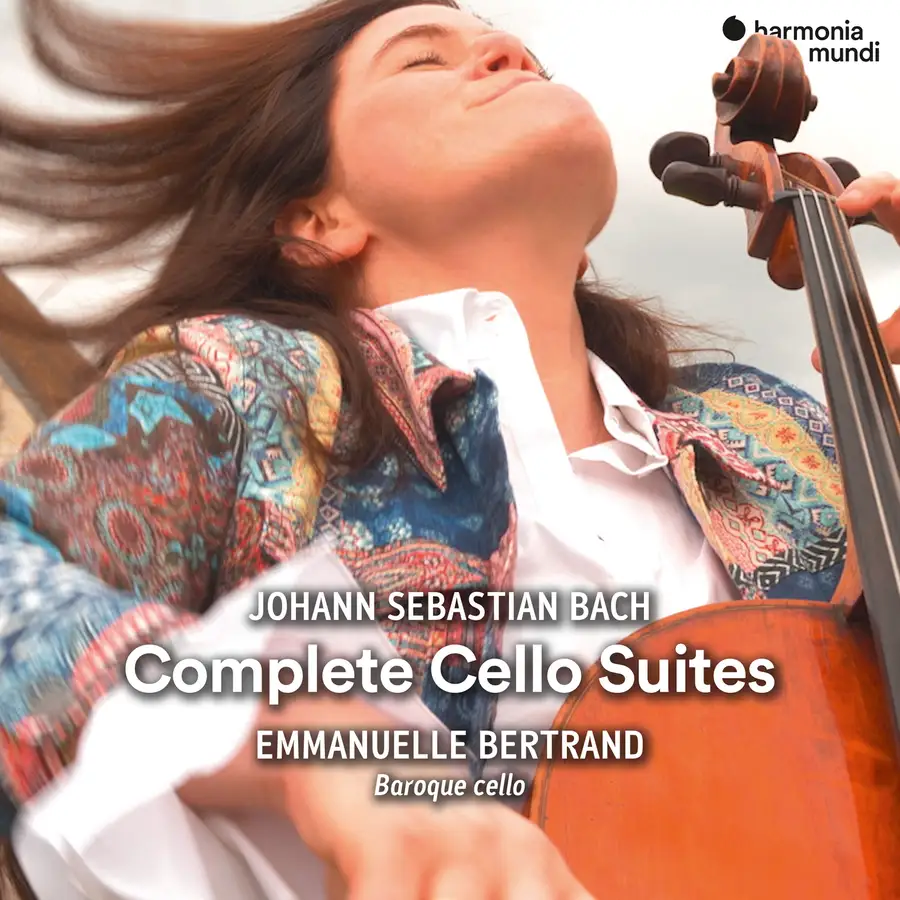

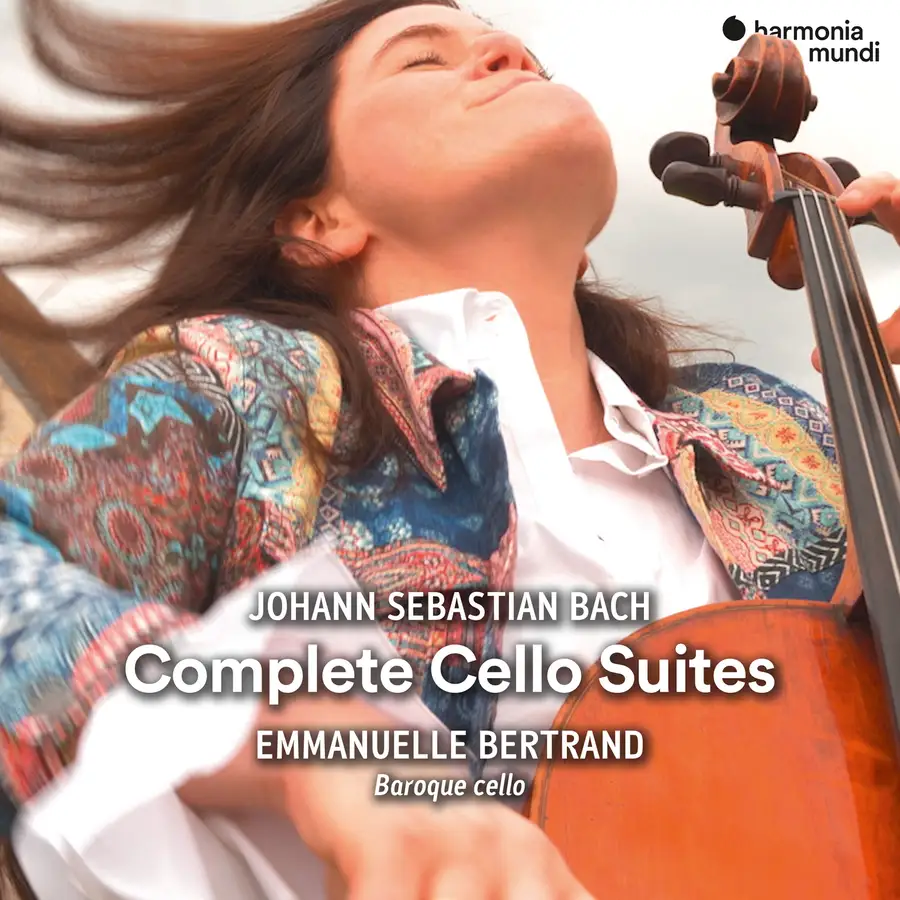

In a crowded market of recordings of the complete Bach Cello Suites, along comes another from Emmanuelle Bertrand (Harmonia Mundi). Hot on the tails of Rachel Podger’s highly acclaimed transcriptions for violin and Yo-Yo Ma’s relatively recent 2018 release (reviewed here), the catalogue brims with recordings from every major cellist of the past 80 years including Paul Tortelier, Mischa Maisky, and Mstislav Rostropovich, but it was thanks to Pablo Casals that these masterpieces were elevated to the pedestal of highly revered jewels of the cello repertoire. Whereas many virtuosi favour the modern cello with its greater resonance, Bertrand performs on a baroque cello. At a lower pitch, with gut strings and an altogether different bow, she creates a lighter sound, still warm, but uniform in colour across the range of the cello with impeccable intonation.

The suites pose a challenge in producing interpretations which are communicative and perceptive whilst balancing the essence of a dance. They require a musician with deep insight into these very introspective pieces, explaining why every cellist sees these works differently. Some focus on the character of the dance, others the prevailing mood. Bertrand takes an expressive approach; these are not to be danced to, they are of the same aesthetic as Waltzes by Chopin — something to be admired, savoured, listened to and reflected upon. Bertrand, like Stephen Isserlis, seems to characterise each suite with a prevailing narrative.

In the First Suite, Bertrand has an evolving, meandering feeling, in which there is a relaxed approach to pulse and rhythm, whilst using some unusual phrasing. The prelude is unassuming, but soon loses its way, lacking climax. In the Sarabande (track 4), the acoustics are used to dramatic effect, but in doing so the impetus is obscured. The Second Suite has an edgy, slightly aggressive quality, achieved through brisker tempos, notably in the Allemande and Courante.

On reaching the Third Suite, the approach is free-spirited, mystical perhaps. Though in the Sarabande (track 16), the rhythmic imprecision hinders the ability to sense the underlying pulse and stateliness. The Fourth Suite, less inhibited by the acoustics, has a similar feel to the First but with greater spirit, the Courante and Bourrées being the most characterful dances (CD 2, tracks 3 and 5). Suite Five is darker, almost foreboding but not making the most of the climaxes. The Sixth has the most dance-like qualities overall, but not always with convincing assurance.

Bertrand achieves a personal reading in this cycle. Throughout, expressive variety is restrained, articulation, homogeneous and dynamically constricted. With her rhythmic freedom, the essence of the dance becomes lost, obscured further by irregular phrasing. David Watkin gives a more sophisticated reading, with all the intrinsic detail and a strong sense of movement of the dance. His tempos vary and diverge from Bertrand’s, but his attention to detail engages to a deeper level. Watkin shows the spectrum of colours which can be achieved on a period instrument, with vivid contrasts, rhythmic vitality and a richness of tone that allow him to capture the essence of each movement.

The booklet includes a warming but brief interview with Bertrand and her journey reconnecting with Bach, which feels personal and sincere. The ambient acoustic of Notre-Dame de Bon Secours (Paris) provides a resonant acoustic and a sense of space for Bertrand’s eighteenth-century cello, built by Carlo Tononi. Recording a solo cello poses many problems for the engineers. On this occasion, they have disappointingly misjudged the distance of the mics with highly noticeable inconsistencies across the album. In the Third Suite in particular, the acoustic becomes overly prominent, blurring the articulation of Bertrand’s playing. There are many audible distractions from Bertrand too. Whilst there is no doubt of her engagement, excessive respiratory sounds become increasingly distracting through the latter suites, the Fifth especially.

Podger’s recording, made on a violin, is a worthy listen for its vision and clarity, peaking appropriately in suite No. 6. The range of the violin brings different textures, which puts a new perspective on these pieces. For a historical recording, it has to be Casals; A modern instrument recording — Isserlis, who’s commanding, considered and perceptive interpretations have a scholarly approach to authenticity. However, for the vibrancy and recording quality, Watkin is the undoubted forerunner of period-instrument performances available.

Bach – Cello Suites, No. 1-6 (Complete)

Emmanuelle Bertrand – Baroque Cello

Harmonia Mundi, CD HMM 902293.94