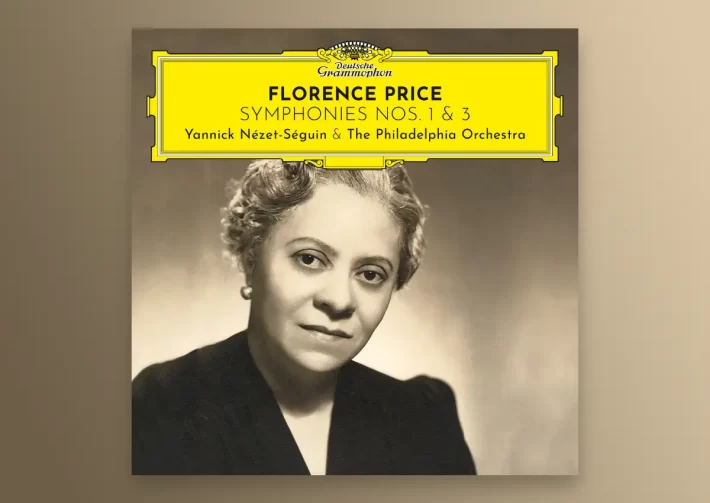

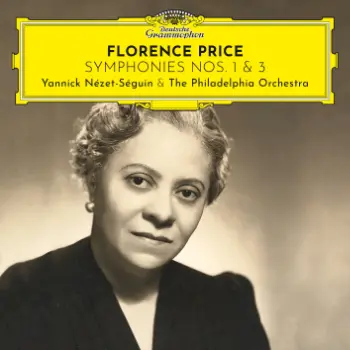

I first heard the music of Florence Price on a recording by the New Black Music Repertoire Ensemble conducted by Leslie B. Dunner (Albany Records, now available as a digital download). Both works on that album (Symphony No. 1 and Concerto in One Movement) clearly reveal American pedigree without becoming derivative or mere pastiche. Her melodies demonstrate the influence of folk tunes and spirituals; orchestral textures, especially in the slow movements, remind us that she was an accomplished organist. The oft-times sophisticated harmonies embrace chords from the world of jazz and the blues. Yet Price has a distinctly unique and accomplished voice.

See offers for Beethoven’s Symphonies cycle with the COE and Nézet-Séguin on Amazon.

The newfound recognition of her music over the past few years has, of course, led to push back from certain critics, their two main points being that her music is derivative and at times overly long (an argument long lobbied against Bruckner, though today few would dare suggest such a thing). The first argument quickly moves into uncomfortable areas, especially in America. It is undeniable that the first symphony reminds every listener of Dvorak’s last symphony. But to suggest that a black women who grew up in Arkansas is copying the Czech composer by composing melodies that reflect Native American and African American music is dubious reasoning. Best then, to let the music speak for itself. And surely Price would be pleased to hear her music played by one of American’s finest orchestras on a recording produced by one of classical music’s preeminent labels.

As noted, Price’s first symphony lives in the same sound world as Dvorak’s ninth. And yet Price’s writing wanders down different harmonic paths. Melodies are inherently vocal (a quality she shares with Mozart and Schubert), and are played here with unanimous precision, great beauty, and palpable enthusiasm. Listen to how magnificently the Philadelphians transition to the slower secondary material (track 1, 2’08”) – a series of short melodic exchanges in the winds that lead to an extended melancholic horn solo, accompanied by richly burnished string chords. The remainder of the movement becomes a struggle between the optimism of the opening and the second theme’s gloomier emotions.

Both slow movements remind us that Price was an accomplished organist. With more homophonic textures, Price often shifts from one instrumental family to another, much as an organist might switch from manual to another, while the slower harmonic motion suggests church hymns. There are several wind solos where one imagines Price, up in the organ loft, suddenly improvising a virtuosic melodic flourish. Nézet-Séguin provides his solo players plenty of room for rubato and exhibits a masterful sense of the long line and the music’s architecture, surely a benefit of his experience conducting Bruckner. If forced to choose one movement from this recording to play for a first-time listener, it would be the slow movement of the third symphony (track 6), which features one beautiful melody after another, accompanied by a kaleidoscope of orchestral hues (played here with rapt introspection) that are profoundly touching.

Price’s most original idea may be the replacement of the expected third-movement scherzo with a “Juba Dance.” Created by slaves who were denied the use of percussion instruments by plantation owners, the dance’s rhythms are made by slapping the arms, legs, and chests. As heard here (tracks 3 and 7) the movements quickly become rambunctious celebrations featuring driving rhythms, and ever-shifting orchestral colors. And the joy of this music carries over into the final movements, both of which feature dancing compound meter that steadily builds into riotous and exuberant codas.

These symphonies are available on two different Naxos albums: the first played by the Fort Smith Symphony and the fourth by the ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra. Both are conducted by John Jeter, who leads excellent and committed performances of both works. Naxos’ deep and wide soundstage (especially for the third symphony) allows the listener to hear every strand of Price’s wonderful orchestration. Nevertheless, the Philadelphia Orchestra is the finer orchestra, with a more sophisticated tonal palette. The many wind solos are beautifully played and the orchestra at full cry is thrilling. DG’s recording may prove a bit boomy for some, but I didn’t find it bothersome. The Philadelphia strings have their expected sheen and warmth.

Most importantly, Nézet-Séguin clearly believes in and loves this music, and that passion is clearly manifested in the orchestral response. If forced to choose only one recording, this would be my primary recommendation. But this is music worthy of multiple recordings and owning both gives the listener greater insight into and appreciation for Price’s wonderful music.

Florence Price: Symphonies Nos. 1 & 3

The Philadelphia Orchestra

Yannick Nézet-Séguin – Conductor

Deutsche Grammophon, CD 4862029

See offers for Beethoven’s Symphonies cycle with the COE and Nézet-Séguin on Amazon.

Included with an Apple Music subscription:

Latest Classical Music Posts

Read more classical music reviews or visit The Classic Review Amazon store

Follow Us and Comment:

[social_icons_group id=”964″]

[wd_hustle id=”HustlePostEmbed” type=”embedded”]