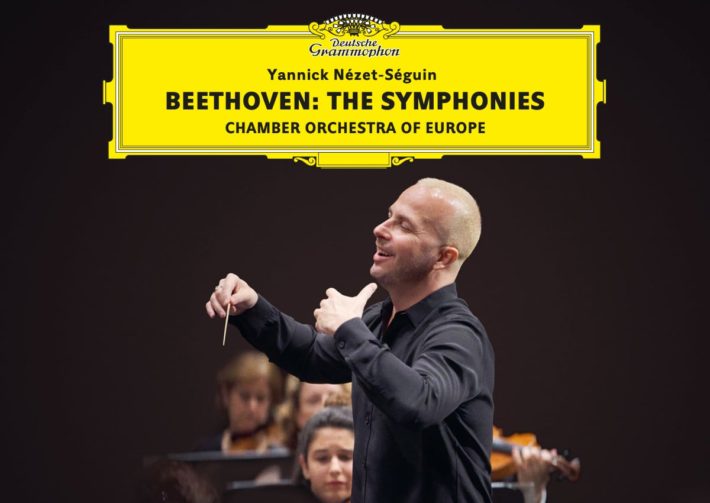

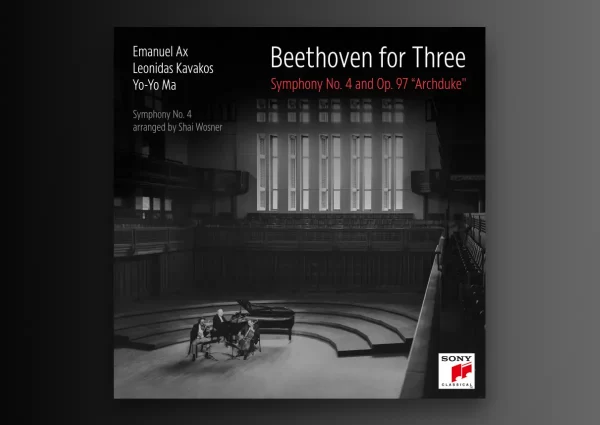

This is the third symphony cycle recorded by these forces, the first two, Schumann and Mendelssohn, were issued in 2014 and 2017. While those are, of course, popular composers, a Beethoven symphony set is another league entirely: no other cycle of symphonies is more recorded and even the list of prime recommendations is overly crowded. And that list includes the fabulous 1990s set featuring this same orchestra led by Nikolas Harnoncourt (Teldec/Warner Classics).

See offers for Beethoven’s Symphonies cycle with the COE and Nézet-Séguin on Amazon.

This latest cycle is unique because it does not use the now standard Bärenreiter/Jonathan Del Mar editions; instead, they play the ‘New Beethoven Complete Edition’ published by G. Henle Verlag. There are few, if any, discernible differences in the first eight symphonies, but in the ninth there are substantial changes: the scherzo is only 559 bars long (versus the normal 954); text underlay is different in the final movement, and a recently re-discovered (and more active) contrabassoon part is used for the first time.

The opening minutes of Symphony No. 1 make it clear that these are historically informed performances, with strings using little, if any, vibrato, and winds balanced well to the fore. Timpani are struck with wooden mallets and the raspy brass colors suggest natural trumpets and horns. Accents have a sharp attack and quick decay; articulation is crisp, and textures are appealingly transparent. Beethoven’s metronome markings are mostly followed. The orchestra’s playing is beyond reproach, and they give their conductor exactly what he wants. And that is where the disappointments set in.

Nézet-Séguin adopts a classical restraint for the first two symphonies that feels a bit like ‘one size fits all.’ Once a tempo is set, he does little to shape phrases or guide the listener through the music’s structure. Look no further than the first symphony’s slow introduction, where Beethoven subverts the listener’s expectations by avoiding the home (tonic) C-major chord. The allegro that follows has an opening theme that uses that missing ‘C’ eight times in the space of four bars. Paavo Jarvi, Savall, and Harnoncourt all shape this music in a way that heightens the subversiveness, but here it is played straight. Nézet-Séguin cultivates playing that is beautiful, cultured and refined. But listen to this same orchestra’s rowdier performance of the second symphony’s scherzo with Harnoncourt, or Rattle’s more raucous reading with the Vienna Philharmonic, and you realize this new performance is slightly under characterized.

The Eroica is more successful. The first movement, played at Beethoven’s metronome marking, is athletic and propulsive, building to an impressive final climax. Nézet-Séguin then sets a slower than marked tempo for the funeral march, using the extra time to highlight a wealth of detail. The Scherzo’s disruptive elements are underplayed compared to Gardiner and Savall, who truly understand how radical this music can sound, but the final movement has an unbridled energy in which each variation tellingly shaped.The less overtly ‘emotional’ fourth symphony receives a spick-and-span performance that treads lightly, highlighting the sunny aspects of the score at the expense of its darker moments. But the playing is thrilling, especially in the final movement. And Nézet-Séguin ensures the first movement of the fifth has a manic, desperate energy. But the second movement is significantly slower than the metronome marking, robbing the music of its expressive power. The scherzo is also too slow, so that when the trio’s fugue becomes lyrical – turn to Savall, or especially Gardiner in his second, live reading, and the same passage evokes terrifying anger. The final movement (note that Beethoven’s metronome indication is honored) brings a return to form, the playing and interpretation thrilling.

Autopilot music making returns in the sixth’s opening movement: every ‘I’ is dotted, every ‘T’ crossed, but phrasing is four-square, and the movement’s climax (10’39”) goes for naught, especially compared to Mackerras (his second cycle) where the climax brings a rush of emotional adrenaline. Mackerras’ reading is especially insightful, phrasing more pliable, the music shaped with unerring grace and a sure sense of architecture. His village folk are rowdier, his storm more threatening than what we hear in this new performance.

The seventh receives the strongest performance in this series: its first movement has balletic grace, and the second movement is sweetly sung. The scherzo is powerful drive with a trio that builds to a potent climax, growing more powerful with each reappearance. The final movement has propulsion and a breathless excitement that rivals, but does not best, Harnoncourt. The horns need to ring out more and the orchestral bass line lacks the Teutonic weight heard in the Harnoncourt and Savall recordings, and this is music that requires that weight.

The eight is another fine performance, the winds perky, especially in the second movement. Nézet-Séguin’s mastery of the music’s many quick-silver mood changes is excellent, as is his voicing and management of color in the ‘Menuetto.’ The fourth movement is graceful and beguilingly articulated, but the forward momentum stalls and those intrusive C-sharps should be more intrusive. The bass is again too light.

Having mostly followed Beethoven’s metronome indications in the first eight, the ninth’s 15’34” first movement comes as a surprise, compared to Krivine’s 14’29” and Gardiner’s 13’05. More distressingly, the music’s angst is mostly unrealized. If the tempo is slower because Nézet-Séguin views this as the first Romantic-period symphony, shouldn’t the emotional import of the music be heightened (as it is in Rattle’s similarly conceived Vienna reading)? The second movement is thrillingly paced, but listeners will be brought up short by those ‘missing’ 395 measures. The Adagio, again under tempo, is songful and beautifully judged, but the finale disappoints, mostly because of the singing. The soloists have pronounced vibratos that do not blend (the initial bass entrance is more wobble than pitch) and a choir lacks heft. This is a festive and joyful reading, but Harnoncourt, Mackerras and Savall all find greater transcendence.

The engineered sound is clinically clear but lacks true front to back perspective and bass. Beata Angelika Kraus’s notes are erudite, but focus almost entirely on the ninth symphony, perhaps indicating that DG believes this set will only be purchased by knowledgeable enthusiasts. (Would it not be better to hope that this charismatic young conductor might entice first-time listeners to these works?)

In the press release for this recording Nézet-Séguin states, ‘I am interested in how Beethoven’s music can surprise us today. Our interpretation should feel to the audience as if they are hearing this music for the first time. That is my goal.’ And therein lies the problem – here the goal is only fitfully achieved, whereas the cycles by Gardiner, Jarvi, Krivine, Mackerras and Savall are far more successful in revealing the revolutionary brilliance of these masterworks.

Beethoven – Complete Symphonies

Chamber Orchestra of Europe

Yannick Nézet-Séguin – Conductor

Deutsche Grammophon, CD DG 4863050

See offers for Beethoven’s Symphonies cycle with the COE and Nézet-Séguin on Amazon.

Recommended Comparisons

Harnoncourt | Savall | Gardiner | Mackerras

Included with an Apple Music subscription:

Latest Classical Music Posts

Read more classical music reviews or visit The Classic Review Amazon store

Follow Us and Comment:

Get our periodic classical music newsletter with our recent reviews, news and beginners guides.

We respect your privacy.