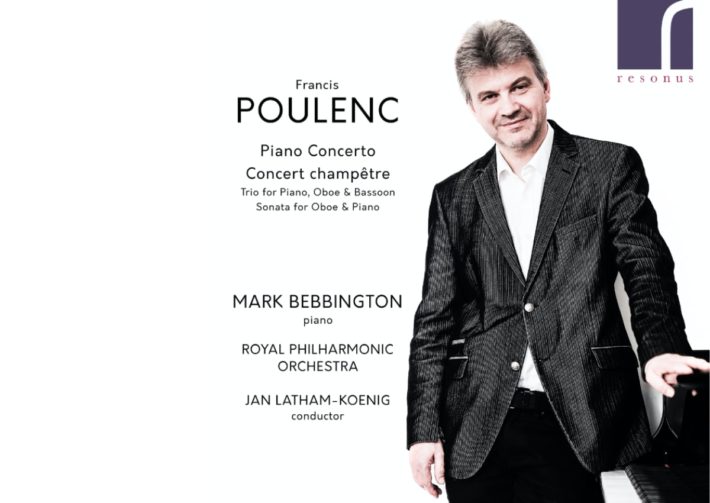

Mark Bebbington and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra are in fine form on this album of Poulenc piano works, including both his Piano Concerto and his Concert Champêtre (originally for harpsichord, here with piano). Jan Lathan-Koenig conducts, as he did in 2018 when this same cast performed Grieg and Delius. The album also includes two Poulenc chamber pieces, the Trio for Oboe, Bassoon, and Piano, and the Sonata for Oboe and Piano, which contrast wonderfully with the concertos.

Bebbington and the orchestra expertly create the mélange of musical styles and moods in the Piano Concerto. In the Allegretto, the opening is dark and cool, and yet the entire group is playing a unified molto legato; it’s a stunning, sophisticated effect. Later, where the orchestra mimics or plays with Bebbington, they match his articulation (kudos to the oboe and piccolo, for example, at 3’40”). The brass arise from Bebbington’s block chords with unusual serenity and force, almost à la Copland (many times, first at 5’55”). The Andante sees Bebbington mostly punctuating the orchestra’s melody, but where he does take over, he has all the delicacy required; pianos can’t slur, but on those melodic falling 6ths and 7ths, it sure feels like they can. The final Rondeau is not a particularly virtuosic or serious piano part, so the drama mostly comes from the juxtaposition of theme and episodes. Bebbington and the RPO are up to the task, mostly comical (have you ever heard faster grace notes in the theme?), sometimes feigning distress (3’11”) or seeming to swoon (2’48”), always unified in their interpretation.

The Piano Concerto dates from later in Poulenc’s life (1950), so it seems fitting that Bebbington has bookended it with the Oboe Sonata, Poulenc’s final completed composition (1962). It’s a treat to hear Bebbington play the Oboe Sonata, as he brings out all the part’s subtleties. A great example is at 1’48” in the first movement (track 10), where he brings out middle voices alternating first between a major and minor 7th, and then between a major and minor 3rd. Another is the repeated eighth-note figure that announces the Scherzo, where he brings out the differences the second time it appears (3’03”; differences, by the way, which were lost due to an editing error for many years). Throughout, Bebbington is in total command of the piano’s texture, and his sense of rubato is stronger than most accompanists who play this piece. Deserving of equal praise is oboist John Roberts, who sounds absolutely ravishing. His vibrato is complex and mature, adopting different speeds as appropriate. I felt a real sense of personal reminiscence and occasional anger in the Elegy. The tricky second movement is totally controlled, but it loses no excitement. In the third movement, a mourning song that spans the oboe’s entire range, Roberts’ high Eb and low Bb are equally sonorous and enchanting.

Related Classical Music Reviews

- Review: “L’Album des Six” – Corinna Simon, Piano

- Review: Fauré – Requiem, Poulenc – Figure Humaine, Les Siècles, Ensemble Aedes, Romano

- Review: Bartók – Concerto for Orchestra, Suite No. 1 – Dausgaard

The other two pieces on the album, the Trio and the Concerto Champêtre (for harpsichord), date from earlier in Poulenc’s life. The Trio is comparatively generic, though bassoonist Jonathan Davies joins Bebbington and Roberts for a jolly rendition. The Concerto Champêtre, on the other hand, is quintessential neoclassical. Poulenc often performed the Concerto himself on modern pianos, so Bebbington is in good company here. Unlike Bach’s harpsichord concertos (and many others), the piece doesn’t suffer because of it — in fact, many will actually prefer it. Bebbington pays homage to the harpsichord by eschewing the sustain pedal, but in other places takes advantage of the modern instrument. For example, in the first movement’s opening, Stravinsky-esque chorale, he’s banging away; when the main theme appears, reminiscent of Schumann’s Happy Farmer, there’s a playful touch; and when the Rite of Spring exerts its influence (3’50”), suddenly the piano is hushed and legato. The harpsichord version feels bland in comparison, despite the crackly tone. A good choice for comparison is Anima Eterna’s 2008 recording with Kateřina Chroboková. In the Andante, Anima Eterna’s period strings play non-vibrato; this, too, saps the piece of lots of color. RPO’s strings have depth without overt romance. In the rollicking finale, the color in Bebbington’s playing feels indispensable.

This album feels much longer than 72 minutes, in a good way – it’s got four complex and beautifully performed pieces of music, demonstrative of Poulenc’s many facets. The recording quality is superb throughout. This is surely one of the all-around best albums of Poulenc in a while.

Poulenc

Piano Concerto, FP 146

Concert Champêtre, FP 49

Trio for Piano, Oboe & Bassoon, FP 43

Sonata for Oboe & Piano, FP 185

Mark Bebbington – Piano

John Roberts – Oboe

Jonathan Davies – Bassoon

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Jan Latham-Koenig – Conductor

Resonus, CD RES10256

Recommended Comparisons

Read more classical music reviews or visit The Classic Review Amazon store

Follow Us and Comment:

Get our periodic classical music newsletter with our recent reviews, news and beginners guides.

We respect your privacy.