign” from his “Hallelujah” chorus. With the orchestra ostensibly at peak decibel level, Mahler tells the horns to stand (18’43”) and blast the “And he shall reign” theme over the rest of the orchestra – a moment of exultant jubilation.

Mahler – Symphony No. 1 – The Best Recordings

Concertgebouw Orchestra, Bernstein

The Concertgebouw Orchestra is in stunning form, fully realizing Bernstein’s vision of the piece. Bernstein’s reading of this symphony was always impetuous and ardent: in a reading filled with wonderful moments, the Coda is absolutely life-affirming!

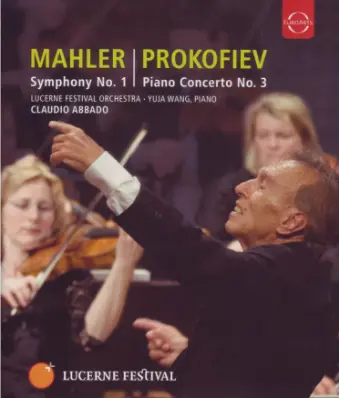

Lucerne Festival Orchestra, Abbado

Abbado’s earlier Mahler performances were, for some, overly fussy and superficial, but in this video performance of the first symphony everything seems to fall into place in a reading that is ravishingly beautiful and deeply meaningful in equal measure.

Find offer for this album on Amazon (video files)

Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, Nézet-Séguin

There is a justly famous recording of this symphony, featuring this same orchestra under Rafael Kubelik on DG. BR Klassik’s more recent recording, led by Nézet-Séguin, is arguably even better, a fresh and youthful reading that features wonderful playing and scrupulous attention to the score – I think it is Nézet-Séguin’s finest Mahler recording.

London Symphony Orchestra, Solti

Solti’s first recording of this symphony is brimming with energy and splendid playing by the London Symphony Orchestra. The mid-1960s recording remains impressive and is far better than many more modern releases.

Hungarian National Philharmonic, Kocsis

Finally, a difficult to find recording that is well worth finding. The Hungarians may not be a match for other orchestras on this list, but their passion and commitment leaps out of the speakers, making this an especially involving performance. It also includes the most pervasive performance I know of the discarded “Blumine” movement.

Included with an Apple Music subscription:

Available on Presto Music

Latest Classical Music Posts

Read more classical music reviews or visit The Classic Review Amazon store