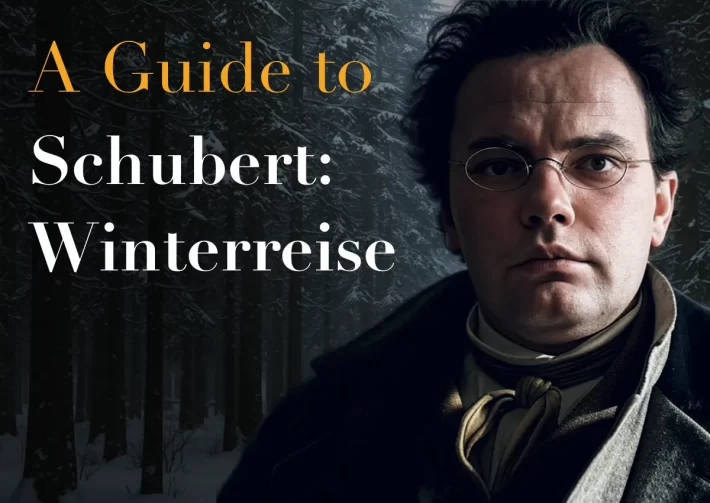

With two defining song cycles, Die Schöne Müllerin (1823) and Winterreise (1827), Franz Schubert established himself as a master of the 19th-century lied. Written for tenor and piano and set to poems by Wilhelm Müller (1794-1827), both canvas a broad emotional spectrum as it relates to love. But where the earlier cycle has a more story-like arc, Winterreise delves deeper into the psyche.

Schubert – Winterreise – A History

Schubert once called Winterreise a cycle of “truly terrible songs,” not only for its immersive and dark subject matter but also for the compositional process itself. His manuscript (available digitally to those curious via the Pierpont Morgan Library) reveals quite a bit: in Einsamkeit (12), sheer frustration is forcefully etched onto the page while in Errstarung (4), his penmanship shows the notes hitting the page as swiftly as the actual tempo of the song.

Schubert based his composition on the writings of his contemporary, Wilhelm Müller, considered by some sources at the time to be little better than a second-rate poet. Schubert first came across Müller’s material in the early 1820s, namely Vol. 1 of his poems from The Posthumous Papers of a Traveling Hornplayer, which eventually served as the basis for Die Shöne Müllerin.

Schubert had originally intended Winterreise to be just a dozen songs, set to Müller’s 12 poems that appeared in an 1823 literary publication, Urania. He completed the settings early in 1827 only to then discover that Müller had a second volume of the Traveling Hornplayer. These proved compelling enough for him to double the length of the cycle and to arrange the songs into their current order.

Schubert – Winterreise – Analysis

Two recurring themes in the cycle are contrast and the unexpected: on more than one occasion, there appears to be divergence, sometimes so subtle, between the character of the words and the music. Perhaps this was Schubert’s way of portraying irony and fate or even conflict: hope vs. despair and the want for connection vs. the reality of loneliness. The songs below highlight several important moments during the course of the journey.

Whereas the opening of Die Schöne Müllerin (Das Wandern) has a resolute optimism, Winterreise’s Gute Nacht (1) is wistful and somber, making clear the precedent: though once betrothed to his beloved, the traveler’s circumstances have changed. Now alone, he recognizes the need for a quest, a journey that might somehow yield personal revelations. Schubert’s writing amplifies the poem’s meaning and then some–the descending right hand piano figures which begin each stanza seem to symbolize the fatality that will pervade the rest of the cycle. What makes this all the more poignant is how the vocal line is still filled with a gentleness when the narrator bids his former lover goodnight.

Der Lindenbaum (5) exemplifies the irony of contrast. Sonically, it is one of the rarer songs that exudes a wholly contemplative warmth and calm. Müller’s text, however, says otherwise: the linden tree represents joy and sorrow, rest and nostalgia. Conflict becomes most overtly evident in the music of Frülingstraum (11), where there is a stark and sudden danger that overtakes the beguilingly pastoral opening. This song also bears the first mention of crows, which become a sinister symbol moving forward as we hear in the haunting Die Krähe (15).

Die Poste (13) marks both the halfway point and, fittingly, the highest emotional moment for the protagonist. Hearing a posthorn, he yearns for news from his beloved. For all the song’s optimism, one cannot help but conceive of a stinging irony in his excitement. While Schubert’s piano textures most obviously mimic the galloping of the postman’s horse, the rhythmic certainty could also be a nod to the narrator’s elation and his own heart that he references at the end of each stanza.

Müt! (22) marks a final psychological stand for the narrator. The chords burst with a steadfastness and energy that is in stark difference to the lyricism of the surrounding songs. Text-wise, the final line (‘if we can’t have gods on earth, we are gods ourselves’) might garner a bit of interest. One cannot help but wonder if the narrator is so emotionally taxed at this point that he’s become almost delirious or whether this could be a heroic realization of his solitude.

Like Die Wirtshaus (21), the calmness of Die Nebensonnen (23) belies the poem’s riveting message. Its description of the disappearance of three suns in the sky is a metaphor for the sobering realization that loneliness is inevitable. In the vein of the unexpected, the divergent dichotomy between music and text does not lead to conflict in this case, but rather profundity: the calm in fact speaks to an admission of finality and of where his journey has ultimately led.

Where there is a definite sense of closure in Die Schöne Müllerin through the death of the protagonist, Winterreise leaves us with the esoteric Die Leiermann (24). Here, the desolate traveler notices a lone hurdy-gurdy player in the distance, ignored and unable to procure any alms. The final line of the poem (“Shall I go with you? Will you play your hurdy-gurdy as I sing my songs?”) forever remains a rhetorical question but sheds a fleeting and again ironic light upon the connection the two men have to each other: solitude. The compositional textures prove to be just as enigmatic as the words themselves. The piano’s drone ostinato creates a static, hollow soundscape that the vocal line must fill. Unlike the earlier songs, however, it offers no real sort of complement or comfort in the way of floridity or movement. And so, the listener too must finally come to terms with–and experience firsthand–the narrator’s feelings.

Schubert – Winterreise – The Best Recordings

For even the finest singers (and pianists for that matter), Winterreise has proven to be the work of a lifetime. This is evidenced by the multiple versions and collaborations many have left behind. A number of superb recordings, alas, have found themself out of circulation as a physical CD but can be enjoyed on streaming services. These include Dietrich Fischer-Diskau’s collaboration with Gerald Moore (EMI, 1962) or Thomas Quasthoff’s live performance with Daniel Baremboim (DG, 2005).

Below you can find recommended (and available) albums for listeners who first come to Winterreise but which will also offer the seasoned listener a lifetime of enjoyment.

Hans Hotter (bass-baritone) & Gerald Moore (EMI, 1954)

Hotter recorded the cycle four times but the 1954 stands out, owing to the combination of his insightful bridging of text and music and Moore’s fine pianism–a testament to the rare finesse that modern recordings can’t quite replicate. Der Krähe (15) is striking in how evenly Hotter treats the lines, almost as if to show that sadness has evolved into emotional numbness. This sets up a riveting contrast, however, to the peaks of certain phrases that come at us full force. Moore’s measured triplet figures evoke the dogged footsteps of the traveler. The duo’s funereal Der Leiermann (24) could very well let us believe the narrator has died psychologically. Yet, listen closely and one will perceive how Hotter’s careful shaping of phrase endings reflects a gentle pity for his plight

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (baritone) & Jörg Demus (DG, 1966)

Fischer-Dieskau made seven commercial recordings, the most being with Gerald Moore (1955, 1962, 1973) but also with Jörg Demus, Alfred Brendel, Daniel Barenboim, and Murray Perahia. The Demus version (1966) remains as one of the landmarks and for good reason; where the 1955 shows a younger and expressively eager singer, the 1966 shows just how beautifully time has tempered the interpretative approach. In Gute Nacht, for instance, Demus takes a slower tempo than Moore, but Demus’ left hand bears an almost perfectly metronomic consistency that can be likened to the throb of heartbeat or the plodding of footsteps. Consequently, the urgency of the baritone’s 1955 account that rushes the phrases forward has turned into something more mellifluous and reflective. Die Nebensonnen is another fine example of refinement: the singer adds a hint of defiance to the expansive major sections, almost as though he’s not ready to let the protagonist resign himself to fate. In the minor sections, we can savor the lovely sostenuto within the wistfulness.

Peter Schreier (tenor) & Sviatoslav Richter (Decca, 1985)

Schrier took an interesting route with Winterreise over the course of his career: this live recording with Richter, one with Andràs Schiff (1994), and a version arranged for voice and string quartet in 2005. The 1985 for me stands out with its musicianship, which we hear in songs like Errstarung (4). Schreier infuses the phrases with an insistence that really gets us at our core. Richter’s accompaniment supports the singer with a reasonable tempo but has a character of its own, as heard in the transition from the lyrical to more determined moments. A parallel listen here to the Schiff collaboration is worth it: Schiff’s drier, more aggressive figurations certainly fuel the excitement, but the brisk pace proves a bit too unsettling at times. The audience’s coughs at the beginning of Das Wirtshaus (21) are frustrating given Richter’s extremely nuanced and emotionally convincing introduction. Schreier is at his best as he sheds light on a rare angle: the protagonist’s weariness within the solace.

Brigitte Fassbaender (mezzo-soprano) & Aribert Reimann (EMI, 1988)

There have been a handful of mezzo-sopranos who have approached the cycle including Lotte Lehmann (the first woman to perform and record it), Brigitte Fassbaender, Christa Ludwig, Alice Coote, and most recently, Joyce DiDonato. Fassbaender’s leaves a strong impression partly for some interesting but finely executed interpretations like Gute Nacht. Contrary to others, Reimann’s piano introduction is weighty, even dramatic and the mezzo’s rich timbre and phrasing are an equally substantive match. The small slides she adds between certain notes, for instance, adds that extra bit of dolefulness. Einsamkeit (12) has an operatic quality that one cannot forget and moments of huskiness speak to the protagonist’s visceral pain.

Jonas Kaufmann (tenor) & Helmut Deutsch (Sony Classical, 2014)

For those in search of a more extroverted Winterreise, the Kaufmann/Deutsch collaboration will certainly do. Combined with the tenor’s rich and substantive tone is a passion we hear in selections like Errstarung (4): the convincing phrasing recreates the main character’s reaching and yearning. Meanwhile, Deutsch provides the element of balance by taking a sensible tempo but one that also allows the intricacy of the triplet patterns to come through clearly. On the opposite end of the spectrum character-wise is Auf dem Flusse (7), with a lot of subtlety in the singer’s color changes and the pianist’s attention to articulation. In Tauschung (19), Deutsch adds an intriguing lilt to the waltz pattern to create a skipping feel. Great voice control from Kaufmann reveals a personal undertone under the lighter melody–it really does seem that the main character is singing only to himself, which indirectly heightens the cycle’s overarching theme of solitude.

Ian Bostridge (tenor) & Thomas Adès (Pentatone, 2018)

Bostridge’s involvement with the cycle dates back to 1994 (a video recording with Julius Drake) and another recording with Leif Ove Andsnes a decade later. The 2018 release, live from Wigmore Hall, is filled with honesty and sensitivity (read our review here). The bubbling anticipation in Die Poste (13) is almost uncontainable and Adès’ pristine staccatos only add to this energy. Die Krähe is unusually (and perhaps too) slow but a side-by-side listen with the Andsnes version reveals a fascinating transformation: the narrative quality of the faster-paced version gives way to something much more ominous, especially with the singer’s excellent voice control. In the intense sostenutos, Bostridge has whispery shades that reveal a previously unheard eeriness. Meanwhile, Adès crafts a sad fragility in the way he plays the triplets.

Period Instrument Version

Mark Padmore (tenor) & Kristian Bezuidenhout (Harmonia Mundi, 2018)

This recording is the second for Padmore, who also put out an excellent (modern instrument) version with Paul Lewis on the same label back in 2009. Padmore does have similarities in timbre and approach to Bostridge in the aforementioned recording, but the performance is still unique. Padmore’s light tone gives way to effectively arched phrases and piercing emotion as in Wasserflut (6) or an effervescent excitement in Die Poste (13). Listeners will notice how his voice quality works well with the tone of the period instrument, but this is in large part due to Bezuidenhout’s fine playing. He adds lovely color changes throughout and his touch unveils the piano’s delicate translucence.

Support Us

We hope this guide has helped you navigate the wonderful world of classical music! If you enjoyed this free resource, consider making a donation to The Classic Review. Your generosity helps us keep the music playing by allowing us to publish informative guides, and insightful reviews. Every contribution, big or small, allows us to continue sharing our passion for classical music with readers like you.

Donate Here