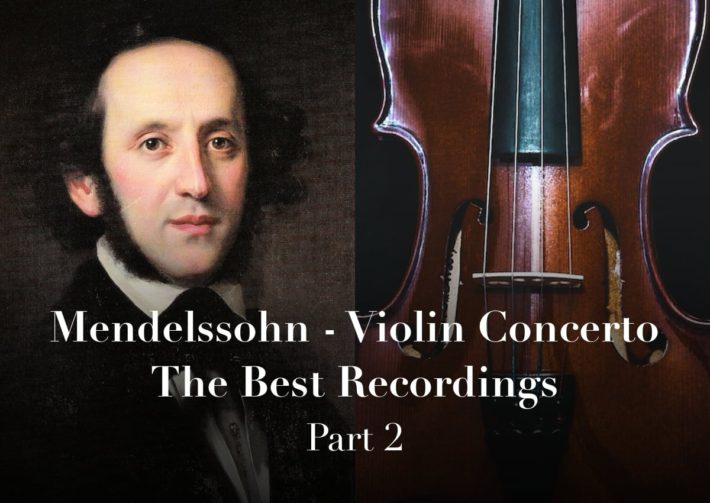

This is the second part of our “Best Of Classical Music Guides“, dedicated to Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto. See below the previous part (Part I):

Part 2

With the beginning of the 1980s, the recording industry saw the transition to digital technology, abandoning the bad audio transfers of the cassettes and slowly fading out vinyl production. The new “Compact Disc” format brought on a wave of new recordings of the entire classical music repertoire including, naturally, the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto. Some violinists re-recorded classical music pieces in a new, often improved audio quality (some of these re-recordings were mentioned in part 1 of this guide). In addition to the technological developments, a new style of playing Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto has emerged, playing with period instruments from Mendelssohn’s days, or incorporating smaller ensembles, more aligned with orchestras sizes the composer was familiar with.

Mendelssohn Violin Concerto – The Digital Era

Even taking into account Anne-Sophie Mutter’s charisma and talent, and there are plenty, this 1980 version is Karajan’s performance, who accompanies the soloist well with the Berlin Philharmonic on top form, but drags the tempos. It’s another one of the many superb collaborations of the two for the yellow label, but this Mendelssohn is not as impressive a performance as their Brahms or Beethoven concertos. In the first movement, for instance, the collaboration is tight, yet Mutter’s intense vibrato can be a bit much.

The slow movement is very reserved and mature, yet one wants a bit more sound from the violinist. And the overly powerful brass of the Karajan era is present here in the climaxes. The third movement is a little heavy and old-fashioned in a bad way, making it sound too serious.

Still, it is one of the best performances from the early 1980s and may satisfy listeners who like their Mendelssohn Violin Concerto broad and a tad heavy, not to mention fans of Mutter, Karajan or the Berlin Philharmonic.

Mutter’s second version with Kurt Masur and the Gewandhause Orchestra (2008), was recorded and marketed for Mendelssohn centenary year. The tempos here are faster, and this is a more relaxed performance and collaboration, with a smaller sound by all parties. The violinist plays wonderfully, but the general feeling is of chilled detachment. The weak point here is the second movement, where the soloist adopts a sound so weak it lacks focus. The muffled recording doesn’t help either. Not one of the best recordings from this tremendously important violinist.

Masur and the Gewandhause Orchestra are much more successful in Maxim Vengerov’s version. The violinist can seem over-enthusiastic at times, his vibrato highly intense in the high notes, but Masur and the orchestra are something of a taming force. The results are often fascinating, combining warmth, excitement and good spirit. Overall, this is one of the more enjoyable performances from the 1990s.

Nigel Kennedy provides a charged, energized performance, sometimes at the expense of refinement and accuracy, especially in the double notes. As always with Kennedy, there are tweaks to the expected phrasing and articulations, like in the second subject of the first movement, nicely played but slow to the point of indulgence. The cadenza is intentionally, well, bizarre.

The slow movement is unsentimental and shows some good playing from orchestra and soloist, but then it goes on to have an on-the-bit feel and loses tension.

The finale is very good indeed, though Kennedy’s playfulness always seems like an act rather than being organic or spontaneous. With all of these shortcomings, this is still a fascinating performance that, at its best, keeps the listeners engaged with this so often heard piece.

“Broad” can summarise Gill Shaham’s approach to the first movement, with a performance that showcases the beauty of his weighty, big sound and the quality of the orchestral accompaniment, yet with a tendency to lose purpose and a sense of direction. The cadenza of the first movement, however, is exquisite. The slow movement is perhaps the highlight of this version, and the third movement, if not exceptional, the partners sound just right in terms of pacing. With a good recording quality, this is a solid version, but standing next to the competition, it is mainly for Shaham’s fans.

Joshua Bell’s two official recordings are both of high quality. The first attempt, with the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields, finds the violinist taking queues from Marriner and the ASMF. His violin sound is precious and the three movements go by in measured tempi and sincere calmness. A lovely performance, even if not a fist choice. And a shame that the 1990 digital recording is not one of Decca’s best.

Bell’s second performance with Roger Norrington and the Camerata Salzburg, recorded more than a decade after his first, is much more persuasive. This is a tight, almost condensed account that nonetheless manages to keep its dynamism. And this recording more successfully catches Bell’s pure tone, as well as his fingerwork. Norrington’s vast experience with period-instruments groups is in evidence, the orchestral balance and phrasing are “historically aware” and sometimes sound experimental, the tuttis a bit bombastic and to-the-bar. This is mainly because of the brass and timpani, which make the first movement feel almost militaristic. The biggest attraction here is the cadenza, not the one commonly used, by a new one impressively written and played by the soloist.

Like Bell’s second performance, Leonidas Kavakos is accompanied by the Camerata Salzburg, but here the orchestra goes to the other extreme, lacking warmth or enthusiasm. As always, Kavakos is an assured, energetic and almost muscular performer. There is an attractive directness to his playing in both main subjects of the first movement, without superficial glissandi one often hears and good control over vibrato. The third movement is severe but impressive technically. The program is generous, with the album including both of the wonderful Piano Trios.

Sara Chang won many praises for her performance with the Berlin Philharmonic and Maris Jansons, but in re-listening to this version next to the many other versions available, many will find her sound in the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto rather weak, with ineffective declarations and vibrato. The Berliners are playing well but the tempo is sluggish. In the outer movement, Chang tends to the over-sentimental, while the slow movement is matter-of-fact and lacks affection.

Midori took some time to record the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, and the result is an energetic performance, full of life and with superb playing by the soloist and the orchestra. The Berliners charge through to the fore when called for, and these moments are part of what makes this collaboration exciting (even if the BPO can sound over-sized at times). The recording quality is superb too.

This version has its weaknesses, though. The cadenza of the first movement is a bit too reflective and grinds the movement to a halt. There is a directness that can be attractive but also a little bit cold, and Midori’s portamento can be too emphasized.

In the second movement, Midori Shows good control over vibrato, but the sound of the violin is thinner and has less presence than on other performances. This is also true to the third movement, when, at times, Midori is having trouble coping with the large orchestra.

Still, no one can deny Midori’s mesmerizing ability to catch the listener, and at its best moments, this is one of the more exciting performances. It lacks some of the extra spirituality that needs for it to be in the top 3 recommendations of the best recording of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, but fans of Midori, rattle and the Berliner Philharmoniker will not want to miss this. General fans of the Concerto will not be disappointed either.

With Ray Chen, the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra and Daniel Harding, we get what can be called a “Mendelssohn Violin Concerto for the 21st century”. This is a very good version; dynamic, energetic with a decent amount of sentimentality and good taste. Certainly, one of the better performances to come out in recent years, and great recording quality to match.

But if one is honest, this performance will not speak to all listeners; it is an especially transparent performance from the orchestra’s standpoint, which is very illuminating but may take listeners aback when expecting a big orchestral sound in the tuttis. The final results, even more than in a period instrument performance, is chamber-like. Also, the second movement is almost banal, and the third movement is so light-hearted, it’s almost Mozartian. After a few careful listening sessions, one notices a lack of final polish, Chen sometimes lacks the final control in his left hand and bow work. All in all, a unique performance that catches the ear for its special approach. For that alone, it is certainly recommendable.

Harding is also the accompanying conductor in Renaud Capuçon’s version, this time a chamber orchestra in size rather than in approach, conducting the Mahler Chamber Orchestra. As a chamber version, it sits in the middle between the period and romantic approaches. The partnership works well, and in general, this is highly enjoyable even if, like in Chen’s excellent account, a bit cold from the orchestra’s side. This is especially true to the strings, which one wishes were a bit bigger in size. That being said, the transparency allows for some marvelous hidden details to come to the fore, and Capuçon’s playing is a delight. The slow movement is flowing with just the right amount of sentimentality and incorporates lovely dialogues with the woodwinds. It’s the strings again that lacks warmth. Highly recommended for the unsentimental listener, then.

James Ehnes belongs to the “well-executed” group of recordings, and it would have been an even greater success if only the violinist had resisted the temptation to move or excite the listener by all means. In the first movement, there are breakouts and accelerations that sound mannered, and in the second subject, there is over usage of rubato. The slow movement is over-sentimental, and the third sounds overly exciting. There is something a bit hysterical about this performance, and a little more restraint could have made this a top tier recommendation. That said, the accompaniment by the Philharmonia Orchestra under Vladimir Ashkenazy is excellent, and the Octet that follows the Concerto is utterly enchanting.

Nemanja Radulovic is a nice surprise, not the most perfect playing in terms of accuracy, intonation or recording, but as always, Radulovic is original and refreshing in everything he does, and the results are a fun and spontaneous live performance. This is an ear-catching version that stands out from the crowd. With so many alternative versions to this Concerto, that in itself amounts to a big achievement.

From the Naxos available versions, Tianwa Yang is probably the most recommended. Her sharp attack and steady tempo choices are very attractive, even if her left hand (especially her vibrato) can become a bit unstable in the dramatic passages. The orchestra (The Sinfonia Finlandia Jyväskylä) is well prepared to take on the accompaniment part, yet is also far from remarkable. Otherwise, like many of this artist’s recordings, a highly enjoyable version, if not a first choice.

For Name’s Sake

As mentioned at the beginning of this guide to the best recording of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, almost every decently known violinist took the time to record this piece. It’s almost surprising, then, that some of the world’s well-known violinists produced performances which were at best mediocre and at their worst, plain bad.

Hillary Hahn gave some lovely performances of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, one of which exists on YouTube. Her studio version is not one of her best efforts for Sony Classical. Accompanied by the conductor-less Oslo Philharmonic, the violinist gives a matter-of-fact, cool as ice, sometimes rushed and, in the slow movement, an intentionally unsentimental performance that fails to make a real impression. Hopefully, there will be a revisit to match her other superb concerto recordings or her live performances of this piece.

Daniel Hope seems to want to stand out from the crowd, but the result is a performance that occupies itself with being special, including superficial romantic gestures and an orchestral accompaniment too punchy and march-like in the tuttis. Like Chouchane Siranossian (see below), Hope incorporates Mendelssohn’s early drafts and some tweaks to the phrasing, but even so, this is not a contender for a top version.

Janine Jansen is yet another soloist accompanied by Mendelssohn’s own orchestra, the Gewandhaus Orchestra, this time under Ricardo Chailly, who made some wonderful recordings by the composer with this ensemble. The opening, though, is not very promising, and there is something rather ordinary compared to other accounts in this review. The violinist’s control of vibrato and bow with a sweet, almost weak tone is simply not on par with the best of violinists (the second subject in the first movement is a good example). Jansen makes the Cadenza of the first movement the focal point of the movement, but the results are too showy. The orchestra and Chailly are doing their best to serve the soloists, and the recording is good, but once again one realizes the vast amount of good versions of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto. This performance just can’t compete with the best.

Nicola Benedetti enjoys a celebrity status of sorts in recent years, but her performance of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto doesn’t meet her own standards, which she amicably displayed on her more recent albums. Her left hand is unstable, her opening too sentimental, something drags in the fast movements and the sound is boomy. The players of the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields under James MacMillan are not at their best either.

Christian Tetzlaff and the Hr-Sunfoniorchesrer under Paavo Järvi present the Concerto with a thin sound, giving too much emphasis when “subito forte” is instructed in the score, an unflattering vibrato and too muscular orchestral playing.

Augustin Hadelich, on the other hand, gives a reasonable performance, which can’t truly stand the comparison with the rest in the vast catalog. For the violinist’s fans mainly.

Going Back In Time

Since the late 1950s, a dedicated group of musicians started performing Baroque music on “period instruments”, using shorter baroque bows and gut strings. A few of the first pioneers in this group were Gustav Leonhardt and Nicolas Harnoncourt. These groups, admittedly, took some time to get used to the old instruments and their initial interest stoped with the music of Bach, Handel, their contemporaries and predecessors. Their big break came with the evolution of the recording industry. The digital era of the 1980s saw major labels adopt the historical practice approach. In the studio, it took around a decade for the period groups to explore nineteenth-century music, but they slowly made recordings that turned out to be truly illuminating. Many violinists of today, in fact, incorporate lessons they learned from the period approach into their interpretations, even when using modern bows and strings, making their playing, as it’s called nowadays, “historically informed’.

In Monica Hugget’s version from the early 1990s, one can hear that using gut strings and short bows may still be uncomfortable: the fast figurations in the cadenza are a good example, the second and third movements are problematic from an intonation standpoint and sound almost sterile. Also, the first movement is overly segmented. However, like many versions incorporating period instruments, there is an attractive clarity, brightness and sincerity to the performance. The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment accompaniment (under Sir Charles Mackerras) is intriguing, with a slightly over-resonant recording.

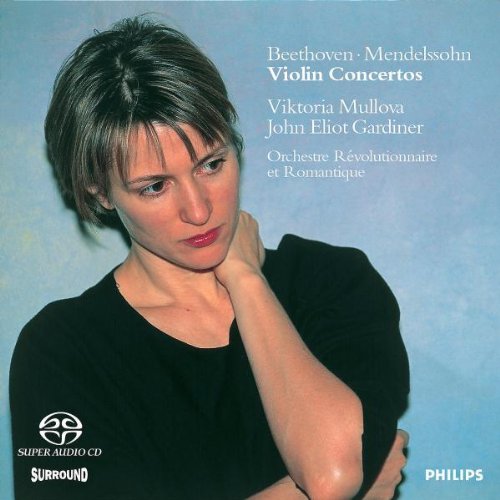

Viktoria Mullova is a violinist that successfully makes a transition between period and modern instruments, playing both equally persuasively. Her earlier set with Neville Marriner and the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields is one of the better performances from the early 1990s, and the ASMIF is on great form. However, Mullova can enter the pantheon of recordings of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto because of her truly illuminating performance on period instruments, with John Eliot Gardiner and the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique (2003). Coupled with a no-less successful performance of Beethoven Violin Concerto, it shines with originality and enthusiasm for the piece. The orchestral accompaniment is transparent yet warm, shading light on not-often heard details in the orchestration and the dialogue with the soloist. Not only is it the best performance on period instruments, but it’s also one of the best versions of the Mendelssohn Violin Concertos out there, period.

One of the more recent attempts at playing Mendelssohn Violin Concerto on period instruments comes from Isabelle Faust, with the Freiburger Barockorchester under Pablo Heras-Casado. Faust seems to do her best to emphasis the qualities of her instrument, with minimal vibrato and a thin, scratching sound in the long phrases. The Freiburg Baroque Orchestra, as we’ve observed in their recent Mendelssohn recording, is too rusty and aggressive, preventing from the Mendelssohnian warmth to come through. Mainly for Faust’s fans, though they too will admit this is not one of her finest recordings.

A lot has changed in the decades that passed form Hugget’s performance to Alina Ibragimova’s version with The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, recorded in 2011. The orchestra is much more comfortable with the instruments, and Ibragimova is a fine soloist indeed. The first movement is nicely done, even if the accelerations in the transitions between themes will raise some eyebrows. Shame that the second movement, as if forcefully trying to keep the tension, sounds rushed, lacking the important serenity needed in this movement. The third movement, on the other hand, sounds a bit rushed. There is something of a gap between orchestra and soloist in terms of sound production; Although Ibragimova uses what sound like gut strings and older bow (this is not specified in the booklet), she plays the instrument with very little “historically informed” practices – allowing for intense vibrato and never limits her dynamic range. The orchestra, on the other hand, is completely immersed in period practices, though less edgy than the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique. As a whole, good as this performance is, extra drama and dynamism are somewhat missing in the outer movements, especially from the orchestra’s side, and the slow movement is clearly preferable in Mullova’s version. Picking between these two impressive period performances goes down to personal taste. An objective qualm does exist, though; This being a Hyperion album, it’s available only as physical or as a single download purchase, costing a monthly subscription price of streaming services. Not a worthwhile buy nowadays.

A year later, Chouchane Siranossian, Anima Eterna Brugge and Jakob Lehmann recorded, on period instruments, the so-called “original version” of the Concerto, essentially using early drafts of the piece, before Mendelssohn took the time to make corrections after hearing the concerto performed several times in public. Like Faust, Siranossian uses the same scratchy sound and adds superficial glissandi that are far from attractive, but the version is at least interesting, getting into Mendelssohn’s early thoughts on the concerto. The highlight of this version, which is far from being a contender, is the third movement, played with real excitement. The Octet that follows is much more successful.

The recommendations

When writing this guide to the best recording of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, I decided to choose three versions which I think give the best possible representation of this masterpiece. Originally, as was possible in the Bach’s Goldberg Variations guide, I thought 2 renown and one “sleeper” version will emerge, but unfortunately, there is no such “sleeper” version which, to me, deserves to be included in a list of best versions. And so, all of the recommended versions are by known artists, which makes the choice even more difficult.

From the old school, mono era, every violinist should listen to Fritz Kreisler’s first version of the Concerto, getting a glimpse into the old Viennese school of violin playing. The same can be said to Joseph Szigeti’s performance from 1933, which shows a cooler side of a great violin-playing tradition. From this era, there are numerous jams, such as Milstein’s 1940’s version, Oistrakh and Kogan. But the big competition (if such exists) from the pre-digital era is between Yehudi Menuhin’s version with the Philharmonia Orchestra under Efrem Kurtz and Jasha Heifetz’s second version with the Boston Philharmonic under Charles Munch. Between the two, Menuhin has the clear edge. His performance of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto has an added spirituality and a truly unique quality of sound, along with a terrific orchestral accompaniment and good stereo recording. All of which makes this not only one of the best recordings of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, but one of the greatest recordings of any piece, on any instrument.

Moving forward, and especially to the digital age, the offering becomes even wider. There are excellent versions for all tastes by all major violinists. An honorable mention must be made for great violinists such as Anne-Sophie Mutter, Nigel Kennedy, Gil Shaham, Maxim Vengerov, Ray Chen and Renaud Capuçon, all presenting highly enjoyable and persuasive accounts of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, versions that will not disappoint either their fans or the concerto. A special nod should be made for Midori’s account with the Berlin Philharmonic and Jansons, which with some weaknesses (mentioned above), it’s still one of the best recordings out there and perhaps the most recommended in a Digital recording.

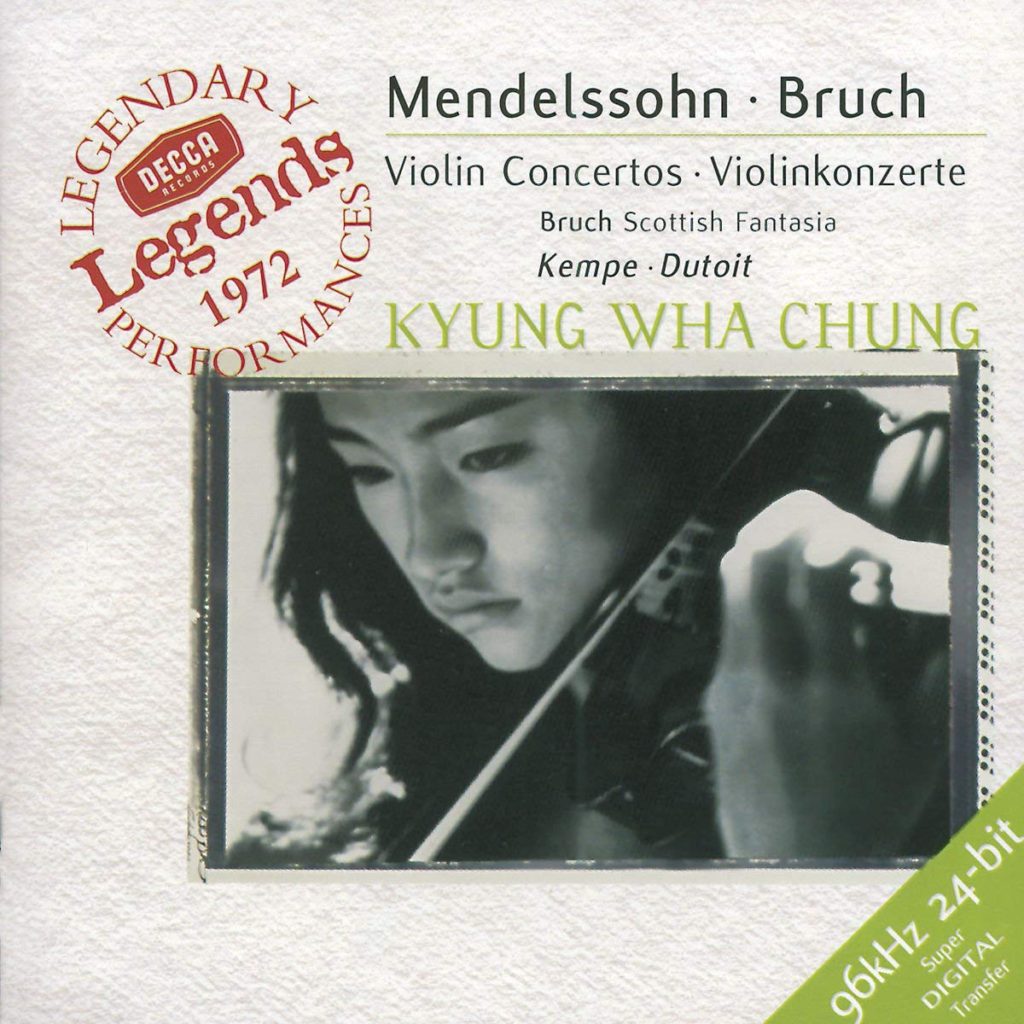

But like Menuhin, it’s actually an analog-stereo version that stands out. When comparing so many performances from this age, no version is more cohesive, energetic and touching than Kyung Wha Chung’s version with Charles Dutoit and the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal. There is a spontaneity coming through from each bar without sacrificing one bit of structural understanding or losing transparency. When hearing this performance, you can’t imagine this Concerto played in any other way, a hallmark of a truly great performance.

Violinists and orchestras have tried performing the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in instruments that were used at the time of the concerto’s premiere, but unfortunately many were less convincing than period performances of music from the Baroque and Classical eras. However, Victoria Mullova enjoys a big success in conveying the fresh look at the Concerto when using gut strings and shorter bows. Together with The Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique and John Eliot Gardiner, Mullova’s performance can be counted among the very best, on period instruments or on modern ones.

So with Menuhin, Chung, Mullova, and Midori, the latter as modern instruments, digital alternative, you are left with the best recordings of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, recordings that will shed the best possible light on this masterpiece. Listeners can then continue and explore the many other excellent performances covered in this guide.

Mendelssohn – Violin Concerto – The Best Recordings

Yehudi Menuhin / Philharmonia / Susskind:

Chung / Montreal / Dutoit

Mullova / ORR / Gardiner

This sums up our guide to Mendelssohn Violin Concerto best recording. Let us know what you think of the choices by joining our social media channels and comment. Join our classical music newsletter to know when our latest classical music reviews and guides are published.