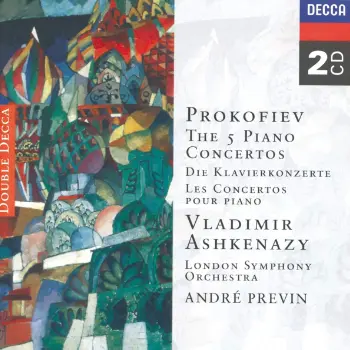

Editor’s note: Timings on this guide are taken from Vladimir Ashkenazy’s recording with the London Symphony Orchestra under André Previn (Decca):

Prokofiev’s third piano concerto stands out from the rest of the composer’s 5 piano concertos for its unusually long gestational period. Sources indicate that Prokofiev started on it as early as 1911-1913; however, the work itself came to fruition over a four-year period from 1917-1921. The opus was a product of his lengthy self-imposed exile from Russia, which also saw the birth of two operas including the Love for Three Oranges, Violin Concerto No. 2 and a good handful of his symphonies and ballets.

On December 16, 1921, Prokofiev himself gave the premiere with the Chicago Symphony, but not without acknowledging the trepidation he had about his own output. In a letter to Serge Koussevitzky shortly before the performance, he remarked: “My Third Concerto has turned out to be devilishly difficult. I’m nervous, and I’m practicing hard, three hours a day.”

Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3 stands out as his finest concerto writing (alongside his Piano Concerto No. 2), and remains audience favorite and a staple of the piano competitions repertoire.

Prokofiev – Piano Concerto No. 3 – Analysis

While the concerto is a quintessential reflection of Prokofiev’s vibrant twentieth century stylistic language, it is also a fine example of neoclassicism, including the choice of composing 3 movements in a fast-slow-fast tempo format. The neoclassicism also manifests itself in the structure of each movement (as explained below), yet the concerto as a whole offers a dynamic combination of romantic, modern, and even baroque elements.

Movement I: Andante – Allegro

While Prokofiev divides this movement into three main parts like a traditional A-B-A structure, he doesn’t adhere to conventional development methods; the piece is primarily driven by thematic transformation.

The movement begins with a solo clarinet introducing the first theme. This melodic opening, followed by a full orchestral introduction, might lead one to expect a grand, symphonic piece. However, Prokofiev’s signature humor soon becomes apparent.

It turns out that the expansiveness is just a front for the electric energy that emerges in the ensuing passages (0’48): the helter-skelter dialogue between piano and orchestra is punctuated with more than a few violent, dissonant crashes before a commanding arrival at A minor. This B section is marked with the introduction of a sardonic second theme (2’26”), where Prokofiev chooses to pair the oboe melody with castanets, producing spirited clicks that give this section its unforgettable bite.

The midway point is marked by a return of the sweeping theme (4’14”), followed by a moment’s respite. The quieter moments are where we hear a more introspective version of the original theme in the piano, but also some beautiful dovetailing with select woodwinds. The eventual return of the A section (6’23”) includes a difficult octave doubling, thickening of the piano’s running passages (6’54”). The final moments are marked with the reappearance of the castanets. The indomitable frenetic spirit hits its peak in the quick harmonic changes and crystalline dissonances, closing the movement with an added bass-drum.

Movement II: Tema con Variazioni

This middle movement, structured as a theme with 5 variations and a coda, reconciles two very different features: a Baroque gavotte colored with Prokofiev’s own ballet-like touches.

The orchestra introduces the theme in a tonal fashion, yet the piano transforms it into something more colorful in the first variation (0’59”). In the subsequent installments, we hear even more multifaceted aspects of transformation: Variation 2 (2’05”) puts an urgent and ferocious spin on the theme. Listen also for the polytonality introduced when the brass takes over the theme. The third variation (2’51”) essentially deconstructs the theme via hefty syncopations, lending it its distinct, primal character.

As for the fourth (4’01”), although it is the slowest variation, it might be one of the most interesting musically. A recurring motif of descending thirds in the piano appears in intimate eeriness and chilly dissonances, adding an element of the macabre. Prokofiev indeed includes a unique marking of freddo (cold) in the score, perhaps encouraging the performers to evoke the dark solitude as time seems to stand still (the entire variation is marked “Andante Meditativo”). The pace picks up in the rousing fifth variation (6’37”) before the coda, and a restatement of the theme.

Join The Classical Newsletter

Get weekly updates from The Classic Review delivered straight to your inbox.

Movement III: Allegro ma non troppo

As with the earlier movements, it is a woodwind (the bassoon in this case) that kicks things off with a sprightly theme. Its unadorned nature affords Prokofiev to utilize thematic development and transformation. The entrance of the piano replaces the light, singular-note textures with something much more substantial, reminiscent of the austere Dance of the Knights from his Romeo and Juliet suite. The central martial character that soon materializes has two sides: an adventurous, swashbuckling presence via the piano’s glissandi, and a more broody aspect that emerges in the low strings and winds.

This movement may possess the most thematic variety of all three, as a rather eccentric and enigmatic melody materializes midway, lingering in a quirky dialogue between both parts. But the most memorable is the soaring, lyrical melody that Prokofiev juxtaposes shortly thereafter (2’44”): its cinematic and rhapsodic profile sets it apart from anything we’ve heard earlier.

Much like the first moment, the ending brings back the main melody but in a shorter, faster version (7’37”). A skillful layering of sounds naturally builds tension, catapulting the music into a cataclysmic yet brilliant conclusion.

Prokofiev – Concerto No. 3 – The Best Recordings

Given the popularity of this concerto, there is a plethora of recordings available. Below are some canonical and more recent versions that prove equally valid for getting acquainted with the Concerto.

Martha Argerich, Claudio Abbado & Berlin Philharmonic

This is one of those recordings that should find its place in any listener’s collection, Prokofiev and beyond. While some may lament that Argerich tends to take an extremely brisk take on pacing, it works well to highlight the furious, frenzied energy crucial to the music. As a technical showpiece, Argerich lets fingers fly effortlessly in the most challenging passages, but kudos are also in order for Abbado and Berlin players. They manage to keep up nearly perfectly with their soloist’s synchronicity and drive.

Vladimir Ashkenazy, André Previn & London Symphony Orchestra

This is a canonical version that dominated the catalog since its appearance in the mid-1970s. While Argerich breezes past some passages in impressive fashion, Ashkenazy takes a more heady approach: listen, for instance, to the opening of the first movement. Accents are more deliberate and the dotted rhythms more insistent. The third movement is where the verve is most present; it almost feels like Ashkenazy pushes the instrument itself to its limits in the empathic phrasing and crashing chords. However, the sound never exceeds a level unpleasant to the ear.

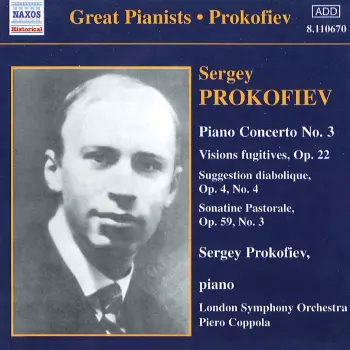

Sergei Prokofiev, Piero Coppola & London Symphony Orchestra

This 1932 recording made by the composer is admittedly not of the best quality, but if we listen through the fuzz, there’s plenty of enjoyable insight. The performance shows that, despite Prokofiev’s misgivings about the difficulty of his own work, he meets his own challenge. The orchestra, on the other hand, seems to have a harder time keeping pace with the soloist, although the playing itself is quite solid. Oddly enough, these moments of mismatch add to the raw furor of the music. Prokofiev’s own interpretation of the second movement (Var. 1 in particular) may come as a bit of a surprise for those expecting a more lyrical account; while fluid, his playing has an impetuous push to it.

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, Giancarlo Noseda & BBC Philharmonic

While the rather slow opening and thinner sound of the first movement’s opening might raise some eyebrows, things are quickly set right. The BBC Philharmonia’s passagework is intricate and suspenseful, but also sharp and intense when needed.

Bavouzet takes the light touch that he used so well in his Ravel recordings: his upper register sonorities complement especially well the sounds of the flutes when such pairings appear. There are times when the lightness hovers barely above a whisper, but this only heightens the abrupt contrasts in the music. The volatility that Bavouzet maintains throughout proves central to the excitement of this interpretation, one of the more successful from the digital era.

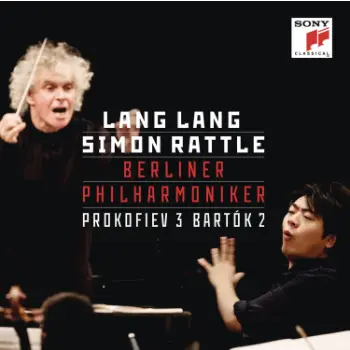

Lang Lang, Sir Simon Rattle & Berlin Philharmonic

Lang Lang’s signature technical facility is on full display in the outer movements, and this energetic performance helps play into the composer’s signature dry humor. Yet for all the virtuosity, listeners will be pleasantly surprised by the pianist’s buttery, mellow tone and subtle responsiveness to harmonic colors. This album generously includes another highly demanding work – Bartók’s Piano Concerto No. 2. Fantastic recording quality too, especially in Dolby Atmos.

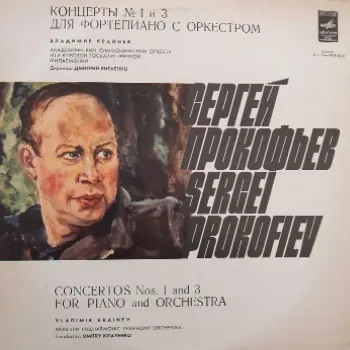

Vladimir Krainev, Dmitry Kitaenko & Moscow Philharmonic (Melodiya)

Vladimir Krainev and Kitanko recorded the Prokofiev concerto cycle twice (the second time in the ‘90s with the Frankfurt Orchestra), but this earlier cycle of the 5 concertos, recorded between 1976 and 1983, stands out. True, the sound engineering and acoustics are sometimes scrappy at best, but they definitely add to the unique charm of this thrilling interpretation.

Krainev’s approach is founded in deliberate keyboard strikes that can sound punch but undeniably enthusiastic. This proves refreshing in the outer movements and especially the Finale, where the pianist’s unabashed accents and chords unleash an almost terrifying intensity. Even in the quieter moments, there is a sinister and unstable presence always lurking. The orchestral playing may not be the most integrated, but the pointed appearance of certain instrumental lines brings to light individual characters we might miss in other recordings.

Top Image coloring: ©️ The Classic Review