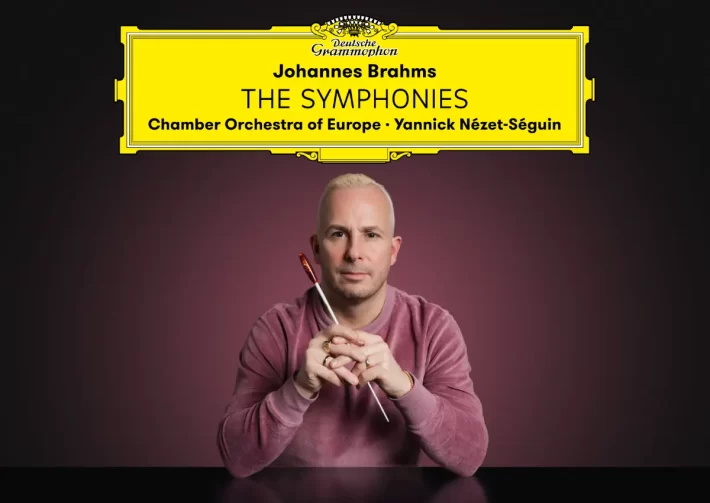

Recordings of the Brahms symphonies performed by smaller forces began with Charles Mackerras (SCO/Telarc) in 1997, followed in 2000 by Paavo Berglund leading the Chamber Orchestra of Europe at the Baden-Baden Festival. Without including period instrument performances (which tend to use smaller forces) we have had ‘chamber-sized’ recordings by Thomas Dausgaard (SCO/BIS – Review), Paavo Järvi (Bremen/RCA), Robin Ticciati (SCO/Linn), and Ádám Fischer (DCO/Naxos – Review). The Chamber Orchestra of Europe, led by Nézet-Séguin, has recorded its second cycle, again recorded live (in 2022 and 2023) at the Baden-Baden festival.

A consistent joy of this set is the COE’s more accomplished playing, an intoxicating combination of rich colors and lithe precision. Nézet-Séguin’s tempos are on the quick side, yet the orchestra is with him every step of the way. Woodwind solos are uniformly excellent, as are Brahms’ beloved horns. Vibrato is used more often than the other recordings listed above, and there is considerable weight and lushness to the orchestral sound, a quality often lacking in chamber-sized performances.

In the first symphony, Nézet-Séguin sets a quick pace for the introduction (dotted quarter = 51), pounding timpani kept in check. But when the music becomes more lyrical, he shifts to a significantly slower tempo. The reappearance of those throbbing eighth notes in the basses returns to the initial tempo, but he again slows down significantly in the following passage. Yes, there should be rubato, but these shifts are unconvincingly extreme. The Allegro is driven hard; again, the tempo relaxes for the second subject, but in a far more organic and subtle way. The string section digs vigorously into its lines, answered by characterful woodwinds and powerful brass. The main climax, while well-prepared, lacks the destructive force that makes the older Karajan and Jochum recordings so affecting.

While the Andante sostenuto is undeniably beautiful, it is overly manicured and fussed over; the music’s lightness is lost. But things snap into place for the third movement: Nézet-Séguin offers fewer interpretative interventions, and the playing is marvelous. The opening of the Finale lacks mystery, but the Allegro’s main theme is beautifully sung (though the sound is less robust than with Karajan and Jochum), and the Coda features excitingly breathless tempos that build to a thrilling peroration.

The reading of the second symphony is excellent, the opening of the first movement lovingly shaped without becoming overly precious. The COE’s energy and finesse are hugely enjoyable, and we hear plenty of inner detail. The finale goes at a brisk pace (shades of Kleiber and Karajan’s 1970s cycle), yet everything is balanced and transparent, the music’s rambunctious energy fully conveyed.

Nézet-Séguin has the measure of the third symphony. The first movement is definitely ‘con brio’ but not overly aggressive (as in Gardiner’s reading on SDG). Dausgaard is even faster and perhaps more bracing, with a bit more Nordic frost. Nézet-Séguin is warmer, his phrasing more supple. He avoids micro-managing and ensures an ever-increasing sense of tension as the movement progresses. The movements are genuinely emotional: after some initial fussiness, the second movement attains a chaste tenderness, answered by an introverted and vulnerable third movement. The closing Allegro is forceful, and eloquent in turn, with playing that is precise and alive. After an exciting final climax, the closing pages are particularly gentle.

Join The Classical Newsletter

Get weekly updates from The Classic Review delivered straight to your inbox.

he fourth symphony is also impressive. If it lacks the last bit of imagination and individuality that makes the classic Kleiber (VPO/DG) and recent Honeck (PSO/Reference – review) so compelling, it comes close. Interestingly, Nézet-Séguin seems to view thus symphony as two distinct parts (there is hardly any space between the first and second movements and the same holds between movements three and four). I admire how the first movement grows from its first tentative entrance to become more impassioned; the delicate filigree of the second movement is answered by the jovial earthiness of the third. The final movement’s variations are characterful (the flute solo, played by Clara Andrada, is exceptionally beautiful), leading into a ferocious nihilistic coda.

DG’s engineering serves the music and the performances well. The liner notes offer little discussion of the music, instead dwelling on Brahms’ time spent in Baden-Baden. I was somewhat disappointed by this partnership’s Beethoven cycle, but find the music-making here considerably more impressive.

Recommended Comparisons:

Jochum | Karajan | Honeck | Chailly

Brahms – Symphonies No. 1-4

Chamber Orchestra of Europe

Yannick Nézet-Séguin – Conductor

Check offers of this album on Amazon Music.

Album Details |

|

|---|---|

| Album name | Brahms – The Symphonies |

| Label | Deutsche Grammophon |

| Catalogue No. | 4866000 |

| Amazon Music link | Stream here |

| Apple Music link | Stream here |