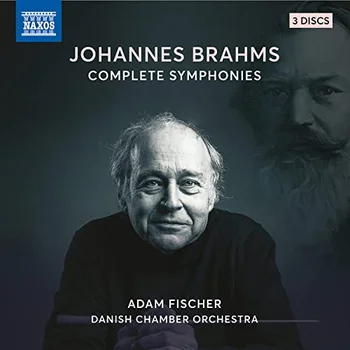

Ádám Fischer’s distinguished career includes several recorded symphony cycles. He is one of the few to have recorded all the Haydn symphonies, and in the last decade we have had Mozart and Beethoven cycles, both with the Danish Chamber Orchestra (DaCapo and Naxos respectively). More recently there was an impressive Mahler cycle with the Düsseldorf Symphony and now this latest series, again with the Danish Chamber Orchestra, released in celebration of this partnership’s twenty-fifth anniversary.

The first symphony‘s opening crackles with energy, the timpani creating propulsive momentum. Orchestral sound is rich, colorful, but lean – the Danish Chamber Orchestra will not be mistaken for their Berlin or Vienna colleagues. But their leanness lets us hear every nuance of the music. The first movement Allegro (2’15”) will strike some as too fast, but it never sounds rushed, and Fischer brings a pleasing elasticity to the phrasing. At 4’34” he lengthens rests, disrupting the rhythm and forward drive. It happens again in the exposition repeat, the recapitulation (12’46”) and, most distressingly, right after the main climax (13’30”). The ineffectiveness of this oddity stands out because the rest of the interpretation is so convincingly right.

Both inner movements are fetchingly characterized, with lithe shaping and lovely solos from the first desks. While Fischer’s music making embraces historically ideas about tempos, phrasing, and orchestral size, he is never dogmatic and brings a romantic expressiveness to his readings. While the final movement’s opening Adagio lack the sheer weight of sound one would find in Berlin and Vienna (or from his brother’s Budapest Festival Orchestra), the Danish players still vividly convey its spooky, forsaken atmosphere. The “Beethoven’s tenth” theme that begins the Allegro proper is subtly voiced, the winningly articulated string and wind dialogue that follows exposing the intimate communication within the orchestra. Voicing is superbly managed, ensuring every textural detail of the development is clearly heard. The coda is taken at a crackling pace, the return of the chorale theme resplendent, the closing minute thrilling in its dynamism and athletic power.

Some conductors view the second symphony as consistently sunny, while others (including Fischer) explore its darker undertones. Fisher does so with great subtlety and unerring judgment, inspiring a lovely sotto voce quality to the opening of the second movement. The wistfully delicate colors of the winds in the third movement are markedly touching, while the final movement has a breathless excitement, its brass-capped coda dispatched with infectious verve.

Even the finest Brahms interpreters struggle with the third symphony, but Fischer’s way is compelling. He plays it straight, allowing us to relish Brahms autumnal colors, winds again especially beguiling. Dynamic control is masterful – one notes the distinct difference between piano and pianissimo. The second movement is another example of ravishing playing, where one sense the players really understand how their parts interact – an excellent example of the special rapport between conductor and orchestra. String sound in the third movement is undeniably less voluptuous than in recordings by Karajan and Wand. Instead, there is a touching fragility, made more affecting by Fischer’s perfectly judged rubato and phrasing. The driven final movement is exhilarating without ever sounding rushed. Fischer’s sure sense of architecture ensures we move through that excitement to the calm serenity at the close.

Unfortunately, the tempos for the first two movements of the fourth feel too quick. Mackerras (Scottish Chamber Orchestra), Paavo Jarvi (Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen) and Dausgaard (Swedish Chamber Orchestra) take more time, allowing for more exploration of the music’s complex web of emotions. The third movement is also quite fast, but feels rather rigorous and dour, whereas Honeck’s recent Pittsburgh performance has a joy de vivre that few, if any, match. The finale brings a return to form, each variation lovingly shaped with scrupulous attention to detail. Variation twelve’s flute solo is achingly tender, as is the trombones intonation of the chorale two variations later. Fischer and his players steadily ratchet up tension through each section, leading to the terrible brass pronouncement at 8’07” that then propels the music headlong towards its final destruction.

Naxos engineering captures the orchestra’s sound with good front to back perspective and a large dynamic range. Liner notes are short but informative and include an interview with Fischer in which he discusses not only the symphonies but his career and work with the Danish ensemble. There are several chamber orchestra, historically informed cycles on modern instruments: one of the first, featuring Charles Mackerras and the Scottish Chamber Orchestra on the now defunct Telarc label, remains especially impressive for connecting period manners with a romantic spirit. Paavo Jarvi in Bremen is also impressive, though his interpretive is more objective, as is Dausgaard in Sweden. The Danish orchestra plays with a sophistication and intelligence that more than matches these earlier cycles, though it is important to note that the Telarc and BIS recordings offer more music: Mackerras includes the Academic Festival Overture as well as the Haydn Variations, while Dausgaard includes the Tragic Overture, Hungarian Dances, and an orchestral versions of the Liebeslieder Waltzes. I wish Naxos and Fischer would have included, at the very least, both overtures. BIS recently released the Dausgaard cycle as a box set costing only a few more dollars than this new release. Nevertheless, Fischer and his Danish orchestra offer a thrilling new series that all Brahms lovers should hear.

Recommended Comparisons

Karajan | Mackerras | Jarvi | Wand

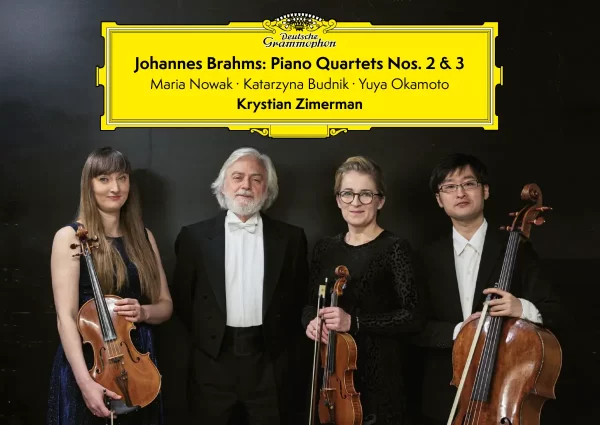

Brahms – Complete Symphonies

Danish Chamber Orchestra

Ádám Fischer – Conductor

Naxos, CD 8574465-67