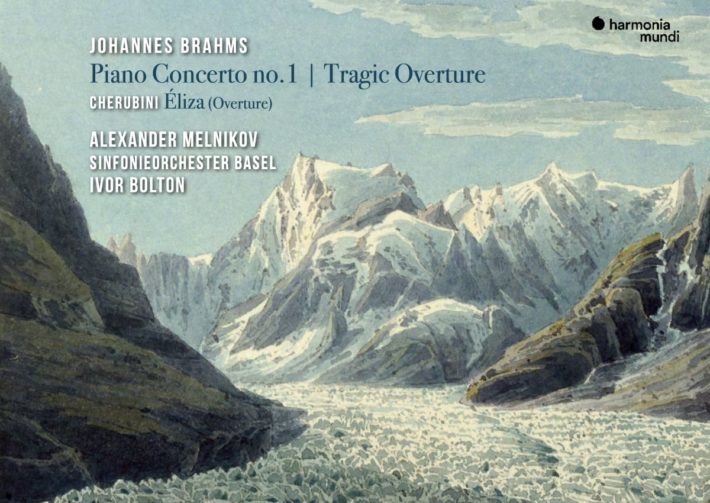

Pianist Alexander Melnikov’s catalogue of recordings embraces a wide variety of solo, chamber and concerto repertoire. Thus far, Brahms is only represented by a recording of the second and third Violin Sonatas with Isabelle Faust. It is therefore particularly exciting to hear this gifted player tackle Brahms’ challenging first Piano Concerto.

The album beings with a disappointingly stodgy and ill-conceived reading of the “Tragic Overture.” Bolton’s tempo is the slowest I know, and it feels even slower. While orchestral balance and color is excellent, the sound lacks heft. More distressingly, Bolton’s interpretation is completely devoid of angst. Phrasing is often mannered, Bolton embracing some of the worst traits of historically informed performance (HIP) style. Those chords at 0’58” that feel like massive walls of sound in performances led by Karajan and Mackerras, here go for nothing.

This is not a criticism of the playing itself; the Basel orchestra acquits itself admirably, giving Bolton exactly what he wants. But the music never conveys the tragedy Brahms intends. The secondary material at 3’38” is beautifully rendered, the melody sung with chaste beauty by strings and winds. But its emotional impact is blunted because the opening section was without fire and fury, taking away the emotional contrast between the opening and secondary material. Again, at 4’45” the exchanges between strings and brass are pleasant when they should be fearsome. Bolton seems unwilling, or unable, to inspire any sense of tragedy. That key ingredient is acutely realized in Manze’s performance with the Helsingborg Symphony Orchestra (CPO), and Chailly’s (perhaps overly driven) Gewandhaus recording (Decca). Blomstedt’s more recent performance with the same orchestra (Pentatone) is similarly driven but features more flexible phrasing, an even finer recording, and greater emotional clout.

Related Classical Music Reviews

- Brahms – Piano Concertos – András Schiff, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment

- Review: Brahms Complete Symphonies – Berlin staatskapelle, Daniel Barenboim

- Review: Brahms – Piano Concerto No. 1 – Moog, Deutsche Radio Philharmonie, Milton

The overture is discussed in such detail because Bolton’s interpretive approach is similar in the Concerto. At one point Brahms thought this music might be his first Symphony, so a successful realization of this Concerto’s symphonic dimension is key to a successful performance. But the opening orchestral introduction is woefully underpowered, especially when compared to Schiff’s recent recording with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment (ECM). Horns lack presence in the overall balance, and there is disappointing lack of forward momentum. While the timing of this movement is similar to other performances, it often feels sluggish. When the secondary material softly enters at 1’07”, it should feel like a much-needed respite from the onslaught of the opening – here it does not.

Melnikov’s first entrance is especially welcome then, because there is an immediate and perceptible increase in energy – the orchestral playing becomes more impassioned. Melnikov takes his time to shape each phrase, and at 5’42” his inward and fragile approach is a touching moment of self-reflection. With the winds’ entry it becomes an intimate dialogue between equals, a reminder that Melnikov is an experienced and sensitive chamber partner.

The piano’s sound is ideally caught, not overly spot-lit, the balance with the orchestra beautifully managed. According to the booklet, the instrument used is a Blüthner piano from 1859, restored by Christoph Kern – on paper the same piano Andras Schiff used in his recent ECM recording. At 11’49” Melnikov’s driving octaves inspire a fiercer, more vehement orchestral reprise of the opening material. While Schiff and Freire (Gewandhaus/Chailly/Decca) perhaps play this passage a touch more cleanly than Melnikov, the more immediate emotional urgency is ample compensation. At 14’45” the reading finally finds the power and emotional sweep of Brahm’s writing, but in the final minute there is another loss of forward momentum that weakens the closing chords.

The opening of the second movement needs more hushed expectancy (as it does with in the hands of Schiff and Zimerman (Berlin/Rattle/DG). Yet, once Melnikov enters the performance finds greater poetry. The subtle phrasing and chamber-music intimacy makes one feel emotionally invested. The final movement is mostly successful, in large part because the energy level is palpably higher. Melnikov tosses off the music’s difficult challenges with ease, and the orchestral playing has greater élan. (Was this movement perhaps recorded on a different day?) The music’s continual build-up of energy is well managed, leading into a highly satisfying ending, though greater thrills are heard and felt in the recordings by Schiff, Zimerman, and Moog (Deutsche Radio Philharmonie/Milton/Onyx).

The program ends with Cherubini’s “Eliza ou Le Voyage Overture.” Brigitte Francois-Sappey’s brief but informative liner notes explain that it was this overture that was played just before the concerto was premiered in Leipzig on January 27, 1859. The notes also discuss the dramatic flair of Cherubini’s music, an aspect heard only intermittently in this performance.

Melnikov and Bolton seem to have different interpretative conceptions of the Concerto. Having heard Schiff lead this work from the piano with such success, perhaps there might come a time when Melnikov does something similar.

Brahms:

Tragic Overture Op. 81

Piano Concerto No. 1 Op. 16

Cherubini:

Overture to Éliza, ou Le Voyage aux Glaciers du Mont Saint-Bernard

Alexander Melnikov – Piano

Sinfonieorchester Basel

Ivor Bolton – Conductor

Recommended Comparison

Read more classical music reviews or visit The Classic Review Amazon store

Follow Us and Comment:

Get our periodic classical music newsletter with our recent reviews, news and beginners guides.

We respect your privacy.