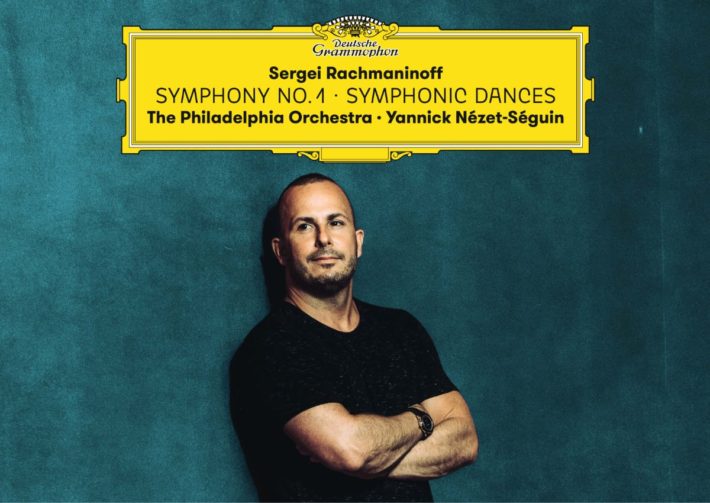

The Philadelphia Orchestra has a long and illustrious history with Rachmaninoff. He recorded his piano concertos with the orchestra, and the only recording with Rachmaninoff conducting also features the Philadelphians playing his third symphony, the tone poem “Isle of but superficial Dead” and “Vocalise.” Eugene Ormandy’s pioneering cycle of the symphonies, recorded in the 1960s, remains a reference recording for many collectors.

In the 1990s, Decca recorded a new symphony cycle with the Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by their principal guest conductor at the time, Charles Dutoit. The cycle was not well received: Dutoit’s interpretations were glitzy but superficial, and the recorded sound was often muddy and poorly balanced.

More recently, DG recorded the piano concertos and Paganini Rhapsody, played by Daniil Trifonov and the Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by Nézet-Séguin. The recordings were widely acclaimed (including in these pages – see here and here), so it seems only natural that these same forces would now turn their attention to the symphonies.

The premiere of Rachmaninoff’s “Symphony No. 1” on 28 March 1897 was a dismal failure. The criticism was savage, and soon after Rachmaninoff had a complete emotional breakdown and was unable to compose anything for the next three years. (Much of the blame for the premiere’s failure lays with the conductor, Alexander Glazunov, who was inebriated while conducting.) Certainly, this new performance, recorded live in June 2019, shows how wrong those first critics were.

Related Classical Music Reviews

- Review: “Destination Rachmaninov – Departure” – Piano Concertos No. 2 & 4 – Daniil Trifonov, The Philadelphia Orchestra, Yannick Nézet-Séguin

- Review: “Destination Rachmaninov – Arrival” – Piano Concertos No. 1 & 3 – Daniil Trifonov

- Review: Mahler – Symphony No. 8 – Philadelphia Orchestra, Yannick Nézet-Séguin

The opening measures immediately command attention, snarling brass answered by fearsome string pronouncements. The mood then changes as Seguin sets an ideal Allegro tempo for the Exposition, the playing lithe and precise, every change in color and texture ideally realized. And for anyone doubting that the current orchestra can call up the famous “fabulous Philadelphia” sound so well-known from the Ormandy era, sample the burnished warmth of the strings beginning at 2’38” – answered by equally beguiling winds.

Orchestral balance is superb, allowing us to follow every voice in Rachmaninoff’s polyphony. Climaxes are masterfully built and the virtuosic writing is brilliantly played. What most impresses is how beautifully Séguin shapes softer passages, allowing his players plenty of room for individual and sectional expression. His rubato in the slow movement allows for many moments of almost improvisatory freedom, while at other moments (such as 2’13”, track 3) he makes the exchange between the solo winds and strings a gentle, intimate dialogue that is genuinely touching.

The final movement is dispatched with imposing bravado, the orchestra conjuring up a Slavic weightiness as the music falls into ever deepening despair. The tam-tam hit at 10’37” has a visceral impact, and Séguin rightly keeps the coda moving, so that the finals bars suggest a march to the death, capped off by two mighty hammer chords that leave the listener spent.

“Symphonic Dances,” Rachmaninoff’s last orchestral work, was written for, and dedicated to, Ormandy and the orchestra. Ormandy’s premiere recording is one of the best he ever made, though the sound is inevitably dated. Séguin’s account is noteworthy for the variety of color he draws out of his players – the big tunes and climaxes have all the rich voluptuousness and weight one could want, but he also finds a myriad of subtler hues in this music. And these performers never forget that this music was originally intended for a ballet – even when the music is at its most raucous, it dances. In the first movement (track 4, 3’03”) listen to how sensitively the winds shape their phrases, creating a poignant atmosphere for the saxophone’s tender elegy. Again and again, the Philadelphia woodwinds play with the intimacy and connectedness of chamber musicians.

In the second movement, Séguin again offers generous rubato, allowing the Philadelphia players time to create some ravishing colors and dialogues. The final movement, played with stunning virtuosity, is particularly overwhelming in the final three minutes: as the music reaches its climatic peak (11’31”) the trumpets blast out the Dies Irae theme (which haunts so much of Rachmaninoff’s music), suggesting this music will, like the first symphony, end in defeated sadness. But at 12’58”, as the orchestra quotes from the composer’s All-Night Vigil, his setting of the words “Blessed be the Lord”, the music turns away from darkness, the final 18 bars serving as a joyful “Hallelujah,” the final tam-tam stroke allowed to reverberate after the final chord.

DG’s recording faithfully captures the orchestral sound of Verizon Hall. Chemistry between orchestra and conductor is palpable, adding another layer of intensity and passion to these exceptional performances. Let us hope that the next two recordings are as successful as this one – urgently recommended.

Rachmaninoff – Symphony No. 1, Symphonic Dances

Philadelphia Orchestra

Yannick Nézet-Séguin – Conductor

Rachmaninoff Symphony 1, Symphonic Dance – Recommended Comparisons:

Read more classical music reviews or visit The Classic Review Amazon store

Follow Us and Comment:

Get our periodic classical music newsletter with our recent reviews, news and beginners guides.

We respect your privacy.